What happened

On 11 May 2016, an Airbus A320-232, registered VH-VGF (VGF) and operated by Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd was taking off on runway 27 at Melbourne Airport, Victoria. The flight crew consisted of a training captain in the left seat, a cadet pilot in the right seat and a safety pilot, who was also the first officer, in the jump-seat. This was the cadet pilot’s first take-off as pilot flying. During rotation, the tail of the aircraft contacted the runway surface.

After take-off, the cadet pilot realised that the pitch rate during rotation was higher than normal and discussed this with the captain. During the climb, the cabin crew discussed hearing an unusual noise during the take-off rotation with the captain. Due to the higher-than-normal rotation rate and the noise heard by the cabin crew, the captain elected to stop the climb and return to Melbourne. The first officer swapped seats with the cadet pilot and the aircraft landed uneventfully on runway 27.

What the ATSB found

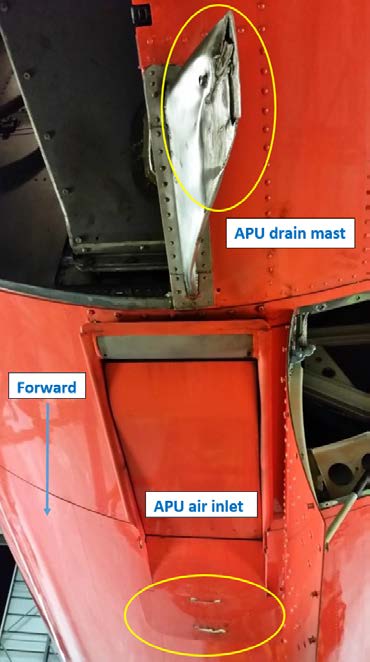

The ATSB found that during rotation, the cadet pilot applied a larger than normal sidestick pitch input resulting in a higher-than-normal pitch rate. The tail of the aircraft contacted the runway surface resulting in damage to the auxiliary power unit (APU) diverter and APU drain mast. While airborne, the crew did not specifically advise air traffic control (ATC) of the possibility that a tail strike had occurred during take-off.

What's been done as a result

The cadet pilot undertook additional training and assessment before returning to flight duties. Soon after the event, the operator circulated a newsletter to their A320 flight crew highlighting the need to inform ATC of a suspected tail strike or any potential failure resulting in damage/debris.

Safety message

Good communication from the cabin crew alerted the flight crew that a tail strike may have occurred. The climb was stopped and a timely decision to return to Melbourne was taken which minimised the potential risk from damage caused by a tail strike.

It is important to notify ATC of a possible tail strike as soon as operationally suitable. When a potential tail strike has been reported, ATC restricts operations on the affected runway and arranges that a runway inspection is carried out to identify any runway damage or aircraft debris.

At 1449 Eastern Standard Time on 11 May 2016, an Airbus A320-232, registered VH-VGF (VGF) and operated by Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd was taking off on runway 27 at Melbourne Airport, Victoria for a planned flight to Hobart, Tasmania. The flight crew consisted of a training captain in the left seat, a cadet pilot in the right seat and a safety pilot, who was also the first officer (FO), in the jump-seat. This was the first take-off as pilot flying[1] (PF) for the cadet pilot.

After take-off, the cadet pilot realised that the pitch rate during rotation was higher than normal and discussed this with the captain. Later, during the climb, the cabin crew alerted the captain to unusual noises during rotation. As a result, the captain elected to stop the climb and return to Melbourne. The first officer also swapped seats with the cadet pilot.

The aircraft descended and landed uneventfully on runway 27. During the flight, no faults were annunciated to the crew.

After landing, engineers inspected the aircraft. Damage to the auxiliary power unit (APU) diverter (air inlet) and APU drain mast was evident. This damage was consistent with the aircraft tail contacting the runway surface during rotation.

Flight crew information

The cadet pilot had completed training leading to a Commercial Pilot’s Licence (CPL) and a multi-engine command instrument rating and had completed the theory examinations for an Air Transport Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence (ATPL). An A320 type rating was gained after ground school and simulator sessions were successfully completed. The simulator component consisted of ten 2-hour sessions.

