What happened

On 5 September 2016, at about 0737 Central Standard Time (CST), a Cessna 441 aircraft, registered VH-NAX (NAX), departed from Adelaide Airport on a charter flight to Coorabie aircraft landing area (ALA), South Australia. On board were the pilot and nine passengers.

At about 30 NM from Coorabie, the pilot of NAX broadcast on the common traffic advisory frequency advising that they were inbound to the aerodrome. The pilot of another aircraft operated by the same company, that had landed some minutes earlier on runway 14 at Coorabie ALA, responded to the broadcast, advising the pilot of NAX to use runway 32 due to the downwards slope on runway 14 (Figure 1). The pilot of NAX had not previously operated into Coorabie ALA, but had studied prior to the flight the information provided by the operator (see Pilot hazard awareness below) with respect to any hazards associated with their landing. In addition, as the other company aircraft had landed safely, they elected to conduct a straight-in approach to runway 32. The pilot then positioned the aircraft on about a 10 NM final to runway 32.

Figure 1: Coorabie ALA facing south

Source: ALA operator

At about 0900, when the aircraft was on final approach to runway 32, the pilot reported that the aircraft decelerated suddenly (from about 120 to 110 kt). At the same time, there was a slight shudder of the right engine and a change in the sound of the propeller pitch. The pilot immediately increased the power to both engines and levelled the aircraft off. The pilot checked the engine instruments and the annunciator panel, and there were no abnormal indications.

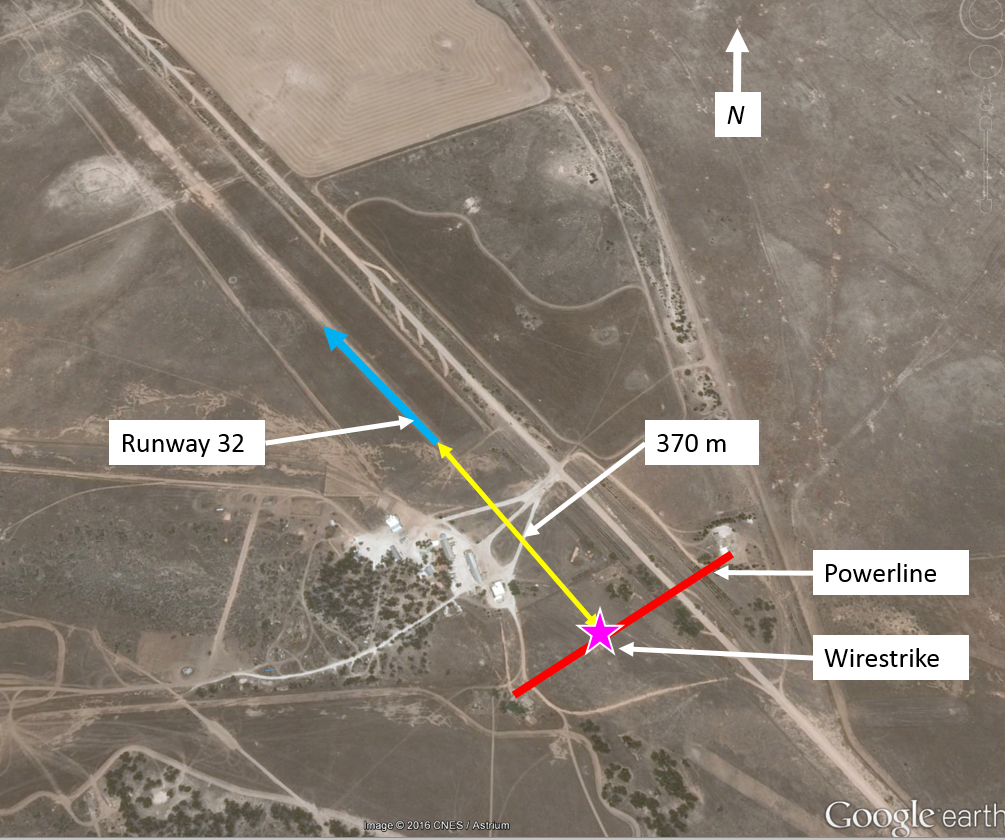

The pilot then conducted a go-around and a left circuit at about 1,100 ft above ground level. The aircraft subsequently landed on runway 32. While back-tracking, the pilot sighted a power pole on a hill beyond the runway 32 threshold (in the direction from which the aircraft had just approached). After shutting the aircraft down, the pilot noticed damage to the right propeller blades and suspected that the aircraft had struck a powerline (Figure 2). Witnesses on the ground confirmed that they had seen and heard the aircraft strike the powerline.

The pilot and passengers were not injured. The aircraft sustained minor damage.

Figure 2: Coorabie ALA showing the powerline 370 m from the threshold

Source: ALA operator

Pilot comments

The pilot of NAX had planned to overfly the runway, inspect the landing area and then join the circuit on the downwind leg for runway 14. The pilot commented that if they had overflown the airstrip prior to commencing the approach, they may still not have identified the powerline as the poles and wire were difficult to see. There was one pole near a house and the next pole was some distance away on terrain rising from the runway threshold. The company pilot who had landed before NAX did not sight the powerline during their strip inspection (overflying the runway).

The pilot further commented that if they had conducted a steeper approach they may not have struck the powerline.

Pilot hazard awareness

The pilot reported that they had not been alerted to the presence of the wire before operating at the aerodrome. The pilot had reviewed the company strip guide information for Coorabie ALA and photos of the runway provided by the aerodrome operator.

The information provided included a sketch of the runway and its direction (14/32), the latitude and longitude, length (900 m), width (25 m), elevation (75 ft) and under Special procedures: ‘Slight rise to NW end Small hill’.

Wire marking standards

The requirements for mapping and marking powerlines and their supporting structures were published in Australian Standard AS 3891.1, Part 1, Permanent marking of overhead cables and their supporting structures and AS 3891.2, Part 2, Marking of overhead cables for low level flying. The ALA was not used as described in Clause 3.2 of AS 3891.1 nor were the powerlines in an area involved in planned low-flying operations as described in AS 3891.2. The powerlines did not require marking in accordance with either Australian Standard.

Advisory material

The Civil Aviation Advisory Publication (CAAP) 92-1(1) Guidelines for aeroplane landing areas, provided guidance on how pilots may determine the suitability of an aeroplane landing area (ALA) such as the recommended obstacle clearance standards and suggested landing area markings. The CAAP defined an obstacle free area to mean ‘there should be no wires or any other form of obstacles above the approach and take-off areas, runway, runway strips, fly-over areas or water channels’. The minimum landing area physical characteristics recommended in the CAAP for aircraft (other than single-engine and centre-line thrust aeroplanes not exceeding 2,000 kg maximum take-off weight) for day operations is depicted in Figure 3. This shows the approach and take-off area should be clear of wires within 900 m of the runway ends above a 5 per cent (3°) slope.

Figure 3: Recommended landing area characteristics

Source: Civil Aviation Safety Authority

Powerline

The powerline was located about 370 m from the runway threshold and about 7.5 m above ground level. The powerline was below the recommended slope gradient of 5 per cent (Figure 3).

The operator of the ALA reported that they had spoken to a representative from the aircraft operator and advised them of the existence of the powerline prior to the flight. The ALA operator had identified the powerline as a hazard and reported that they had requested the infrastructure provider to fit markers to the powerline about 12 months prior to the incident.

The power insfrastructure provider advised the ATSB that the ALA operator had enquired with the then distribution licensees about the fitting of markers to the powerline in 2012 and 2015. In 2012, the distribution licensee investigated and determined that the span of the powerline was too long to take the additional load of the markers. In 2015, the request for the markers was raised again by the ALA operator in conjunction with a request for a quote on a transformer upgrade. There was no follow-up with the provider about these requests.

Runway illusions

The profile of Coorabie ALA runway 32 and the approach area of 900 m (based on the recommended dimensions specified in Figure 3), obtained from Google earth, is depicted in Figure 4. The cleared area commencing from the runway threshold was about 1,170 m in length. Along that length, the profile rose from 9 m (30 ft) to 22 m (72 ft) elevation at the nominated runway length of 900 m, with higher ground rising to about 29 m (90 ft) beyond 900 m. The information provided to the operator by the ALA operator was that the runway length was 900 m, suggesting that the rising terrain beyond that point was not part of the runway. The stated runway elevation was 75 ft (23 m).

As can be seen in Figure 4, the terrain at the powerline was about the same height as the runway 32 threshold, with a dip in between. The glide path from a powerline 7.5 m above the terrain to the runway threshold was about 1°. A normal approach path is about 3°.

Runway slope is one environmental condition that can affect a pilot’s perception of the aircraft’s position relative to a normal approach profile. Flight Safety Foundation Approach and landing accident reduction tool kit briefing note 5.3 – Visual illusions stated that an uphill slope creates the illusion of being too high. That illusion may induce the pilot to ‘correct’ the approach resulting in a lower flight path, or may prevent the pilot from detecting when the aircraft is too low during the approach.

The briefing note advises that to reduce the effects of visual illusions, flight crews should assess approach hazards and be trained to recognise and understand the factors and conditions that cause visual illusions.

Figure 4: Coorabie ALA runway 32 and 900 m approach area profile

Source: Google earth annotated by ATSB

ATSB comment

It is essential for pilots to be aware of hazards prior to operating into an aerodrome. The location of known hazards and obstacles such as powerlines should be included in aerodrome information that is provided to pilots and aircraft operators who are permitted to operate at the airfield. As runway slope can result in visual illusions that may affect a pilot’s judgement of the approach profile, runway slope information should also be included in operational information.

CAAP 166-1(3): Operations in the vicinity of non-controlled aerodromes stated that straight-in visual approaches are not a recommended standard procedure. They can be conducted provided certain conditions are met, including that pilots must be able to assure themselves of the aerodrome’s serviceability and that hazards have been identified.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following safety action in response to this occurrence.

Powerline owner

Following the incident (at the time of repairing the wire), the infrastructure provider marked the wire with three round orange markers (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Powerline with orange markers

Source: ALA operator

Aircraft operator

As a result of this occurrence, the aircraft operator has advised the ATSB that they are taking the following safety actions:

Notice to operational crew

The company issued the following directives in a notice to operational crew:

- Operations to new ALAs require specific chief pilot approval.

- ALAs that have not been used by company aircraft for more than 12 months are treated as new.

- All operations to ALAs require an overhead join to check the runway.

- Straight-in approaches to ALAs are not permitted.

Safety message

Research conducted by the ATSB found that 166 aircraft wirestrikes were reported to the ATSB between July 2003 and mid-June 2011 and another 101 occurred and were unreported but identified by electricity distribution and transmission companies. The majority of wirestrike occurrences were associated with aerial agriculture operations, however, 22 occurrences (8 per cent) involved private operations. Further information is in the research report, Under reporting of aviation wirestrikes.

The ability of pilots to detect powerlines depends on the physical characteristics of the powerline such as the spacing of power poles, the orientation of the wire, and the effect of weather conditions, especially visibility.

Depending on the environmental conditions, powerlines may not be contrasted against the surrounding environment. Often the wires will blend into the background vegetation and cannot be recognised. In addition, the wire itself can be beyond the resolving power of the eye: that is, the size of the wire and limitations of the eye can mean that it is actually impossible to see the wire. As such, pilots are taught to use additional cues to identify powerlines, such as the associated clearings or easements in trees or fields that can underlie the powerline, or the power poles and buildings to which the powerlines may connect.

Risks associated with operations to private airstrips can be mitigated by ALA owners assessing their airstrips against the guidance in CAAP 92-1(1) Guidelines for aeroplane landing areas. Such risk assessments would benefit from giving consideration to first time users of the ALA.

ATSB research report An overview of spatial disorientation as a factor in aviation accidents and incidents stated that ‘runway illusions can be mitigated against by pilots being aware of the characteristics of their destination airfield in advance, and by being aware of the potential for such illusions to occur’.

Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 55

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |