The occurrence

A limited-scope, fact-gathering investigation into this occurrence was conducted in order to produce this short summary report and allow for greater industry awareness of potential safety issues and possible safety actions.

What happened

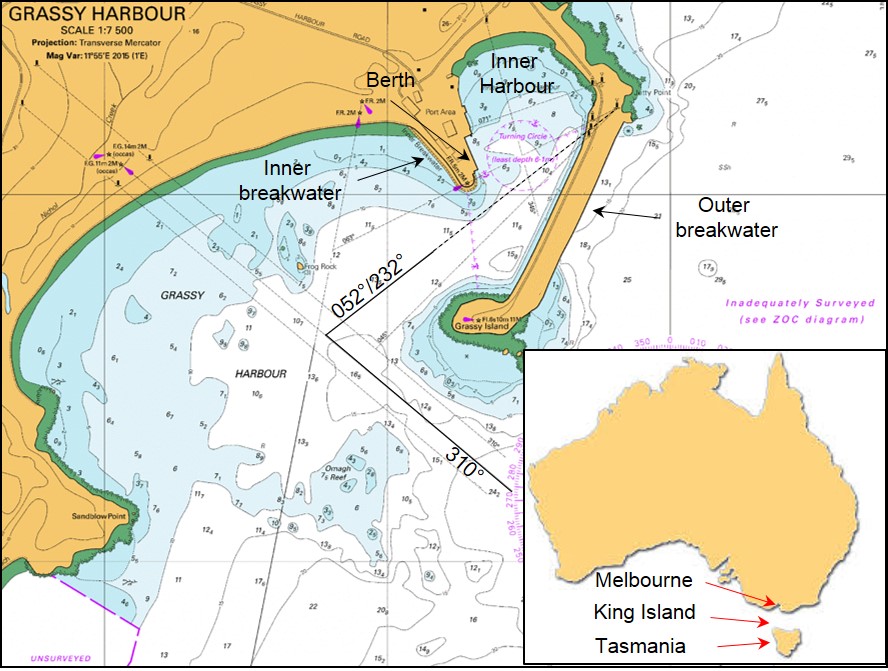

On 30 October morning, the 119 m general cargo ship Searoad Mersey (Cover) arrived off Grassy Harbour, King Island (Figure 1) from Melbourne, Victoria. The ship was operating a 7-day schedule between Melbourne, King Island and Devonport, Tasmania. At about 0700,[1] the ship’s master received a weather report for the harbour. The wind was from the north-west at 25 to 28 knots[2] as per the forecast.

Figure 1: Navigational chart Aus 178 showing Grassy Harbour

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office (annotated by ATSB)

At 0730, the ship approached Grassy Harbour’s outer breakwater at 12 knots. Shortly after, the master manoeuvred the ship into the outer harbour and started a starboard turn to bring the ship onto the inner lead beacons for the inner harbour. Once inside the inner harbour, the ship’s master swung the ship to port to berth the ship starboard side alongside the wharf.

By 0800, Searoad Mersey’s mooring lines were all fast. Shortly after, the ship’s stern ramp was lowered and cargo unloading started. Cargo operations continued throughout the day with several delays. As a consequence, the ship’s scheduled departure time of 1500 was delayed by an hour. The wind was from the west-northwest throughout the day at 27 to 33 knots.

At 1604, the ship’s main engines and bow thruster were on standby and ready for use. The master held a departure brief with the ship’s bridge team detailing the departure plan. The ship’s master and crew were very experienced and familiar with arrivals into and departures from Grassy Harbour. The standard brief detailed using the port engine ahead and full starboard rudder.

