What happened

On 13 April 2016, an instructor and student of a Jabiru J170-D aeroplane, registered 24-7750 (7750), conducted a local training flight from Bathurst Airport, New South Wales. At about 1442 Eastern Standard Time (EST), as they were returning to Bathurst, the instructor broadcast on the Bathurst common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) that they were inbound from the south-west, and added that they were estimating arrival in the circuit at 1446. As they subsequently arrived in the circuit, the instructor broadcast that they were joining the circuit on an early downwind for runway 17, for a full-stop landing.

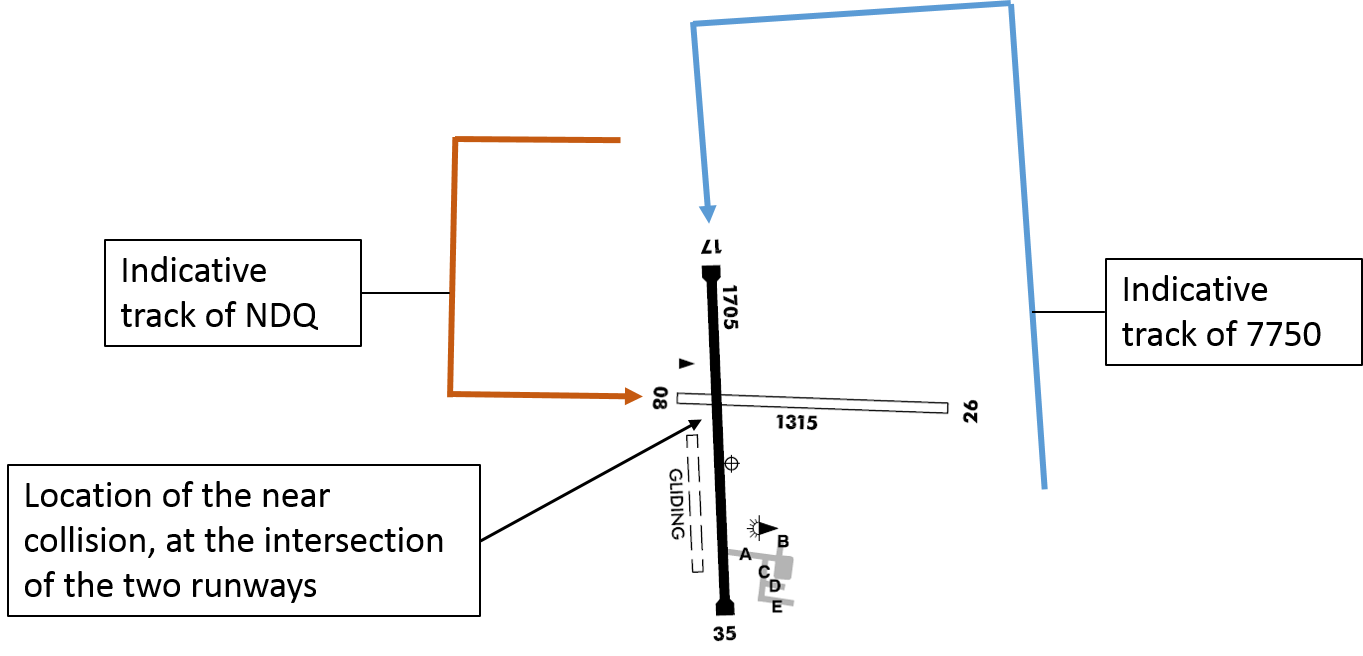

The wind was from the east-south-east. Powered aircraft were operating on runway 17 and gliders (and towing aircraft) were operating on runway 08. Bathurst aerodrome elevation is 2,435 ft above mean sea level (AMSL) (Figure 1).

About a minute after broadcasting their arrival in the circuit, the pilot of 7750 asked Glider Ground[1] how many gliders were in the air. Glider Ground advised that there were ‘two gliders, NGH and NDQ, just thermalling,[2] at 4,000 ft off the threshold of runway 26.’ The pilot of 7750 confirmed sighting two gliders.