The flight was scheduled as a training flight with the cadet pilot conducting his fifth sector of line training and the first sector of the current shift. There was also an FO in the jump seat acting as a safety pilot. The four previous sectors had been flown with the cadet pilot as pilot monitoring (PM). This was the first flight for the cadet pilot as PF.

The training captain was suitably qualified and experienced.

Aircraft information

Pitch control

The A320 is a ‘fly-by-wire’ aircraft, that is, there was no direct mechanical link between most of the flight crew’s controls and the flight control surfaces. Flight control computers send movement commands via electrical signals to hydraulic actuators that are connected to the control surfaces.

The controls include the sidestick controllers (or sidesticks) to manoeuvre the aircraft in pitch and roll. During manual flight, such as take-off, the flight crew make pitch control inputs using their sidesticks. Both the captain’s and first officer’s sidesticks move independently and there is no mechanical link between them. The range of movement of the sidestick in pitch is ± 16°.

Rotation technique

The following extracts are from the operator’s Flight Crew Training Manual:

On a normal take-off, to counteract the pitch up moment during thrust application, the PF should apply half forward (full forward in cross wind case) sidestick at the start of the take-off roll until reaching 80 kts. At this point, the input should be gradually reduced to be zero by 100 kts.

During the take-off roll and the rotation, the pilot flying scans rapidly the outside references and the primary flight display (PFD). Until airborne, or at least until visual cues are lost, this scanning depends on visibility conditions (the better the visibility, the higher the priority given to outside references). Once airborne, the PF must then control the pitch attitude on the PFD using the flight director (FD) bars in speed reference system (SRS)[2] mode which is then valid.

Initiate the rotation with a smooth positive backward sidestick input (typically 1/3 to 1/2 backstick). Avoid aggressive and sharp inputs. The initial rotation rate is about 3 deg/sec. If the established pitch rate is not satisfactory, the pilot must make smooth corrections on the stick. He must avoid rapid and large corrections, which cause sharp reaction in pitch from the aircraft.

Pitch limitation

The manufacturer advised that, with the main gear oleo[3] fully compressed and wings level, the pitch attitude that will result in ground contact for the A320 is 11.7°. With the main gear oleo fully extended, the pitch attitude that will result in ground contact is 13.5°.

Take-off configuration

Data from the flight recorders showed:

- gross weight was 64.7 tonnes

- take-off flap setting was Config 1+F[4] (slats/flaps 18°/10°)

- trim setting was +1.4 units consistent with a centre of gravity (CG) of 34.4 per cent

- FLEX[5] temp used was 64 °C

- V1/VR[6] speeds used were 137/140 kt

The flap setting, trim setting and take-off speeds used agreed with those calculated by the aircraft manufacturer.

Flight recorders

The ATSB downloaded and analysed both the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and the flight data recorder (FDR).

CVR

Crew interviews and CVR information showed that:

- All the required briefings and checklists were performed.

- The PM noticed approximately 6 medium-sized birds flying from left to right as the aircraft was reaching V1.

- The calls of ‘V1’ and ‘rotate’ were made at the appropriate time.

- The rotation was significantly faster than usual. The rotation was stopped at approximately +16° and a normal climb was flown with a standard acceleration, and cleanup was conducted normally.

- There were no abnormal indications, and the pilots didn’t hear or feel anything unusual during the climb.

- During climb, the cabin manager (CM) called the flight deck and informed the captain that the two cabin crew seated in the rear of the cabin had felt that the take-off was different from usual and thought something had moved or made a noise/vibration.

- The captain immediately called the rear galley to gather more information first hand. The cabin crew advised that they had felt that the aircraft tilted more rapidly or to a different angle than was usual. They also advised that they heard and felt some kind of movement in the rear of the aircraft. The cabin crew thought the noise was something in the cargo hold and there was a sliding or thump type of noise/vibration in the underfloor or rear galley area. The cabin crew also said that it may have been the sound of the aircraft tail possibly contacting the runway.

- With this information and the knowledge of the higher rotation rate at take-off, the captain decided that the safest course of action would be to cease the climb and to return to Melbourne for a precautionary engineering inspection. The climb was stopped while the aircraft systems were checked but there were no abnormal indications. The captain took control and was PF for the approach and landing at Melbourne.

- The captain advised air traffic control (ATC) that the flight would need to return to Melbourne due to an ‘engineering issue’ and that ‘ops were normal’. The cadet pilot and safety pilot changed seats and the safety pilot became the PM for the return to Melbourne.

- After landing, an engineering inspection confirmed that a tail strike had occurred. The captain then advised ATC that a tail strike had occurred.

FDR

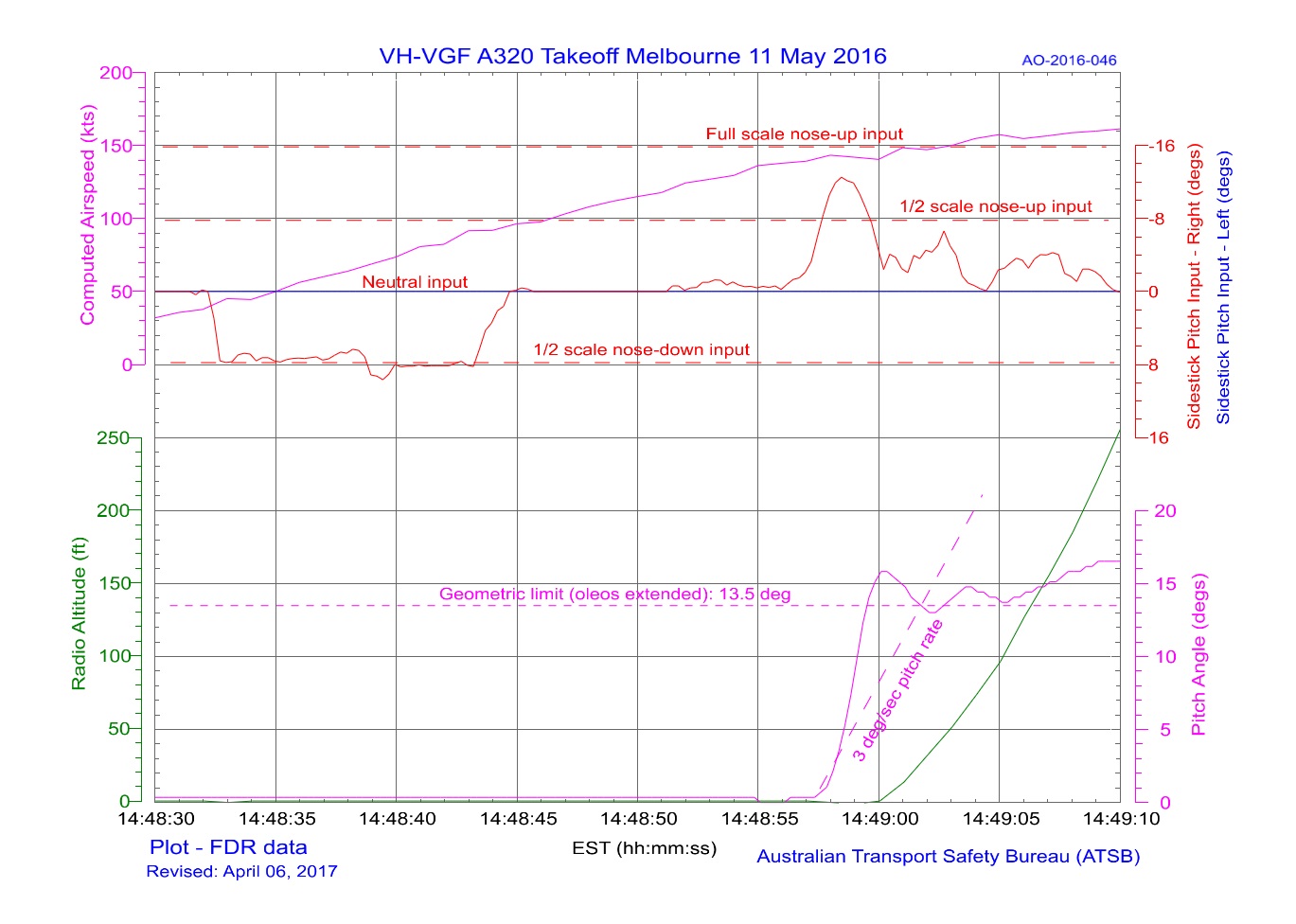

Key parameters from the FDR were analysed and are shown in Figure 1.

