At about 2017 Eastern Standard Time on 15 August 2004, a Mooney Aircraft Corporation M20K aircraft, registered VH-DXZ, descended into the ocean off Bokarina, Queensland. The pilot, who owned the aircraft and was the sole occupant, did not survive the impact.

The pilot held a private pilot (aeroplane) licence and a night visual flight rules (VFR) rating. His logbook recorded his total flying experience at the time of the accident as about 1800 hours, 142 of which were at night. The pilot last flew at night on 19 June 2004, and in actual or simulated instrument meteorological conditions, during 1998. His three most recent flight reviews were logged as day flights, with no instrument or night flight recorded.

The weather conditions in the area at the time of the occurrence were benign. Astronomical twilight occurred at 1846 and the moon set at 1637.

The wreckage was recovered 13 days after the accident. An examination revealed that at the time of impact; the engine was delivering high power, the instrument lights were receiving electrical power, and the gyroscopic instruments were receiving pneumatic power.

The circumstances of the accident are consistent with a loss of control due to the pilot becoming spatially disoriented after flying into an area of minimal surface and celestial illumination. Physiological and cognitive factors may have contributed to the development of the accident. However, the factors that contributed to the aircraft descending into the water could not be conclusively established.

This accident highlights the need for night VFR pilots to manage the risk of spatial disorientation in dark night conditions by maintaining proficiency in instrument flight.

FACTUAL INFORMATION

History of the flight

At about 1730 Eastern Standard Time on 15 August 2004, the pilot of a Mooney Aircraft Corporation M20K aircraft, registered VH-DXZ, departed Cobar, NSW, on a private flight to Caloundra, Qld. The flight was conducted under the visual flight rules (VFR), with the latter part at night.

At about 2015, several people saw and heard the aircraft, with its wing tip strobe lights flashing, flying low in a northerly direction over Bokarina, 8 km north-north-east of Caloundra aerodrome. One witness said that the engine sounded as though it was 'struggling and cutting out'. Two other witnesses described the engine sound as a 'steady drone', while another said it sounded like it was 'turning at low [revolutions], as if it was powered down for a landing'.

The aircraft was then observed to turn east and cross the coast before descending steeply and impacting the water. The impact was accompanied by a bright flash. The aircraft wreckage was located 4 days later, approximately 1.5 km east of Bokarina beach, at a depth of about 16 m. The pilot, who owned the aircraft and was the sole occupant, did not survive the impact.

Earlier that afternoon, the pilot had flown from Caloundra to Cobar with one passenger. The passenger remained at Cobar and reported that the flight from Caloundra had been uneventful and that they arrived at Cobar at about 1700. The refueller advised that the pilot refuelled the aircraft with 156 L of avgas (apparently to full tanks) and checked the engine oil before departing on the return flight to Caloundra.

The pilot lived at Bokarina and family members reported that he did not normally fly over his home on returning from a flight. They indicated that the pilot's car was at the aerodrome, so he did not need to be met and driven home. They assumed that the purpose of flying over the house was to let them know that he would be home soon.

Recorded information

The pilot was not required to report to air traffic control during the flight and there was no record of him having done so. The Caloundra Common Traffic Advisory Frequency did not have a recording capability.

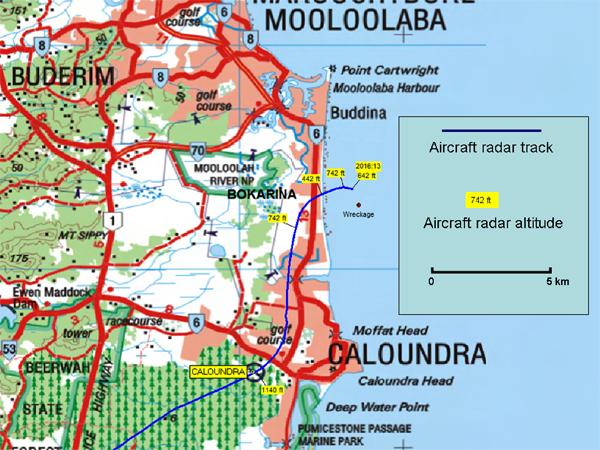

A pilot conducting a VFR flight was required to operate the aircraft's secondary surveillance radar (SSR) transponder on code 1200 in airspace not subject to air traffic control. The Mooney's SSR track for the flight was recorded by The

