On 8 September 2004, the owner/pilot of a Robinson Helicopter Company R44 Raven II helicopter, registered VH-JWX, conducted a private flight under the visual flight rules (VFR) from Coffs Harbour, NSW to Eurella Station, Qld. The flight included a landing at Roma, Qld where the pilot refuelled the helicopter with 180 L of Avgas from the bulk underground fuel storage supply. The pilot then continued to Eurella Station, located approximately 54 km west of Roma, arriving at 1705 Eastern Standard Time. The pilot shut down the engine and the property owner boarded the helicopter for a pre-arranged local flight. The pilot made several attempts to start the engine, during which it backfired a few times. Once started, the engine seemed to function normally.

FACTUAL INFORMATION

History of the flight

On 8 September 2004, the owner/pilot of a Robinson Helicopter Company R44 Raven II helicopter, registered VH-JWX, conducted a private flight under the visual flight rules (VFR) from Coffs Harbour, NSW to Eurella Station, Qld. The flight included a landing at Roma, Qld where the pilot refuelled the helicopter with 180 L of Avgas from the bulk underground fuel storage supply.1 The pilot then continued to Eurella Station, located approximately 54 km west of Roma, arriving at 1705 Eastern Standard Time. The pilot shut down the engine and the property owner boarded the helicopter for a pre-arranged local flight. The pilot made several attempts to start the engine, during which it backfired a few times. Once started, the engine seemed to function normally.

The helicopter departed the homestead at 1725 in a northerly direction. A person on an adjoining property about 7 km north of Eurella homestead saw the helicopter operating to the east late in the afternoon. He reported that the helicopter conducted a number of take-offs and landings in what appeared to be the same general area over a period of about 30 minutes. He saw the helicopter depart in a southerly direction at about 1830.

The next reported sighting was by a person at Eurella homestead who, in poor light conditions, saw what appeared to be the helicopter's landing light to the north of the homestead. The light moved toward the west of the homestead. Soon after, that person again saw the light to the west and expected the helicopter to land at the homestead within a few minutes. However, she became concerned when the helicopter did not arrive and telephoned an employee of the property owner to report her concern. The employee contacted the Australian Search and Rescue organisation (AusSAR) and search action was initiated. The helicopter was located the following morning in open, rolling country, 3 km west of Eurella homestead. The two occupants were fatally injured, and the helicopter was destroyed.

Search and rescue

AusSAR reported that it was notified at 1947 that the helicopter was overdue. Weather conditions were unsuitable for an air search, but a surface search was initiated. AusSAR advised that no ELT signal was received on 8 September by satellite or by aircraft at high altitude passing within 130 km of Eurella Station. An ELT signal was detected on two satellite passes early on the morning of 9 September. The signals were identified as originating from separate locations; one approximately 22 km to the south-west, and the other approximately 22 km to the south-east, of Eurella Station. However, those signals were not merged by the satellites as coming from the same source, so they were of little assistance in the search. Local aircraft were tasked to begin a search at daylight on 9 September and the wreckage was located at 0708 by the crew of a search aircraft. Accident site information

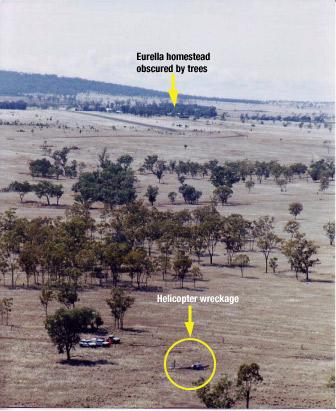

The accident site elevation was about 30 m below the ground elevation at the homestead. The homestead was not visible from the accident site.

Figure 1: Aerial view of the accident site

GPS track information

The helicopter was fitted with a fixed global positioning system (GPS) receiver, and also a handheld GPS receiver mounted in a cradle on the instrument panel. The fixed receiver did not contain a non-volatile memory card, but the handheld unit did. Track and ground-speed data for the occurrence flight was retrieved from the non-volatile memory card. Altitude information was not retained in the memory card.

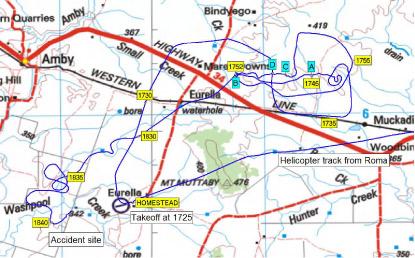

Figure 2 displays the GPS recorded track of the helicopter overlaid in blue on a 1 in 250,000 scale topographical map of the area. The local times that the helicopter was at various locations are depicted.

Figure 2: GPS track overlay, with the landing sites A, B, C and D

The GPS data showed that the helicopter landed five times during the flight. Those positions are depicted on the map and are described as follows:

| Position A | The helicopter landed at 1742 and departed at 1745. There was a water tank adjacent to that location. |

|---|---|

| Position B | The helicopter landed at 1749 and departed at 1752. |

| Position C | The helicopter landed at 1800 and departed at 1802. |

| Position D | The helicopter landed at 1805 and departed at 1807. |

| Position B | The helicopter returned to position B at 1823 and departed at 1827. |

The data indicated that, after the helicopter departed position B at 1827, it initially tracked almost directly toward the homestead, but that the track then veered south-west. That track was clear of the high ground indicated by the 400 m contour near Mt Muttaby, as depicted on the chart at Figure 2. There are distinct features in the helicopter's track after 1830, indicating that the pilot turned toward the homestead on four separate occasions between 1830 and 1840, only to turn away each time. The accident occurred on the fifth occasion that the helicopter's recorded track turned in the approximate direction of the homestead.

Subsequent to the occurrence, an employee from Eurella Station found that cattle had been moved from the paddock that included positions A, C, and D, to an adjoining paddock. Those paddocks were linked by a gate adjacent to position B. The employee recalled that the property owner had intended to move the cattle to the adjoining paddock and that the gate adjacent to position B was the gate through which he would have expected the cattle to be moved.

Pilot information

The pilot held an air transport (aeroplane) pilot licence and a command multi-engine instrument rating. He had extensive aeroplane flying experience, including regular public transport turbo-jet aircraft and corporate turbo-jet aircraft operations in Australia and overseas. His aeroplane flying experience exceeded 10,000 hours and included 1,418 hours of night flight and 711 hours of instrument flight.

The pilot obtained a private pilot (helicopter) licence on 23 September 1998 and had about 582 hours helicopter experience. He obtained a night VFR (helicopter) rating on 12 September 2000 and since that date had recorded about 11 hours helicopter night flight. Almost all of the logged flights were in the Sydney metropolitan area. Helicopter night flying recorded by the pilot in the two years prior to the occurrence was 0.4 hours on 23 August 2004 and 0.6 hours on 26 August 2004. That night flying most likely occurred during the latter stages of flights to the Sydney metropolitan area.

There was no record of the pilot having received any specific training in operating helicopters in remote areas or dark night conditions where there was little or no ambient lighting. No helicopter instrument flight time was logged.

The pilot held a valid medical certificate. Post-mortem and toxicology examinations did not reveal any pre-existing condition that might have affected the pilot's ability to safely conduct the flight.

Helicopter information

The pilot purchased the helicopter new in early August 2004. At the time of the occurrence the helicopter had operated for 34.1 hours. The maintenance release was valid and the documentation indicated that all applicable maintenance and regulatory requirements had been met.

The helicopter was equipped and certified for night VFR operations. Instrumentation included an airspeed indicator, artificial horizon, sensitive pressure altimeter, turn coordinator, horizontal situation indicator, global positioning system indicator, and vertical speed indicator.

The helicopter was equipped with twin landing lights in the lower nose section. The lights were fitted with 100 watt spot globes and, according to the Aircraft Flight Manual, were 'set at different angles to increase the pilot's field of vision'. Both lights were activated by the one switch which was mounted on the cyclic control centre post.

A row of eight amber warning lights located at the top of the flight instrument panel included a clutch warning light. A further six warning lights were positioned at the top of the centre pedestal.

The helicopter's engine was coupled to the rotor drive system via four double-stranded vee-belts. After engine start, an electric actuator would tension the belts when the pilot engaged the clutch switch. The actuator sensed belt tension and was automatically energised when the tension was less than required. The clutch warning light would illuminate whenever the clutch actuator circuit was activated. The Aircraft Flight Manual included a note regarding the clutch in Section 3, Emergency Procedures. The note stated that stretching of the belts often resulted in illumination of the clutch warning light for brief periods as the drive actuator readjusted belt tension. The note also included actions that the pilot should take after 7 or 8 seconds of illumination of the clutch light. One of those actions was to pull the clutch circuit breaker.

The helicopter was fitted with a Pointer (TSO-C91A) Model 3000-10 emergency locator transmitter (ELT). The unit was located on the left side of the rear fuselage.

The total flight time from Roma until the time of the occurrence was about 1 hour 35 minutes. Assuming a fuel usage rate of 60 L per hour, approximately 95 L would have been consumed during that time. On that basis, approximately 95 L should have remained at the time of the occurrence.

Wreckage information

opposite to the helicopter's direction of travel at impact. The impact severely crushed most of the cabin area and deformed the fuselage and tail boom structures.

Two distinct main rotor blade impact marks on the ground forward and to the right of the initial nose impact position, and the damage to the main rotor blades, indicated that the rotor blades were being driven by the engine at impact. The tail-rotor system was intact and there was no evidence that the fuselage was yawing at impact. There was no indication that the helicopter had struck any of the trees in the vicinity of the impact site.

The left fuel tank ruptured during the impact sequence and was empty. The right fuel tank was also empty. With the helicopter lying on its left side, the right fuel tank vent line was at the lowest part of the tank and would have allowed fuel to drain out. There was a strong smell of Avgas in the vicinity of the wreckage on the day after the accident.

The hydraulic system switch was found in the ON position.

Instrument panel light globe and instrument examination confirmed that electrical power was available to the instruments. There was no evidence of malfunction of any of the instruments.

The six warning lights at the top of the centre pedestal were destroyed by impact forces, preventing an assessment being made of their status at impact. The eight warning lights at the top of the flight instrument panel were intact. Examination of those light globes revealed stretching of the clutch warning light filament. Stretching indicates that the filament was hot and that electrical power was applied to the globe when it was subject to forces during the impact sequence. It was not possible to determine the length of time that the globe had been illuminated. Filament stretch was not evident in any of the other seven warning light globes from the top of the instrument panel.

Damage to the landing light globes prevented any assessment being made regarding their status at the time of the occurrence. The damage to the landing light switch indicated that it was in the ON position at impact.

The circuit breaker panel was destroyed by impact forces. The clutch actuator fuse was serviceable. The wreckage examination did not reveal any fault in the clutch system. Although the circuit breaker panel was destroyed, the evidence of electrical power to the clutch warning light indicates that the circuit breaker was engaged, and therefore the system was powered at the time.

The coaxial cable from the ELT unit to the external antenna had separated at the connector to the antenna base on the inside of the antenna mounting panel. The separation of the coaxial cable trapped the transmitted signal within the fuselage compartment. That rendered the ELT unit ineffective and prevented satellite detection of the signal. The separation of the cable appeared to have been as a result of impact forces. As a result, the search and rescue effort was significantly affected.

Specialist examination of the ELT revealed that it had activated upon impact and, when connected to a suitable antenna, was capable of transmitting a normal signal.

The engine was test run after removal from the wreckage and operated normally. The hydraulic pump and three hydraulic servos that formed part of the main rotor flight control system were removed from the wreckage for functional testing. The tests were conducted at the helicopter manufacturer's facility in the USA and supervised on behalf of the ATSB by a representative from the US National Transportation Safety Board. The tests confirmed that the hydraulic system components met the specifications for normal operation.

Meteorological information

Documents found in the helicopter included an Area 41 weather forecast valid from 0900 to 2100 on the day of the occurrence and the Roma terminal area forecast (TAF) valid from 1200 to 2400 on the day of the occurrence.

The area forecast indicated that the weather in the vicinity of Eurella Station would include areas of rain with locally moderate falls, scattered showers and isolated thunderstorms. The Roma TAF indicated that between 1500 and 2400 there would be 60 minute periods in which the visibility would be 2 km in heavy rain, with broken cloud2 at 700 ft.

An analysis by the Bureau of Meteorology indicated that during the late afternoon on the day of the occurrence, a surface trough was located from Camooweal to St George, with cold south-west winds to its west and northerlies to its east. The surface trough combined with an upper level trough over the southwest of the state to bring a large cloud band with widespread rain and isolated thunderstorms to the interior. The analysis of satellite imagery and synoptic reports, concluded that there was a high probability of rain in the Eurella Station area around the time of the occurrence, and most likely greater than 5 oktas of cloud cover. However, because the nearest weather radar station was about 200 km distant at Charleville, the amount of cloud cover in the area of the occurrence could not be confirmed.

Persons at and near Eurella Station variously reported that the weather conditions during the day of the accident were windy, with heavy cloud and showers.

Astronomical information

According to information published on the Geoscience Australia website, sunset and twilight times at Eurella Station on the day of the occurrence were:

Other information on the website indicated that the moon set at 1409 and was 79 degrees 31 seconds below the horizon at 1830 that evening.

Helicopter night VFR

The pilot's night VFR (helicopter) rating authorised him to act as pilot in command of private or aerial work flights at night under the VFR. Once issued, a night VFR rating remained permanently valid. To exercise the privileges of the rating, a pilot needed to complete a 1-hour night flight during the previous 12 months and one take-off and landing at night during the previous 6 months. There was no requirement for the holder of a night VFR rating to have any recent instrument flight time prior to conducting a flight at night.

A pilot operating under the VFR at night was required to operate in visual meteorological conditions that included a minimum of 5 km visibility. The Aircraft Flight Manual, Section 2, Limitations, included the following statements:

VFR operation at night is permitted when landing, instrument, and anti-collision lights are operational. Orientation during night flight must be maintained by visual reference to ground objects illuminated solely by lights on the ground or adequate celestial illumination.

At the time of the occurrence there was a 1,000 watt flood light on each of the northern and western walls of Eurella homestead, as well as lights in other buildings. However, there were many trees in the vicinity of the homestead, some of which were higher than the homestead roof. Depending on the altitude and position of the helicopter, the trees could have prevented those lights being seen from the helicopter (Figure 1). There was no other lighting in the general area, including at the airstrip adjacent to the homestead. The homestead lights, in effect, formed a 'point' source of light.

Spatial Disorientation

Spatial disorientation refers to a situation in flight in which the pilot fails to sense correctly the position, motion or attitude of the aircraft. When the condition is fully developed, the pilot is unable to tell which way is 'up'.

The risks of non-instrument rated pilots flying in conditions in which they are not able to orientate the aircraft by visual reference have been well known for over 50 years. During testing conducted on a group of non-instrument rated pilots, the average time before loss of control of the aeroplane, after visual reference was lost, was 178 seconds.5

US FAA Advisory Circular 60-4A, Pilot's Spatial Disorientation, was published in 1983 and was intended to inform pilots of the hazards associated with disorientation caused by loss of visual reference with the external environment. It included the following information:

Tests conducted with qualified instrument pilots indicate that it can take as much as 35 seconds to establish full control by instruments after the loss of visual reference with the surface.

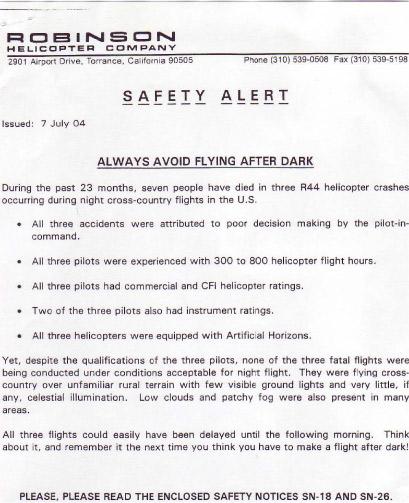

The helicopter manufacturer issued a safety alert and safety notices (SN) as a result of various occurrences and incidents, and included those notices in the Aircraft Flight Manual Section 10, Safety Tips. Two of the notices related to night flight - SN-18 Loss of Visibility Can Be Fatal, and SN-26 Night Flight Plus Bad Weather Can Be Deadly (see Appendix A). Safety notice SN-18 stated in part:

Helicopters have less inherent stability and much faster roll and pitch rates than airplanes. Loss of the pilot's outside visual references, even for a moment, can result in disorientation, wrong control inputs, and an uncontrolled crash.

Appendix A

1.On the day of the occurrence, other aircraft were refuelled from the Roma bulk fuel storage. The ATSB received no reports of fuel quality related problems involving those aircraft.

2. Forecast cloud was explained as 'few'-1 to 2 oktas (okta - a unit of visible sky area representing one-eighth of the total area visible to the celestial horizon), 'scattered'- 3 to 4 oktas, 'broken'- 5 to 7 oktas and 'overcast'- 8 oktas.

3. Sunset is defined as the instant in the evening under ideal meteorological conditions, with standard refraction of the sun's rays, when the upper edge of the sun's disk is coincident with an ideal horizon.

4. Ending of evening civil twilight is defined as the instant in the evening when the centre of the sun is at a depression angle of six degrees below an ideal horizon. In the absence of moonlight, artificial lighting or adverse atmospheric conditions, the illumination is such that large objects may be seen, but no detail is discernible.

5. Bryan, L.A., Stonecipher, J.W. & Aron, K. 1954. 180-degree turn experiment. University of Illinois Bulletin. 54(11), 1-52.

ANALYSIS

The investigation found that there was no evidence of a pre-existing defect in the helicopter that may have contributed to the occurrence, nor was there any evidence of a medical condition that could have affected the pilot's ability to control the helicopter. Consequently, the investigation concluded that in the prevailing environmental conditions, the accident was consistent with pilot spatial disorientation. This analysis examines the development of the occurrence and highlights a significant risk associated with night VFR operations.

The pilot departed for Eurella homestead 6 minutes after civil twilight in moonless, overcast, and probably showery conditions that were likely to restrict visibility to less than the required 5 km. Except for the homestead lights, the ground lighting or celestial illumination required by the Aircraft Flight Manual was not available. Although the pilot had flown at night on two recent occasions (23 and 26 August 2004), those flights did not fully satisfy the night VFR recency requirements and were probably over a well lit area. Given the pilot's limited recent and overall helicopter night flying experience, and the forecast weather conditions, it is unlikely that the pilot planned to conduct the return flight at night. The pilot had probably used the helicopter to move cattle and that task may have taken longer than expected. The proximity of the homestead, the local knowledge of his passenger, the night VFR capability of the aircraft and access to GPS information may have influenced the pilot to attempt the return flight.

The track information recovered from the hand-held GPS showed manoeuvring after 1830 that suggests that the pilot, probably using GPS information, made several attempts to track to the homestead, but was unable to do so. It is likely that during the manoeuvring the pilot was at a low altitude, attempting to maintain visual contact with surface features, possibly with the assistance of the landing lights. Such visual contact would have enabled control of the helicopter and clearance from terrain. In the absence of a consistently discernable horizon, any visual contact with the homestead lights would not have enabled the pilot to determine the helicopter's attitude. Prior to the impact, the pilot may have lost visual contact with the surface due to cloud and/or rain and become spatially disorientated.

The pilot may have attempted to control the helicopter by reference to the flight instruments. However, he had not logged any instrument flight time in a helicopter and had not been exposed to significant night-flight away from metropolitan areas. The relative instability of the helicopter and the different operating environment meant that the pilot's considerable aeroplane night and instrument flight experience was not directly transferable to night VFR helicopter operations. Consequently, spatial disorientation could have developed rapidly.

Flying the helicopter at a low altitude at night with cloud and/or showers in an area with little lighting was a very demanding task with little margin for error. However, once the helicopter became airborne after civil twilight, there were few options available to the pilot. The pilot's lack of helicopter instrument flight experience would probably have precluded consideration of climbing to the lowest safe altitude and tracking to an aerodrome with an instrument approach. Given that the adverse weather was widespread, diversion to another location while maintaining external visual reference was also an unlikely option.

A landing at a location other than the homestead was an option. It is possible that the accident occurred when the pilot became spatially disorientated in the adverse conditions while attempting to land the helicopter. However, it is also possible that, unable to communicate with the homestead, the pilot avoided an out-landing due to the consequent difficulty in reaching the homestead without transport.

Illumination of the clutch light as indicated by the stretched filament may have resulted from clutch operation during flight or from disruption during the impact. If the clutch light had illuminated during flight it may have distracted the pilot and contributed to spatial disorientation.

As a result of the separated ELT antenna cable, the search and rescue effort was significantly affected. However, in this case, the nature of the impact and the extent of injury to the occupants indicated that the search and rescue effort would not have influenced their survivability.

The circumstances of this occurrence highlight the risk of spatial disorientation during night VFR operations and reinforce the significance of the cautions included in the helicopter manufacturer's safety notices SN-18 and SN-26.

SIGNIFICANT FACTOR

The pilot departed after civil twilight in conditions where a natural horizon was probably not discernible and consistent visual reference to surface features was not likely.

SAFETY ACTION

Manufacturer

On 17 November 2004, the helicopter manufacturer advised that it had contacted the emergency locator transmitter (ELT) manufacturer concerning the ELT antenna coaxial cable connectors. The ELT manufacturer had undertaken to test coaxial cable connectors with a 30 lb. tension load. Connectors held in stock by the helicopter manufacturer would also be tested. The helicopter manufacturer advised that it was converting to the new 406 MHz capable ELTs. The antenna connector for the new installation would be crimped by the helicopter manufacturer. The style of crimping used by the helicopter manufacturer has been tested and could typically withstand in excess of 100 lb tension. The helicopter manufacturer believed that those actions would prevent failures of the type that occurred to the ELT installation in the occurrence helicopter.

ATSB

A summary of this accident report will be included in a future edition of CASA's Flight Safety Australia magazine.