What happened

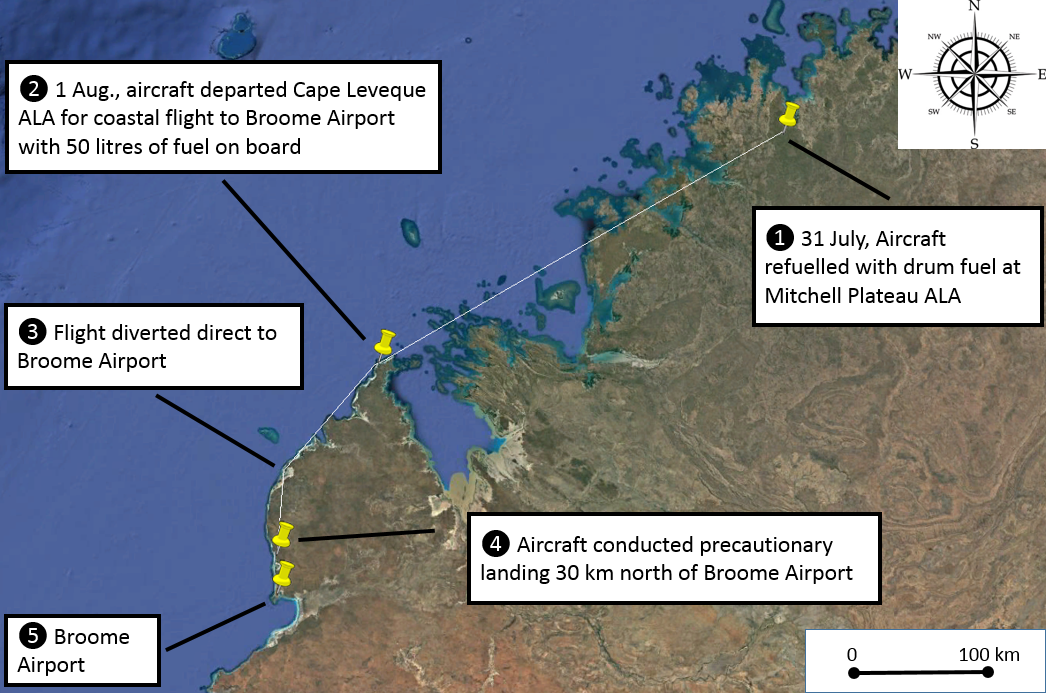

On 1 August 2016, at about 0830 Western Standard Time (WST), a Cessna 172 aircraft, registered VH-WKB (WKB), departed from Cape Leveque Aircraft Landing Area (ALA), Western Australia (WA). The pilot (owner) and one passenger were on board the private flight.

Prior to departure, the pilot had checked the amount of fuel in the aircraft’s fuel tanks with a dipstick and estimated there was about 50 litres of fuel remaining. The pilot planned a one hour coastal sightseeing flight to Broome, using a five knot headwind component, at a fuel flow of 35 litres per hour.

Shortly after departure, the pilot noted the headwind component had increased from five knots to about 25 knots. About 45 minutes into the flight, the fuel gauges were indicating lower than the pilot had anticipated, so they initiated a climb to a higher altitude in an attempt to improve their flight range. About one hour and five minutes into the flight, the pilot heard the engine make a ‘bit of a cough’ and noticed the fuel gauges were indicating empty. Considering that their direct track to Broome Airport would require them to fly over water and a residential area, the pilot elected to conduct a precautionary landing.

The pilot identified a clear section of straight road ahead, broadcast a MAYDAY[1] call and landed the aircraft on the Manari road, about 30 kilometres north of Broome airport (Figure 1). The aircraft had been flying for about one hour and 10 minutes. There were no injuries and the aircraft was not damaged.

Following the landing, the pilot confirmed with Broome Air Traffic Control that they landed safely and cancelled their MAYDAY. Aviation fuel was transported by road, to where WKB had landed and it was refuelled. Two vehicles blocked a section of the road to allow WKB to depart for Broome and the aircraft landed at Broome without further incident.

Weather planning

The pilot checked the area forecast and the Broome airport aerodrome forecast (TAF)[2] before departure and elected to use the TAF wind of five knots because they planned to fly at about 500 feet. On arrival at Broome Airport, the pilot noted the wind speed on the Broome TAF had increased to 24 knots with gusts to 38 knots.

Figure 1: VH-WBK flight with key events

Source: Google earth, annotated by ATSB

Fuel consumption

In March 2015, the pilot flew the aircraft from Moorabbin Airport, Victoria, to Kununurra Airport, WA, and calculated the average fuel flow was 32 litres per hour. In June 2016, a periodic inspection was conducted, which included a calibration check of the fuel gauges and dipstick.

The day prior to the incident flight, the pilot flew the aircraft to Mitchell Plateau ALA, where it was refuelled with aviation fuel from a drum, and then onward to Cape Leveque (Figure 1). The use of fuel from a drum at Mitchell Plateau precluded an accurate fuel flow check by the pilot and there was no fuel stock available at Cape Leveque during their overnight stay.

Subsequent to the incident flight the pilot calculated the fuel flow had increased from 32 litres per hour to 37 litres per hour.

Safety message

This serious incident highlights how several factors, which on their own were not critical, combined on the day to result in a critical situation for the pilot. The fixed fuel reserve on board at the time of departure was less than the recommended 45 minutes for piston engine aircraft flights, as published in Civil Aviation Advisory Publication 234-1(1) – Guidelines for aircraft fuel requirements. Shortly after departure the headwind component increased and unknown to the pilot, the fuel consumption was greater than planned.

The pilot commented that they were not in a rush and probably too relaxed in their approach to the flight. Consequently, the effect of the change in wind speed on fuel reserves was not given the priority that it required. They also highlighted the importance of aircraft owners confirming fuel consumption after a periodic inspection is conducted.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 53

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________