Meanwhile, a student pilot of a Glaser-Dirks DG-1000S glider, registered VH-NDQ (NDQ) was conducting a solo flight at Bathurst. The student had been briefed prior to the flight to make a downwind call, stay close to the runway in use by the gliders, and to keep a good lookout. At about 1449, about 90 seconds after the pilot of 7750 had communicated with Glider Ground regarding glider traffic in the air, the pilot of NDQ broadcast on the Bathurst CTAF that they were on left downwind for runway 08.

Immediately following the downwind call by the pilot of NDQ, the pilot of 7750 broadcast that they were on left base for runway 17, and soon after, broadcast that they were on final approach to runway 17 for a full stop landing. The pilot of NDQ reported hearing both those broadcasts, but did not make any broadcasts or directed radio calls in response.

After 7750 touched down on runway 17, about 100 m before the intersection with runway 08, the pilot sighted a glider (NDQ) on short final for runway 08, at an estimated 100 ft above ground level. The pilot assessed that they did not have sufficient time to stop before the intersection of runway 08, so applied full power to cross runway 08 as quickly as possible.

When at about 500 ft above ground level and on final approach to runway 08, the pilot of NDQ sighted 7750 their 10 o’clock[3] position at about the same altitude. As 7750 landed, the pilot of NDQ assessed that there was the potential for a collision, closed the glider’s airbrakes[4] and initiated a climb to pass over 7750. As the glider passed over 7750 near the intersection of the two runways, the pilot of NDQ heard the aircraft’s engine increase power. The glider then landed ahead on runway 08 (Figure 1).

The instructor in 7750 lost sight of NDQ as it passed overhead. As 7750 accelerated with a high power setting, the instructor elected to continue the take-off. The pilot of 7750 then conducted a circuit before landing safely.

Figure 1: Layout of Bathurst aerodrome showing indicative tracks of 7750 and NDQ

Source: Airservices Australia – annotated by ATSB

Source: Airservices Australia – annotated by ATSB

Pilot comments - Pilot of 24-7750

The pilot of 7750 commented that the circuit was very busy at the time of the incident. They were maintaining a good lookout and listening intently to the CTAF for positional information from the gliders, noting that gliders would have ‘right of way’ over powered aircraft. During final approach to runway 17, the instructor was communicating with the student in 7750 for teaching purposes.

The pilot also commented that they now discuss operational intentions with the glider operator at the commencement of each day’s operations.

Safety message

Simultaneous operations on crossing runways can be problematic, particularly where the volume of traffic is high and where the nature of the potentially conflicting operations are dissimilar (such as powered flight and gliding operations). Organisations responsible for the coordination and conduct of such activities are encouraged to carefully assess and manage the risks involved. This is particularly important when operations are likely to involve instructional flights and relatively inexperienced pilots, where workload and the potential for pilot distraction may be elevated.

This incident highlights the importance of effective communication. The primary purpose of communications on the CTAF is to ensure the maintenance of appropriate separation through mutual understanding by pilots of each other’s position and intentions. Where a pilot identifies a risk of collision, that pilot should alert others as soon as possible to allow a coordinated and effective response.

Civil Aviation Advisory Publication 166-1(3) stated that ‘whenever pilots determine that there is a potential for traffic conflict, they should make radio broadcasts as necessary to avoid the risk of a collision’.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 51

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- A duty gliding instructor operates Glider Ground on the CTAF when there are a large number of low-hour solo students gliding. The duty instructor maintains an oversight of the gliding operations, and provides information on glider positions where required to enhance situational awareness for the pilots of gliders and other aircraft.

- Thermalling refers to the use of a column of rising air by gliders as a source of energy.

- The clock code is used to denote the direction of an aircraft or surface feature relative to the current heading of the observer’s aircraft, expressed in terms of position on an analogue clock face. Twelve o’clock is ahead while an aircraft observed abeam to the left would be said to be at 9 o’clock.

- Closing the airbrakes improves the aerodynamic efficiency of the glider.