The aircraft taxied onto runway 27 and the take-off commenced at 1448. The sidestick data shows that the pilot in the right seat (cadet) was the PF. At approximately 40 kt, a nose-down sidestick input was made and this input remained until the aircraft had accelerated to 100 kt. The sidestick pitch input was then neutral until approximately 140 kt when a nose-up input commenced. The nose-up input reached a maximum value of 12.5° or 78 per cent of a full-scale input. The aircraft rotated with a pitch rate of about 9 deg/sec reaching a maximum pitch attitude of 16°. The sidestick input was then reduced and the aircraft’s pitch attitude correspondingly reduced.

The aircraft climbed and levelled at FL226 at 1458. The aircraft returned to Melbourne and landed on runway 27 at 1523. The pilot in the left seat was the PF for the landing.

Figure 1: FDR plot of key parameters

Weight and balance

There was no evidence of any anomalies with the aircraft weight and balance. The recorded trim setting for the horizontal stabiliser (+1.4 units nose-down) was in accordance with the centre of gravity documented on the loadsheet. Post-flight checks did not reveal any evidence of cargo load-shifting.

Runway inspection

During take-off, as the aircraft became airborne, the captain and safety pilot observed that the aircraft had flown through ‘about 6 birds or so’. The cadet pilot reported not noticing the birds.

After take-off, the captain advised ATC about the birds but ‘didn’t think that they had hit any’. Later, ATC advised the crew that nothing had been found on the runway. While airborne, the captain did not advise ATC of a possible tail strike as he considered that it was unlikely to have occurred.

After landing, an engineering inspection confirmed that a tail strike had occurred, and the captain then passed on that information to ATC.

Airservices Australia advised that when a bird strike is reported to ATC, a runway inspection is initiated which specifically looks for bird carcasses or any evidence that a bird strike occurred. Arriving and departing aircraft are given the option of continuing their approach or departure, or delaying until the inspection is complete.

When a potential tail strike has been reported, ATC restricts operations on the affected runway, and arranges for a runway inspection to be carried out which looks for runway damage and aircraft debris.

Aircraft inspection

After landing, engineers inspected the tail of the aircraft (Figure 2). Damage to the APU diverter (air inlet) and APU drain mast was evident (Figure 3). This damage was consistent with the aircraft tail contacting the runway surface.

Figure 2: General location of damage

Source: Victor Pody annotated by ATSB

Source: Victor Pody annotated by ATSB

Figure 3: Damage to aircraft tail section (circled). Note: access doors are open for inspection

Source: Operator annotated by ATSB

Weather

Weather information was obtained from the Bureau of Meteorology. Visibility was 10 km or more with a few clouds at 3,000 ft. The automatic terminal information service (ATIS) wind was 300/16[7] with a maximum crosswind of 16 kt.

The operator has a crosswind limitation of 10 kt for cadet pilots. The captain observed the crosswind component using the windsock, while lining up for take-off, and assessed it as a maximum of 10 kt.

There were four anemometers at Melbourne airport which log minimum, maximum and average wind information over a one-minute period. The closest anemometer to the point of rotation was the northern anemometer. The one-minute values were:

- 0448 UTC average 333/10[8] (maximum 15 kt)

- 0449 UTC average 334/11 (maximum 14 kt).

For runway 27, a wind of 334 degrees at 11 kt equated to a crosswind from the right of 10 kt.

Other events

The ATSB occurrence database was searched for ground strike events for all aircraft types from 1980 onwards. Fifty-one events were found, 22 occurring on take-off, 26 on landing and the phase of flight was unknown for 3 occurrences. The aircraft type represented most frequently was the B767-300 (13 occurrences) noting that the B767-300 is equipped with a tail skid. There were no other reported occurrences involving an A320 and none involving an A321.

__________

- Pilot flying (PF) and pilot monitoring (PM) are procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances; such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and aircraft flight path.

- SRS is a vertical mode that provides speed guidance during takeoff or go around.

- An oleo strut is a shock absorber used on the landing gear of most large aircraft. The compressed gas/oil design cushions the impact of landing and damps out vertical oscillations.

- A higher flap setting provides a greater tail strike margin.

- An assumed temperature to allow a reduced thrust takeoff, which reduces the amount of thrust the engines deliver, thereby reducing wear on the engines.

- V speeds are used for takeoff as follows:V1: the critical engine failure speed or decision speed. Engine failure below this speed shall result in a rejected takeoff; above this speed the take-off run should be continued.VR: the speed at which the aircraft rotation is initiated by the pilot.V2: the minimum speed at which a transport category aircraft complies with those handling criteria associated with climb, following an engine failure. It is the take-off safety speed and is normally obtained by factoring the minimum control (airborne) speed to provide a safe margin.

- Wind direction in °Magnetic / wind speed in kt.

- Wind direction in °True / wind speed in kt.

Introduction

The possibility of a tail strike led the captain to decide to return the aircraft to Melbourne for a precautionary engineering inspection. This analysis will examine the actions of the flight crew and any operational issues that had the potential to affect the flight or other flights.

Rotation

The rotation was initiated at the correct speed and there was no evidence of any anomalies with the aircraft weight and balance, trim setting or any aircraft system.

During rotation, the cadet pilot applied a larger than normal pitch input (3/4 backstick versus the recommended 1/2 to 2/3 of backstick travel) resulting in an excessive pitch rate during rotation (9 deg/sec versus a target of 3 deg/sec).

Following the incident, the cadet pilot undertook additional training and assessment before returning to flight duties.

Risk controls

Pitch monitoring

The independent nature of the sidesticks meant that the training captain could not directly monitor the cadet pilot’s sidestick input. The resultant pitch rate that occurred during the take-off could be monitored and was observed by the captain as being faster than normal. Despite this, the entire rotation period was brief and there was little time for the Captain to respond to an inappropriate pitch input.

Flight data analysis program

The operator routinely monitors flight data through a flight data analysis program. Pitch attitude and pitch rates recorded during rotation are monitored to identify exceedances and operational trends. If an adverse trend is detected then corrective action can be taken (for example through a change to the training syllabus or advice to crew through a newsletter) and the effects of the change(s) monitored.

Runway inspection

Debris poses a hazard to aircraft taking off and landing and ATC should be advised as soon as operationally suitable if a tail strike is suspected. When a possible tail strike has been reported, ATC restricts operations on the affected runway and arranges for a runway inspection to be carried out which looks for runway damage as well as aircraft debris. Metallic debris poses a particular hazard to aircraft tyres.

As well, if debris is identified then this would confirm to the crew while airborne that a tail strike had occurred.

In this case, the pilot advised ATC that they were returning due to an engineering issue, but did not mention that they may have had a tail strike during take-off.

Following this incident, the operator circulated a newsletter to their A320 flight crew highlighting the need to inform ATC of a suspected tail strike or any failure resulting in damage/debris.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the tail strike during take-off involving Airbus A320 VH-VGF at Melbourne Airport, Victoria on 11 May 2016. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Contributing factor

The cadet pilot applied a larger than normal sidestick pitch input to initiate rotation. This resulted in a high rotation rate during the take-off and the aircraft’s tail contacted the runway.

Other factor

The potential tail strike was not adequately communicated to Melbourne air traffic control. This delayed checking the runway for aircraft debris.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- crew interviews

- operator’s report

- maintenance documents

- Bureau of Meteorology weather reports and observations

- flight recorders (FDR and CVR).

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to Jetstar, the captain, the cadet pilot, Airbus, Airservices Australia and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Submissions were received from the captain, Airservices Australia and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |