Sequence of events1

On 30 August 2004, shortly before 1200 Western Standard Time, the owner-pilot of a twin-engine Cessna Aircraft Company 421C Golden Eagle (C421) aircraft, registered HB-LRW, commenced his take-off from runway 32 at El Questro Aircraft Landing Area (ALA). The private flight was to Broome, where the pilot intended resuming the aircraft delivery flight from Switzerland to Perth. The available documentation indicated that the flight segments en route to Australia had all been to international or major aerodromes.

The pilot of a Cessna Aircraft Company 210 (C210) and his two passengers in the runway 32 parking area witnessed the take-off. Those witnesses reported that the C421 pilot carried out a pre-flight inspection of the aircraft prior to boarding for the take-off. During that inspection, he was observed preparing for and conducting a fuel drain check under the left wing, and to have removed some weed-like material from the right main wheel. He then loaded a small amount of personal luggage into the aircraft cabin, before he and the sole passenger boarded.

The C210 pilot witness, who reported having observed a number of twin-engine aircraft operations at another aerodrome, did not comment on the nature of the pilot's start and engines run-up checks. The passenger witnesses reported that the pilot of the C421 made a number of unsuccessful attempts to start the left engine, before reverting to starting the right engine. He then started the left engine and moved the aircraft clear of the C210 in order to conduct his engine run-up checks. The passenger witnesses reported that during those checks they heard a 'frequency vibration' as the C421 pilot manipulated the engines' controls.

The witnesses at the parking area reported that the C421 pilot taxied the aircraft onto the runway and applied power to commence a rolling take-off.2 They, together with a hearing witness3 located to the north of the ALA indicated that the engines sounded 'normal' throughout the take-off. Witnesses who observed the take-off reported that the aircraft accelerated away 'briskly'. The pilot witness stated that the take-off roll and lift-off from the runway appeared similar to other twin-engine aircraft take-offs that he had observed.

The witnesses at the parking area also stated that, shortly after lift-off from the runway, the aircraft banked slightly to the left at an estimated 10 to 15 degrees angle of bank and drifted left before striking the trees along the side of the runway and impacting the ground. There was no report of any objects falling from the aircraft, or of any smoke or vapour emanating from the aircraft during the take-off. The aircraft was destroyed by the impact forces and post-impact fire. The pilot and passenger were fatally injured.

Personnel information

The 60-year-old pilot was appropriately licensed and held the relevant aircraft and other endorsements to conduct the flight. It was reported that the pilot had accumulated more than 975 hours experience flying the Cessna 421 B and C model aircraft over the preceding 10 year period and had at least 2,100 total flying hours. The pilot had flown about 50 to 60 hours in the aircraft since March 2004 and held a valid Class 2 medical certificate. He last underwent an electro cardiogram examination (ECG) in support of the revalidation of his medical certificate, on 22 September 1999. That included an annotation by the consulting doctor that the ECG was 'normal'. The pilot's family indicated that the pilot's personal logbook would have been in the aircraft at the time of the accident.

The passenger had accompanied the pilot for the majority of the flight from Switzerland to Australia, but was reported to have been a little nervous about take-offs and landings.

The pilot and passenger arrived at the El Questro ALA at about 1330 on 28 August 2004 and landed on runway 14. They were reported to have spent the next two days relaxing in the tourist resort and homestead. During that time, the pilot was observed by staff to have retired for bed by about 2200 and appeared from his room by about 0930 each day. During his stay the pilot ate regularly, drank alcohol only socially, and recounted many of his experiences during the delivery flight to staff and other guests. That did not include the discussion of any difficulty starting the aircraft engines, of any anomalies during the after-start checks and procedures, or during the flight to El Questro. The pilot was reported to be fit and well and in good spirits on the morning of the accident.

Aircraft information

General information

All of the aircraft's original maintenance documentation was reported to be on board the aircraft for the flight to Australia and was subsequently destroyed in the post-impact fire. The loss of the aircraft's maintenance documentation and historical records precluded a thorough review of the aircraft's documentation concerning compliance with applicable airworthiness directives and service bulletins. Aircraft and engine maintenance and airworthiness-related issues were reconstructed from available secondary documentation, including: pilot and other relevant party e-mails and facsimile messages, and data from international regulatory and other agencies.

| Forward limit: 152.59 ins at 7,450 lbs or less and 147.14 ins at 6,100 lbs or less with a straight line variation between those points | |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Cessna Aircraft Company |

| Model | 421C Golden Eagle |

| Serial number | 421C-0633 |

| Registration | LB-LRW |

| Year of manufacture | 1979 |

| Export Certificate of Airworthiness | Certificate number 3588/04 i ssued in Switzerland on 27 February 2004 |

| Certificate of Registration | Swiss certificated4 |

| Total time airframe | Between 3,244.6 and 3,254.6 hours (estimated)5 |

| Maximum allowable take-off weight | 7,450 pounds (lbs) |

| Actual take-off weight | 6,600 lbs (estimated) |

| Allowable centre of gravity limits (measured aft of the reference datum) | Aft limit: 157.95 inches (ins) at 7,450 lbs or less |

| Centre of gravity at occurrence | 157.5 ins (estimated) |

E-mail correspondence from the pilot dated 16 September 2003 indicated that the aircraft was equipped with the Robertson Short Take-off and Landing (R-STOL) Kit. That kit included the following changes to the configuration of the aircraft:

- Replacement of the existing trailing-edge split flaps with R-STOL slotted flaps for use with the flaps extended 10°. The effect was to reduce the aircraft stall speed and the best single-engine climb speed.

- Introduction of a scissors-type aileron bell crank that allows symmetrical aileron droop with extension of the flaps. This had the effect of further reducing the aircraft stall speed.

- Introduction of a spring/cable flap/elevator interconnect to minimise pitch trim changes with flap extension or retraction.

In this instance, and as discussed in the wreckage examination discussion at page 13, and the asymmetric or 'split' flap discussion at page 19, the aircraft flaps were retracted. In that case, the R-STOL kit would have had no effect on the aircraft take-off performance, and the aircraft's performance would have been in accordance with a standard C421C in a flaps retracted configuration.

The aircraft's take-off weight and centre of gravity were estimated by the investigation to be within the limits published in the C421C's Pilot's Operating Handbook (POH). The POH also included a Normal Take-off Distance prediction chart. Application of the estimated aircraft take-off weight and reported ambient conditions for a normally configured C421C to that chart resulted in a predicted take-off roll that approximated the estimated take-off distance reported by the witnesses located at the runway 32 parking area.

Aircraft history

The aircraft was manufactured in the United States (US) and was US-registered until 1992, when it was exported to Switzerland. It was operated in Switzerland in the private category until purchased by the pilot in December 2003. E-mail correspondence from the pilot and dated 4 December 2003 indicated that a Swiss maintenance organisation would commence a 'new annual/200-hours check' on 10 December 2003. The available aircraft maintenance records indicated that the total aircraft flight hours were 3,192 hours 40 minutes as at 10 December 2003. That corresponded with the initial entry made by the pilot in the aircraft maintenance record after a flight in the aircraft on 2 March 2004. The last entry in the aircraft's maintenance record, that was available to the investigation, was a total of 3,233.6 aircraft flight hours at Ahmedabad, India on 9 August 2004.

A number of aircraft anomalies or maintenance requirements needed resolution while the aircraft was en-route from Switzerland to Australia. They included:

- In Malta, where an approved maintenance facility:

- replaced leaking right engine push rod tube seals

- replaced a faulty left engine vacuum pump

- identified a leaking right main landing gear oleo and disassembled the landing gear oleo and installed new packings and 'o' ring seals before reinstalling the oleo on the aircraft.

- In Cyprus, where a crack was discovered in the right engine crankcase that necessitated the replacement of that engine.

- In the United Arab Emirates and Oman, where a number of attempts were made by local engineering companies to resolve a problem with the operation of the aircraft's landing gear. That ultimately required the replacement of a selector valve and hydraulic line.

In addition, the pilot established communications with a twin-engine Cessna owners group in an effort to fault analyse ongoing problems with:

- the left and right hydraulic pumps that supplied the necessary hydraulic pressure to extend and retract the landing gear, and

- the right alternator warning light, which was reported to commence flickering after about 30 minutes flight time. That anomaly was reported to have commenced in July 2004.

The resolution or otherwise of those two anomalies was not documented by the pilot.

On arrival in Australia, a 50-hourly inspection of the aircraft was carried out by a Broome aircraft maintenance company on 26 August 2004. The total airframe hours at the time of that inspection were not noted on the inspection work sheet. At the conclusion of the inspection, a company engineer carried out a ground run of the engines with the pilot accompanying him in the right front seat. The engineer reported that during that ground run, both engines started on the first attempt and ran normally without any anomalies being noted.

Engines and propellers

The aircraft engine details were as follows:

| Left engine | Right Engine | |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Teledyne Continental Motors | Teledyne Continental Motors |

| Model | Model TSIO-520-L | Model TSIO-520-L |

| Serial number | 245846-H | 277006R |

| Date of last overhaul | Unable to be determined | 19 May 2004 |

| Date of last maintenance | 26 August 2004 | 26 August 2004 |

| Type of last maintenance | 50-hourly inspection | 50-hourly inspection |

| Hours since last overhaul | 767 hours (estimated6) | 39.3 hours (estimated7) |

The available right engine documentation indicated that it had been certified by a US Federal Aviation Administration-approved maintenance organisation. In addition, the documentation confirmed that the engine complied with all of the engine manufacturer's service bulletins and service letters that affected the engine up to and including 17 May 2004.

The details of the propellers, including their relationship to their respective engines, were determined from examination of the pilot's e-mail correspondence and the aircraft sales brochures, and included:

| Left propeller | Right propeller | |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | McCauley | McCauley |

| Model | 3FF32C501A 90UMB-0 | 3FF32C501A 90UMB-0 |

| Serial number | 787999 | 779463 |

| Date of last overhaul8 | Year 2001 | Year 2001 |

| Date of last maintenance | 26 August 2004 | 26 August 2004 |

| Type of last maintenance | 50-hourly inspection | 50-hourly inspection |

| Hours since last overhaul | 330 (estimated) | 330 (estimated) |

Meteorological information

A Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) post-accident assessment of the wind at the ALA at the time of the accident was that it would have been a light southerly at around 5 kts. An estimation of the ambient temperature and humidity at the ALA was not included in the BoM assessment. The BoM indicated that any difference between the BoM estimation of the prevailing wind and that reported by any witnesses could have been due to local topographical effects at the site. The BoM advised that a possible influencing factor on the aircraft's take-off could have been the presence of a dust devil9, but that the presence of that phenomenon would also require confirmation by any witnesses at the scene of the accident.

The witnesses at the landing area estimated that the wind affecting the runway was south-easterly at 5 to 10 kts at the time of the take-off. There were no dust devils reported in the vicinity of the runway at that time, and another pilot who was conducting charter work in the vicinity of the landing area indicated that there was minimal thermal activity.

Aerodrome and communications information

Aerodrome

The El Questro ALA, designation YEQO, is located at 16°00.5'S, 127°58.5'E and is at an elevation of 300 ft above mean sea level. The dirt runway is aligned south-east (runway 14) to north-west (runway 32) and is 1,400 m long and about 15 m wide. Windsocks are located at the northern side of the threshold to runway 14 and at the tourist resort homestead, which is located about 1 km south-east of the landing area.

The manager of the tourist resort indicated that when making bookings with the resort, visiting pilots generally included that they were 'self-fliers'. That was the case with the occurrence pilot. In addition, it was reported that the pilot telephoned the resort manager on the morning of 28 August 2004 and nominated a SARTIME10 for his arrival at El Questro. During that call, the pilot confirmed that he was comfortable with the location and details of the ALA. Other twin-engine aircraft of similar size to the C421 Golden Eagle were reported by the resort manager to have operated to, and continue to operate to, the El Questro ALA.

It was reported that in mid-March each year, just prior to the commencement of each tourist season, resort staff conducted a routine inspection of the runway and environs. As a result of those inspections, any newly growing vegetation was cleared from the runway and its surrounds, runway markers were repainted as required and other actions were undertaken by resort staff as and when required. In addition, the resort manager stated that he routinely consulted with aircraft operators who regularly fly to the resort, in order to confirm the ongoing suitability of the ALA for aircraft operations.

Communications

The charter pilot indicated that just prior to 1200, he exchanged a number of radio transmissions with the pilot of an unknown aircraft on frequency 126.7 Mhz in order to coordinate that pilot's take-off from the ALA. The charter pilot reported observing a plume of smoke from the vicinity of the ALA shortly thereafter, and that he did not hear a distress radio transmission. There was no facility at the ALA to record pilots' radio transmissions.

Wreckage information

The impact forces and post-impact fire sustained by aircraft structures in occurrences of this type can result in erroneous control position indications. In general, the position of the flight controls after impact cannot be relied upon as evidence of the aircraft's pre-impact configuration.

Overview of accident site and aircraft wreckage

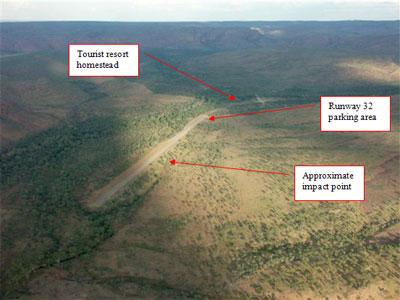

The accident site was located on level ground, alongside a dry creek bed about 106 m to the left of the runway centreline and abeam a point on the runway about 888 m from the runway 32 threshold. A photograph of the general location of the accident site is at Figure 1. Groupings of rocks were located about the site and the surrounding light scrub was interspersed with isolated larger Boab and other trees.

Figure 1: General location of the accident site

A number of trees to the left of the runway were struck by the aircraft before it impacted the ground. Those trees were oriented along a line at about 15° to the left of the runway heading. Laser range equipment was used to measure the distances of those tree strikes from the aircraft wreckage. Trigonometry was then applied to the laser ranges in order to estimate the height of the strikes above ground level as follows:

- The initial tree strike was to a tree located about 66 m to the left of the runway centreline and at an estimated height of about 8.2 m (27 feet (ft)).

- The final tree that was struck prior to ground impact was located about 97 m from the runway centreline. That tree was struck at an estimated height of about 10.7 m (36 ft). The location of the left-wing tip and remnants of the left navigation light in the immediate vicinity of that tree indicated that tree strike had been by the left wing.

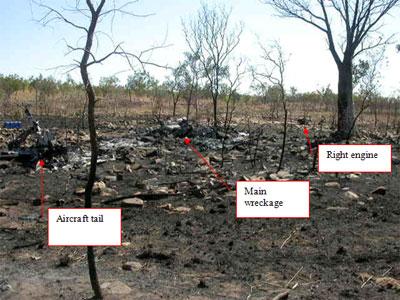

The aircraft impacted the ground about 33 m beyond the last tree, in a left-wing low attitude and cartwheeled counter-clockwise. The right wing and tail then struck the ground. During the impact sequence, the right engine separated from the airframe mounts and was thrown about 26 m from the main wreckage and the tail section separated from the aircraft. The main wreckage came to rest upright, with the nose of the aircraft facing south-east. All structural components and flight control surfaces were accounted for in the vicinity of the impact point. A severe post-impact fire destroyed the majority of the aircraft's fuselage, wings, tail section, cockpit and cabin, and damaged the left engine. The right engine sustained minor fire damage from a scrub fire that was started by the aircraft fire. A photograph of the aircraft wreckage is shown at Figure 2.

Figure 2: Aircraft wreckage

Wreckage examination

The investigation conducted a post-accident inspection of runway 32 from the threshold of the runway to a point on the runway abeam the ground impact point. That inspection found no evidence of any: bird or other animal remains; gouges, scrapes or other abnormal ground marks; or the presence of any detached aircraft items or components.

Very few ground impact scars or marks were able to be examined at the accident site due to them having been partially obliterated by the vehicles and personnel involved in the initial firefighting and rescue response. However, a number of rocks located in the dry creek bed had evidence of propeller impacts at substantial propeller revolutions per minute (RPM).

Both wing structures were destroyed by the fire. The right-wing forward attachment point was intact, and the aft spar was fractured in overload consistent with upward loads in excess of design limits. The left-wing structure had separated at the wing spar outboard of the engine nacelle, having also failed in overload due to the ground impact.

The fire severely damaged the aircraft fuel system. Both wing tanks were destroyed, and their associated auxiliary pumps were severely damaged. The left- and right-over-wing filler caps were secure. Damage during the impact, and the post-impact fire precluded the recovery of a fuel sample from the wreckage.

Both of the engines' air boxes and both turbocharger compressor turbines, together with their associated valves were fire damaged. On-site examination of the turbochargers did not reveal any anomalies, or foreign object, or other damage that might have adversely affected their operation. Deformation damage to the right engine's exhaust system was consistent with engine operation at ground impact. The left and right engines were recovered from the accident site and transported to an authorised overhaul facility for subsequent inspection under the supervision of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB).

All six propeller blades separated from their respective hubs during the ground impact. Four intact propeller blades and segments from the remaining two blades were recovered from the accident site for subsequent technical examination.

Both engine propeller hubs flanges displayed indications of rotation at high RPM at the time of ground impact and were recovered from the accident site for subsequent technical examination. Severe impact damage to the propeller static stops prevented any determination of the propeller pitch settings at the time of ground impact. All of the propeller counterweights were recovered and examined on site. That examination identified overload of the threaded inserts, to the extent that a number of the counterweights had separated from their housing. That corroborated the earlier evidence of high engine RPM at the time of ground impact.

All of the cockpit and cabin seats and structures, along with the seat belts and their attachments, were destroyed by the fire. Most of the cabin fittings and cockpit, including instrumentation and switches were also destroyed. The nature of the damage to the switches was such that their position prior to the ground impact could not be ascertained. The control columns and flap actuator were destroyed in the fire and the engine controls, and the cockpit instruments and radios were severely damaged. While that prevented the examination of most of the instruments, the attitude indicators and annunciator panel were recovered for subsequent technical examination.

Pre-impact flight control continuity was confirmed for the elevator and rudder control surfaces. Flight control continuity was evident for the ailerons, from the cockpit controls aft to the point where the wing impact damage occurred. A continuity check of the engine controls was not possible as a result of the fire damage. The nature of the damage to the right flap indicated that it was retracted at the time of ground impact. The more extensive damage to the left flap precluded a definitive assessment of its position at ground impact. The landing gear was fully extended. The tyres were destroyed by the fire. The severe disruption of the tail structure rendered the determination of the aircraft trim measurements inconclusive.

Examination of components recovered from the wreckage

The left and right engines were disassembled and inspected at an authorised overhaul facility under the supervision of the ATSB and with the engine manufacturer's representative in attendance. That inspection found no evidence of internal mechanical failure within either engine, or of their associated accessories or components that would have prevented the normal operation of either engine prior to the accident.

Technical examination of the propellers and propeller segments indicated multiple high-energy hard object impact signatures on all blade surfaces. Several of those impacts were of sufficient force to have caused ductile shear of the outer airfoil sections. In addition, there was backward curling or loss of material from the blades' leading edges, with associated chordwise scoring and gouging across the airfoil sections. That was consistent with each propeller being actively driven by a comparable amount of power from within the respective engine's upper operating range at the time of ground impact.

Both engine propeller hubs sustained similar multiple fractures to their aluminium alloy housings that was consistent with ductile overload during the accident sequence. There was no indication of any pre-impact cracking or manufacturing defects. The propeller hubs were exposed to gross bending loads through the blade sockets, which was assessed as being consistent with the magnitude of the impact forces that damaged the propellers.

The technical examination of the primary attitude indicator proved inconclusive due to the extensive heat damage to the instrument. There was evidence of rotational scoring to the inside of the secondary attitude indicator's instrument case and to the gyro armature, which indicated that pneumatic drive was available to the aircraft's vacuum instruments at the time of ground impact.

The filaments from the annunciator panel globes were distorted and encased in molten glass as a result of the fire. That prevented the analysis of whether any of those lights had been illuminated at the time of ground impact.

Medical and pathological information

A review of the pilot's aviation-related medical records and the results of the pilot's postmortem examination found no evidence of any pre-existing medical disease, sudden illness or incapacitation that may have affected his ability to control the aircraft.

Fire

There was no report by the witnesses to the take-off, or evidence, of an in-flight fire. The tourist resort volunteer fire-fighting crew responded to the accident site and scrub fires.

The source of the intense post-impact fire was fuel that had spilled from the ruptured wing fuel tanks. The ignition source of the fire could not be confirmed but was likely the hot engine exhausts.

Survival aspects

The emergency locator transmitter (ELT) was destroyed in the post-impact fire. There was no report from the charter pilot, or from the search and rescue authorities to indicate that the ELT had activated on ground impact.

The destruction of the cockpit and cabin from the combined effects of the impact forces and fire rendered the accident non-survivable.

Tests and research - aircraft fuel

The last recorded refuel of the aircraft was the addition of 594 litres of aviation gasoline 100 at Broome on 27 August 2004. It was reported that the pilot refuelled the aircraft's tanks to capacity. The investigation team quarantined a sample of that fuel for subsequent analysis by an approved National Association of Testing Authorities facility. That analysis indicated that the fuel:

- was clear and bright

- was free from water and sediment

- conformed to specification for aviation gasoline 100.

Examination of the Broome fuel supplier's records confirmed that 18 other aircraft were refuelled from that source after the occurrence aircraft on that day. There were no reports from the pilots of those aircraft of any fuel-related problems.

There were no aircraft refuelling facilities at El Questro.

Additional information

Use of aerodromes

Civil Aviation Regulation 92 places responsibility for ensuring that an aircraft landing area is suitable for landing or take-off with the pilot in command. In addition, the regulation requires the pilot to have regard to the prevailing weather conditions and other circumstances affecting the proposed landing or take-off. The determination by a pilot of which other circumstances should be considered is not stated in that regulation.

Civil Aviation Advisory Publication (CAAP) 92-1(1): Guidelines for Aeroplane Landing Areas includes guidance on the factors that may be considered by a pilot when determining the suitability of a potential landing area. While there was no evidence that the pilot had considered the requirements of the CAAP prior to planning his arrival at the El Questro ALA, the investigation applied the minimum landing area physical characteristics recommended by the CAAP to the pilot's take-off from runway 32 until the point at which the aircraft first struck a tree to the left of the runway. That examination determined the following relevant recommended parameters for the take-off:

- minimum runway width - 15 m

- required runway length - about 624 m

- suitable lateral transitional slope, which the CAAP notes could allow for a desirable area of increased lateral clearance during the take-off and may reduce wind shear if near tall trees - maximum obstacle height of about 7.2 m at 66 m from the runway centreline.

The pilot's family indicated that the pilot had operated at a gravel airstrip in the south-west of Western Australia on a number of occasions over the previous 3 years. In addition, the family reported that the pilot drove to El Questro in June 2003 and, during that visit, most likely observed the ALA.

Preparation for flight

The pilot submitted a flight notification to Airservices Australia on the morning of the accident, for a 2 hours 15 minutes flight under the Visual Flight Rules from El Questro to Broome. The investigation estimated that 740 lbs of fuel remained after the reported 2-hour flight from Broome to El Questro, and the POH stated that 50 lbs of fuel was required for 'taxiing for take-off'. That, and the endurance nominated by the pilot in the flight notification, indicated that sufficient fuel was carried for the planned flight to Broome.

The POH stated that the aircraft equipment included a control column lock that restricted control column movement and held the ailerons in a neutral position and the elevators at about 10° trailing edge down. The aircraft manufacturer indicated that the design of the control column lock was such that, if inadvertently left engaged by a pilot, the aircraft would be unable to take-off. The available documentation indicated that an optional rudder gust lock was also included in the aircraft equipment. The POH stated that engagement of that lock required the rudder to be centralised and the elevators to be moved to the fully 'down' position. Disengagement of the rudder lock was possible either manually during the aircraft pre-flight, or automatically as the elevator was moved up through the 6° 'down' position. Due to the damage to the aircraft, the investigation was unable to confirm the position of these locks.

Manufacturer data

The POH promulgated the necessary checks to be carried out by the pilot when operating the aircraft. That included confirmation of the selection of the left and right engines to the left and right main fuel tanks respectively as part of the following checks: before start, before take-off and during the descent. In addition, the POH stated that:

A take-off with one main tank full and the opposite tank low on fuel creates a lateral unbalance. This is not recommended since gusty air or premature lift-off could create a serious control problem.

The published take-off technique included the requirement for the pilot to raise the nose wheel at 95 kts indicated air speed (KIAS) and lift the aircraft from the runway at 100 KIAS. In addition, the POH included a description of the aircraft stall including that:

- the stall characteristics are conventional

- there is an aural stall warning device that operates at 5 to 10 KIAS above the stall in all configurations

- the stall is preceded by a mild, aerodynamic buffet, which increases in intensity as the stall is approached

- the power-on stall occurs at a very steep pitch angle, either with or without flaps extended

- it is difficult to inadvertently stall the aircraft during normal manoeuvring.

Stall speeds were published in the POH for a number of aircraft configurations. None of those configurations reflected the aircraft's take-off configuration. At the estimated aircraft weight and with wings level, the maximum stall speed for the published configurations was calculated as 83 KIAS. The increase in stall speed at 15° angle of bank for all published configurations was about 2 KIAS.

The manufacturer's Pilot Safety and Warning Supplements identified a rare, but potentially serious problem known as 'split wing flaps'. Split or asymmetric wing flaps may result from a mechanical failure in the flap system and cause the flap position on one wing to differ from that of the opposite wing flap. The result is a tendency for the aircraft to roll in the direction of the retracted flap. Depending on the experience and proficiency of a pilot, the manufacturer indicated that any rolling tendency caused by a split flap situation may be controlled with opposite aileron. In addition, there was the potential for a pilot to apply differential power in a multi-engine aircraft to assist in managing the condition. This is discussed further in the Analysis under 'Take-off'.

- Only those investigation areas identified by the headings and subheadings were considered to be relevant to the circumstances of the occurrence.

- A take-off commenced by a pilot without pausing an aircraft in a stationary position on a runway, or decreasing the speed of an aircraft on arriving at a runway intended for use for a take-off.

- A witness that heard, but did not observe the take-off.

- On 14 November 2003, the pilot submitted an application to the Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) to reserve an Australian aircraft registration in anticipation of registering the aircraft in Australia. That reservation was granted by CASA.

- Based on the 50-hourly inspection that was carried out in Broome on 26 August 2004 being conducted within the potential 10-hour extension period that had been authorised by the Swiss regulatory authorities. That was between 50 and 60 hours after an annual/200 hours check that was reported as being commenced in Switzerland on 10 December 2003, and included the 2.0 hour flight to El Questro ALA.

- Derived from e-mail correspondence from the pilot dated over the period 16 September 2003 to 24 August 2004 and the available aircraft and engine documentation.

- Derived from the right engine Export Certificate of Airworthiness of 19 May 2004 and e-mail correspondence from the pilot dated 29 July to 19 August 2004.

- Precise date not available.

- A miniature whirlwind with the potential to be of considerable intensity, and to pick up dust and perhaps other items and carry them some distance into the air.

- The time nominated by a pilot for the initiation of Search and Rescue action if a report has not been received by the nominated unit.