Australian Advanced Air Traffic System. That data showed that the aircraft first appeared on radar at 1903, north of Moree, NSW, on the direct track from Cobar to Caloundra at 11,300 ft. The aircraft maintained that altitude until 1937, when it commenced descent, passing through 10,000 ft at about 1940, and 5,000 ft at about 1958. It maintained a steady track and descent profile, and was overhead Caloundra at 2014, at 1,140 ft. The aircraft then maintained a relatively constant altitude and tracked north towards Bokarina (Figure 1).

At 2015, the aircraft commenced a further descent and when overhead Bokarina, turned right and headed east-north-east, towards the ocean. Radar data indicated that the aircraft descended to 442 ft about the time it flew over the beach. The aircraft's altitude then increased, reaching a maximum of 742 ft. The last valid radar information was recorded at 2016:13, and indicated that the aircraft had entered a descending right turn. The recorded radar data did not reveal any abrupt or abnormal changes in the aircraft's altitude, groundspeed, or track. The recorded speeds were consistent with normal cruise and descent speeds for the aircraft type (Appendix A).

Figure 1: The aircraft's radar-recorded track

Pilot information

The pilot purchased the aircraft in May 1994, and was issued with a private pilot (aeroplane) licence in July 1994. His logbook recorded his total flying experience at the time of the accident as about 1800 hours, 142 of which were at night. In April, May and June 2004, the pilot logged 5, 0.5 and 5.4 hours night flying respectively, all in DXZ. In those same months, he also logged 20.8, 12.3, and 25.4 hours day flying. The pilot last flew at night on 19 June 2004, and in actual or simulated instrument meteorological conditions, during 1998. His total instrument flight time was recorded as 32.4 hours.

The pilot was issued with a night VFR rating on 11 June 1998. There was no evidence that he had ever held an instrument rating. His three most recent flight reviews were completed on 29 March 2003, 18 November 2001, and 24 November 2000. They were logged as day flights, with no instrument or night flight recorded.

The pilot's family reported that he was well rested before the flight, was not affected by any illness and had never smoked cigarettes.

A person who spoke to the pilot while he was at Cobar reported that he said that it had been a busy day, and that he had not had any lunch, but was carrying some nuts and a drink on the aircraft.

Aircraft information

The aircraft was manufactured in the US in 1988 and was imported into Australia in the same year. At the time of the accident, it had accumulated about 2,868 flight hours. The aircraft was equipped and maintained in the instrument flight rules (IFR) category. It was fitted with a turbo-charged, piston engine which had accumulated about 180 hours since the last overhaul.

The aircraft cabin was not pressurised but was fitted with a supplemental oxygen system. The organisation that maintained the aircraft reported that the supplemental oxygen system tank was empty. There was no indication that the oxygen tank had been charged at Cobar.

A review of the aircraft's maintenance records revealed that the requirements of Airworthiness Directives (AD) RAD/43 and RAD/471 were due to be completed in July 2004 but had not been carried out. No other discrepancies were noted, and no defects had been recorded on the maintenance release.

The aircraft was fitted with an electrically driven standby vacuum system for providing pneumatic power to the gyroscopic instruments, and a Century 2000 autopilot system.

Meteorological information

Information provided by the Bureau of Meteorology indicated that the weather conditions in the Bokarina area at the time of the accident were benign. Smoke areas were forecast below 6,000 ft with visibility reducing to 4,000 m in smoke, and 1,000 m in thick smoke. The terminal area forecast for Maroochydore aerodrome (15 km north-north-west of Bokarina), issued at 1813, predicted visibility greater than 10 km and scattered cloud at 3,000 ft. None of the witnesses reported that smoke, cloud or haze affected their ability to see the aircraft.

The QNH2 recorded by the automatic weather station at Maroochydore at 2020 on the day of the accident was 1014 hPa.

On 15 August 2004 at the accident location, astronomical twilight occurred at 1846 and the moon set at 16373. Two cargo ships were located east of Maroochydore at the time of the occurrence, at least one of which was at anchor, and therefore displaying lights4. Several hours after the accident, witnesses observed two large ships moored east of Maroochydore which were displaying deck lights.

Wreckage and impact information

The wreckage was raised from the seabed on 28 August 2004 (Figure 2). Most of the aircraft was recovered, including the engine, fuselage, left wing, all three propeller blades and the propeller hub. The right horizontal stabiliser, right elevator, and parts of the right wing were not recovered.

An examination of the wreckage indicated that:

- The aircraft was banked right, and in a nose-down attitude of approximately 45 degrees when it struck the water.

- The nature of the damage to the engine crankshaft and the propeller blades was consistent with the engine delivering high power at impact.

- The frangible plastic drive shaft of the engine driven vacuum pump had failed under a sideways load. The drive shaft of the electrically driven vacuum pump was intact.

- Damage to the gyroscopes in the artificial horizon and directional indicator flight instruments was consistent with gyroscopic rotation at impact.

- The light globes in the artificial horizon and the directional indicator flight instruments were receiving electrical power at impact.

- The landing gear was retracted, and the wing flaps were extended about 10 degrees, at impact.

- The altimeter subscale was set at 1015.

- There was evidence of a short duration, post-impact fire.

Impact and saltwater corrosion damage precluded a determination of the serviceability of the automatic pilot system and its operational status during the final stages of the flight. None of the windscreen was recovered. There was no evidence in the recovered wreckage that the aircraft had struck a bird or a bat during flight.

The extent of airframe disruption and the missing parts of the right wing, horizontal stabiliser and right elevator prevented a comprehensive assessment of the functionality of the flight controls at impact.

Figure 2: Recovery of the main wreckage

Regulatory aspects

The pilot's night VFR rating authorised him to act as pilot in command of private or aerial work flights at night under the VFR. Civil Aviation Order (CAO) 40.2.2 detailed the flight tests and other requirements for the issue of a night VFR rating. The test requirements included recovery from unusual attitudes, basic turns, and straight and level flight, which were required to be conducted solely by reference to flight instruments. The CAO also required that training for the issue of a night VFR rating included at least one landing at an aerodrome 'that is not in an area that has sufficient ground lighting to create a discernible horizon'.

Once issued, a night VFR rating remained permanently valid. To exercise the privileges of the rating, a pilot needed to meet certain minimum recent experience requirements. There was no requirement for the holder of a night VFR rating to have any recent instrument flight time prior to conducting a flight at night 5.

Except during take-off, landing, or radar vectoring, the pilot of a night VFR flight was required to ensure than the aircraft remained at or above the calculated lowest safe altitude (LSALT) while further than 3 NM from the destination aerodrome. The minimum LSALT for the Bokarina area was 1,500 ft. Aircraft operating overpopulated areas were generally required to remain at or above 1,000 ft.

A pilot was required to satisfactorily complete an aeroplane flight review every 2 years. There were no published requirements or guidance material regarding theoretical knowledge or practical skills (such as flight conducted solely by reference to flight instruments) required to be demonstrated by pilots undergoing an aeroplane flight review.

Medical and pathological information

The pilot held a valid Class 2 Medical Certificate at the time of the occurrence. His medical records indicated that he had undergone a stapedectomy6 operation on his left ear about 22 years before the accident. He underwent a stapedectomy on his right ear on 11 April 2002 because of hearing loss. However, due to a post-operative decline in hearing and persistent balance problems, the prosthesis was removed on 24 April 2002. During two subsequent telephone conversations with the surgeon in June and July 2002, the pilot reported that he was still dizzy, couldn't look up and down quickly, and was still unsteady.

The pilot underwent a Class 2 aviation medical examination on 1 March 2004. The designated aviation medical examiner who performed that examination reported that the pilot had advised of no ongoing dizziness, disorientation, or other related problems.

A pathological examination did not identify any indication of a pre-existing medical condition that could have contributed to the development of the accident. It was not possible to establish when, or what, the pilot had last eaten.

Hypoxia

Hypoxia is a condition in which there is reduced oxygen supply to the body. Available oxygen decreases with increased altitude, such that at 12,000 ft, brain oxygen saturation is approximately 87%, compared with sea level saturation of 96%.

The investigation calculated that if the entire cruise segment of the flight had been conducted at 11,300 ft, the aircraft would have been at that level for almost 2 hours.

The US Federal Aviation Administration7 (FAA) recommended that pilots use supplemental oxygen when flying above 10,000 ft during the day and above 5,000 ft at night when the eyes become more sensitive to oxygen deprivation.

The Mooney M20K Aircraft Flight Manual stated that 'supplemental oxygen should be used when cruising above 12,500 feet. It is often advisable to use oxygen at altitude lower than 12,500 feet under conditions of night flying, fatigue, …'.

Civil Aviation Order (CAO) Part 20.4 paragraph 6.1 stated:

A flight crew member who is on flight deck duty in an unpressurised aircraft must be provided with, and continuously use, supplemental oxygen at all times during which the aircraft flies above 10,000 feet altitude.

An article8 in Flight Safety Australia magazine stated '[a]fter vision, the tissues most affected by hypoxia are those areas of the brain associated with judgement, self-criticism and the accurate performance of mental tasks'. An associated article9 in the same magazine indicated that the use of oxygen during night flight below 10,000 ft resulted in an increase in alertness and cognitive function, and a reduction in fatigue. Studies of the effects of exposure to altitudes between 10,000 ft and 15,000 ft have consistently shown small to moderate effects on human performance. Those effects included a reduction in night and peripheral vision, increased drowsiness, decreased response time, decreased short-term memory capacity, and poorer performance on complex and reasoning tasks.

The FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute Human Factors Research Laboratory in Oklahoma City, USA advised that restoration of a sea level atmosphere following exposure to hypoxic conditions caused rapid physiological recovery, but that cognitive recovery was slower.

Fatigue

Fatigue results from inadequate rest over a period of time, and leads to physical and mental impairment. The effects of fatigue include decreased short-term memory, slowed reaction time, decreased work efficiency, increased variability in work performance, a tendency to accept lower levels of performance and not correct errors. Not consuming food regularly is known to exacerbate the effects of fatigue.

Based on previous flights recorded in the pilot's logbook, the total flight time for the trip from Caloundra to Cobar and return to Caloundra would probably have been between 6.4 and 6.9 hours.

Stapedectomy

Stapedectomy involved a small risk of ongoing episodes of dizziness and hearing loss10. However, according to an article published in 1998 in the journal Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery11,

The FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] has always had the most experience with aircrew returning to flying duties after stapedectomy. The civilian track record is excellent with no reported cases of sudden incapacitating vertigo, sudden hearing loss, or other poststapedectomy related sequelae.

Spatial disorientation

Spatial disorientation describes an in-flight situation in which a pilot does not correctly sense the position, motion or attitude of the aircraft, and may be unable to tell which way is up. A pilot operating under the VFR determines the attitude of an aircraft by reference to the natural horizon or surface features. If these references are not visible, the pilot must use the flight instruments to determine the aircraft's attitude.

The risks of non-instrument rated pilots flying in conditions in which they are not able to orientate the aircraft by visual reference have been well known for over 50 years. During testing conducted on a group of non-instrument rated pilots, the average time before loss of control of the aircraft, after visual reference was lost, was 178 seconds12. An article titled 'Fatal Night Flight' in the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) magazine Flight Safety Australia (May-June 2005) stated that:

[v]isual disorientation is a distinct possibility on dark nights or away from areas of extensive ground lighting. Disorientation can be caused by sudden loss of visual reference such as when turning away from a well lighted area towards an area without ground lighting.

The article also stated that 'it is imperative that Night VFR pilots are competent and current in instrument flight'.

US FAA Advisory Circular 60-4A, Pilot's Spatial Disorientation, was published in 1983 and was intended to inform pilots of the hazards associated with disorientation caused by loss of visual reference with the surface. It included the following information:

Tests conducted with qualified instrument pilots indicate that it can take as much as 35 seconds to establish full control by instruments after the loss of visual reference with the surface.

Surface references and the natural horizon may at times become obscured, although visibility may be above visual flight rule minimums. The lack of natural horizon or surface reference is common on over water flights, at night, and especially at night in extremely sparsely populated areas, or in low visibility conditions.

Recent night VFR accident

On the evening of 17 October 2003, an air ambulance Bell 407 helicopter descended into the sea near Mackay, Qld. The ATSB investigation (200304282) was unable to determine, with certainty, what factors led to loss of control of the helicopter. The investigation considered that although the forecast weather conditions did not necessarily preclude flight under the night VFR rules, the lack of a visible horizon and surface lighting, and the pilot's limited instrument flying experience may have contributed to the accident. The investigation concluded that the circumstances of the accident were consistent with loss of control due to the pilot becoming spatially disoriented.

- AD/RAD/43 required a biennial altimeter and encoder check and AD/RAD/47 required a biennial transponder check.

- Sea-level atmospheric pressure.

- Information obtained from Geoscience Australia website http://www.ga.gov.au/nmd/geodesy/astro/

- Vessels over 100 m long and at anchor are required to display white lights at either end of the vessel and available working lights or equivalent to illuminate the decks.

- In contrast, the holder of an instrument rating was required to undergo an annual instrument flight test, and comply with flight and instrument approach recency requirements, in order to keep the instrument rating current.

- Stapedectomy is an operation to remove the fixed stapes [the third middle ear bone] and to replace it with a prosthesis. That allows sound vibrations to be transmitted properly to the inner ear for improved hearing. http://www.bcm.edu/oto/clinic/educate/stapled.html

- Federal Aviation Administration. 2003. Advisory Circular AC 61-107A Operations of Aircraft at Altitudes Above 25,000 feet MSL and/or Mach Numbers (MMO) Greater than .75.

- Brock, J. & Bencke, R. 1998. Hypoxia. Flight Safety Australia. Volume 3 Number 1. Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Canberra.

- Thom, A. 1998. Improved Performance. Flight Safety Australia. Volume 3 Number 1. Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Canberra.

- http://www.bcm.edu/oto/clinic/educate/stapled.html

- Thiringer, J.K. & Arriaga, M.A. 1998. Stapedectomy in Military Aircrew. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. Volume 118 Number 1. January 1998.

- Bryan, L.A., Stonecipher, J.W. & Aron, K. 1954. 180-degree turn experiment. University of Illinois Bulletin. 54(11), 1-52.

The investigation was unable to establish why the pilot lost control of the aircraft during a climbing turn while apparently returning to land at Caloundra aerodrome.

However, the following issues are considered to have been significant to the circumstances of the accident.

Aircraft altitude

The altitude of the aircraft as it passed over Bokarina was well below the minimum permissible for a night visual flight rules (VFR) flight, and was also below the minimum for a flight over a populated area. The aircraft's maximum altitude of 742 ft after it crossed the coast provided little margin for inadvertent height loss during the subsequent turn, and was evidently insufficient to allow the pilot to regain control of the aircraft.

Aircraft systems

There was no indication from the recorded radar information that the performance of the aircraft was abnormal. No radio transmission was heard from the pilot to indicate any problem with the aircraft.

Although one witness at Bokarina described the engine noise as abnormal, three other witnesses described the sound as normal and there was clear physical evidence that the engine was operating at high power at impact. There was also evidence that electrical power was being delivered to the lights, and that pneumatic power was being delivered to the gyroscopic instruments.

There was no evidence of a defect that could have affected the controllability of the aircraft. However, impact damage and the unavailability of some parts of the aircraft prevented a comprehensive assessment of the pre-impact serviceability of the flight control system.

Physiological and cognitive factors

The aircraft's recorded cruise altitude of 11,300 ft was above the altitude at which the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) required supplemental oxygen to be used, but was below the altitude above which oxygen should be used according to the aircraft flight manual.

By flying at 11,300 ft without supplemental oxygen, the pilot increased his risk of developing hypoxia. However, any hypoxic effect on the pilot's performance could not be quantified. The aircraft's steady track and descent profile prior to passing overhead Caloundra suggest that the pilot, probably assisted by the autopilot, was effectively controlling the aircraft. Further, any adverse physiological effects of mild hypoxia would have reduced before the final stages of the flight. However, it is possible that the pilot's cognitive function during the latter part of the flight was affected by earlier exposure to hypoxic conditions.

The duration of the day's flying, together with an inadequate food intake, could have caused the pilot to become fatigued.

Fatigue and hypoxia have been demonstrated to adversely affect areas of cognitive function such as response time, decision-making and risk assessment. Any decrement in cognitive function could have reduced the pilot's ability to identify the reduced level of safety associated with conducting a low-level flight at night over a populated area, and transitioning from an area of extensive ground lighting to an area where surface features and the natural horizon were difficult to discern. However, there was no means of determining if the pilot's cognitive function had been adversely affected. Nor was it possible to determine that if affected, it had not recovered to its normal state once the pilot was no longer exposed to hypoxic conditions.

The pilot's reported difficulties with balance following the April 2002 stapedectomy and subsequent removal of the prosthesis were consistent with expected side-effects of the operations. While these difficulties persisted for some months after the operation, the available evidence indicated that the pilot was not affected by dizziness or balance problems in the months preceding the accident.

Spatial disorientation

The forecast weather conditions did not preclude night VFR flight, and witness reports indicated that there was no reduction in visibility due to smoke or cloud at the time of the accident. The pilot's attention was probably directed outside the cockpit as he positioned the aircraft to fly over his home. Extensive ground lighting associated with the populated Sunshine Coast area would have provided him with good surface and horizon reference during that period. However, after the aircraft turned east, it was heading towards an area of no surface lighting (other than that provided by one or two large ships), and minimal celestial illumination. Consequently, surface features and the natural horizon would have been difficult to discern. Those conditions required that the pilot transition to flight by reference to the aircraft instruments.

The pilot's recorded night flight time indicated that he satisfied the recency requirements for night VFR. Further, the pilot was flying a familiar aircraft, which was suitably equipped (including a standby pneumatic power source) and maintained for instrument flight. However, the pilot had not demonstrated competence in flight solely by reference to instruments since 1998. The Federal Aviation Administration Advisory Circular 60-4A indicated that even qualified instrument pilots can take up to 35 seconds to complete the transition from visual to instrument flight. If the pilot did not achieve a rapid and complete transition to instrument flight during the climbing turn, it is likely that he would have experienced the effects of spatial disorientation.

Because there was no regulatory requirement that the pilot's recurrent aeroplane flight reviews include night VFR or instrument flight, his level of recent competence could not be assessed. The pilot's ability to transition to flight solely by reference to instruments may have been adversely affected by various factors, including a lack of recent experience in instrument flight, possible residual effects of hypoxia, fatigue, and/or a distraction in the cockpit. If the pilot's attention was directed elsewhere, he may not have initially recognised that the aircraft was descending, or the degree to which it was turning after it crossed the coast.

The ability to maintain visual reference with surface features and the natural horizon at night is not assured, even in meteorological conditions that satisfy the night VFR requirements. Consequently, as the Flight Safety Australia (May-June 2005) article advised, it is imperative that night VFR pilots are competent and current in instrument flight. Completing an aeroplane flight review and satisfying the night VFR requirements may not sufficiently reduce the risk of spatial disorientation of a pilot during night VFR operations.

Conclusions

The circumstances of the accident are consistent with a loss of control due to the pilot becoming spatially disoriented after flying into an area of minimal surface and celestial illumination. Physiological and cognitive factors may have contributed to the development of the accident. However, the factors that contributed to the aircraft descending into the water could not be conclusively established.

This accident highlights the need for night VFR pilots to manage the risk of spatial disorientation in dark night conditions by maintaining proficiency in instrument flight.

Previous recommendation

On 23 October 2002 the ATSB issued the following recommendation as a result of a fatal accident at night near Newman, WA, (ATSB Investigation BO/200100348):

Recommendation R20020193

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau recommends that the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) review the general operational requirements, training requirements, flight planning requirements and guidance material provided to pilots conducting VFR operations in dark night conditions.

On 13 December 2002, CASA responded to the recommendation as follows:

CASA acknowledges the intent of this Recommendation. As part of the proposed CASR [Civil Aviation Safety Regulations] Part 61, CASA is developing the requirements for night VFR ratings which will be based on the existing Civil Aviation Order CAO 40.2.2. In addition, a draft competency standard for night visual flight operations has been developed for inclusion in the proposed CASR Part 61 Manual of Standards. CASA plans to publish a Notice of Proposed Rule Making [NPRM] in relation to this matter in March 2003.

During July 2003, CASA published NPRM 0309FS Flight Crew Licensing and Draft Part 61 Manual of Standards [MOS]. The draft MOS included a requirement for a periodic flight review of night flying competencies. On 24 November 2004, the Chief Executive Officer of CASA issued two directives related to the regulatory reform process. As of March 2005, CASA was working on the processes necessary to apply the directives to the development of new CASR parts, including Part 61. In a letter to the ATSB dated 6 January 2006, CASA advised that the proposed CASR Part 61 would require night VFR rating holders to undergo flight reviews covering night and instrument flying, in addition to structural changes to the night VFR rating. CASA advised that Part 61 could be completed in the second half of 2006.

During March 2005, the ATSB issued Aviation Safety Investigation report BO/200304282 on the fatal night accident involving a Bell 407 helicopter, registered VH-HTD, which occurred off Cape Hillsborough, Queensland, on 17 October 2003. The report stated that CASA had advised that they intended to issue a CAAP (Civil Aviation Advisory Publication) to clarify safety guidelines for night VFR operations. In a letter to the ATSB dated 6 January 2006, CASA advised that the Night VFR CAAP was in the final stages of preparation, and it was intended that it would be published in the first quarter of 2006. The CAAP would include competency standards for night and instrument flying.

CASA has also advised that copies of a night VFR-related 'Briefing in a Box' were distributed to flying schools in March 2006. The briefings included safety material on night flying and were intended to assist flying instructors and flying schools in providing appropriate training to night VFR pilots.

Appendix A: Radar data relating to Mooney M20K VH-DXZ

| Time (EST) |

Altitude (ft AMSL) |

Groundspeed (kts) |

Explanatory notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014:01 | 1440 | 189 | |

| 2014:04 | 1440 | 189 | |

| 2014:08 | 1340 | 183 | |

| 2014:12 | 1340 | 183 | |

| 2014:15 | 1240 | 183 | |

| 2014:19 | 1240 | 183 | |

| 2014:23 | 1140 | 183 | Overhead Caloundra |

| 2014:26 | 1240 | 183 | |

| 2014:30 | 1240 | 183 | |

| 2014:34 | 1342 | 183 | |

| 2014:38 | 1342 | 179 | |

| 2014:41 | 1342 | 177 | |

| 2014:45 | 1342 | 185 | |

| 2014:49 | 1242 | 179 | |

| 2014:52 | 1242 | 165 | |

| 2014:56 | 1242 | 176 | |

| 2014:59 | 1142 | 172 | |

| 2015:03 | 1142 | 172 | |

| 2015:07 | 1042 | 182 | |

| 2015:11 | 1042 | 182 | |

| 2015:14 | 1042 | 182 | |

| 2015:18 | 1042 | 182 | |

| 2015:22 | 942 | 182 | |

| 2015:25 | 942 | 182 | |

| 2015:29 | 842 | 182 | |

| 2015:33 | 842 | 182 | |

| 2015:37 | 742 | 182 | |

| 2015:40 | 742 | 183 | |

| 2015:44 | 642 | 183 | |

| 2015:48 | 642 | 183 | |

| 2015:51 | 542 | 185 | |

| 2015:55 | 542 | 179 | |

| 2015:59 | 442 | 189 | Minimum recorded altitude |

| 2016:02 | 542 | 185 | |

| 2016:06 | 642 | 186 | |

| 2016:10 | 742 | 183 | |

| 2016:13 | 642 | 173 | Last valid radar return |