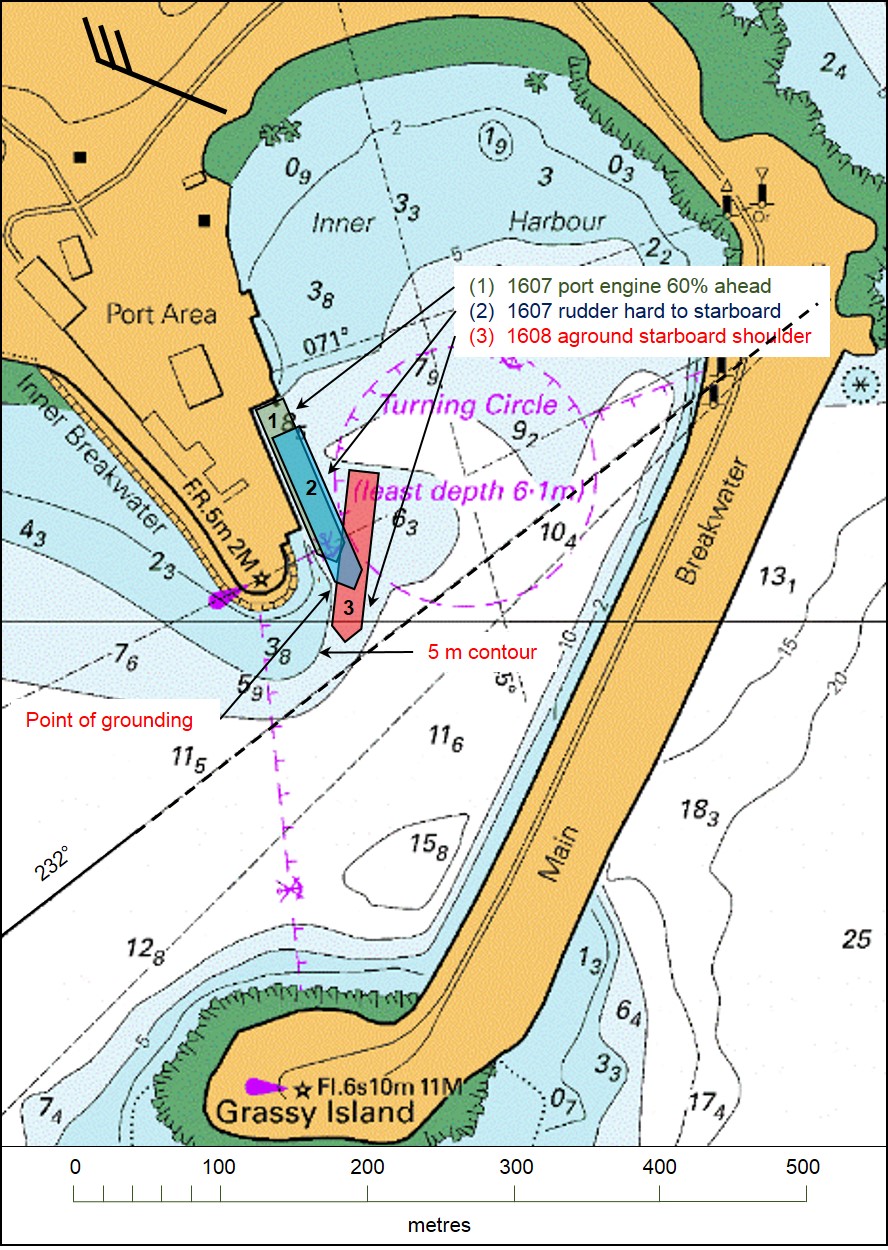

Figure 2: Searoad Mersey’s grounding in the Inner Harbour

South Australian Hydrographic Office (annotated by ATSB)

The wind was still from the west-northwest at 27 to 33 knots and the tide was ebbing with low water expected at 1853. The ship’s departure draughts were 5.1 m forward and 5.3 m aft. The master expected an under keel clearance of between 1 and 1.5 m for the departure.

At about 1605, the mooring lines were singled up forward and aft and by 1607, all mooring lines had been let go and recovered. The wind acting on Searoad Mersey’s starboard quarter[3] started to move the ship away the berth.

The ship’s heading[4] while alongside the berth was 155° and the next course was 232°, a 77° alteration to starboard. The master increased the port engine to 60 per cent ahead. The ship moved about 30 m ahead, parallel to the wharf, and the rudder was put hard over to starboard.

At 1608, the ship had moved ahead about 90 m and had started swinging to starboard. Shortly after, the ship grounded on the sandy bottom to the east of the inner breakwater (Figure 2).

The master stopped the port engine and put the bow thruster full to port. He then increased the starboard engine to 70 per cent ahead and the rudder hard to port. However, the ship’s starboard shoulder[5] remained grounded. Shortly after, the master unsuccessfully attempted to move the ship astern using both engines.

Searoad Mersey’s crew sounded the ship’s tanks to check for water ingress and started ballasting the ship’s port tanks to list the ship. However, the port list had no effect and the ship remained grounded forward with the stern swinging freely in deep water. The second mate then started pumping ballast from the fore peak tank to the aft peak tank, to reduce the draught forward.

At 1648, the master reported the grounding to the ship’s managers and the joint rescue coordination centre (JRCC) in Canberra. Shortly after, as the tide was still ebbing, he ordered the starboard anchor lowered to the sea bed.

At 1658, the main engines were stopped. Then, at 1700, the master felt Searoad Mersey roll slightly and immediately started the main engines. At 1705 with the main engines running astern, the ship started to move astern. The crew sounded the tanks again for any water ingress. The anchor was recovered and the rudder and engine tested. The master then manoeuvred the ship out of the inner harbour and continued the voyage to Devonport.

On 31 October, the ship’s flag State authority, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), attended the ship in Devonport. The ballast tanks were inspected and no damage was found.

On 3 November, Searoad Mersey underwent an underwater hull inspection in Melbourne. Minor paint damage near the starboard shoulder was found but there was no structural damage.

ATSB comment

Since the last hydrographic survey in 2015, it is probable that silting had occurred near the inner breakwater. It is likely that the reduction in water depth to the charted depths were the result of the predominant westerly winds blowing sand from the nearby beach into the channel together with the movement of sand within the harbour.

Safety message

Masters, harbour masters and others responsible for ships calling safely at ports need to assure themselves of the reliability of charted depths, particularly in some small, remote ports. A possible reduction in charted depths due to local conditions, reference to the charted zone of confidence diagrams and the date of the last hydrographic survey are among the factors that should be taken into account.

Read more about Maritime pilotage:

Navigation through confined waters under pilotage

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- All times referred to in this report are local time, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 11 hours.

- One knot, or one nautical mile per hour equals 1.852 kilometres per hour.

- The quarter is that part of the ship’s side between the stern and abaft of midships.

- All ship’s headings in this report are in degrees by gyro compass with negligible error.

- A shoulder is the area where a ship’s hull form changes from the bow shape to the parallel mid body.