Executive summary

What happened

On 26 May 2024, a Cessna T210M, registered VH-MYW, was prepared for flight at Maitland Airport, New South Wales. The pilot planned to ferry the aircraft to Bankstown Airport, where the aircraft was to undergo maintenance. There was a pilot and one passenger on board.

During the approach, the engine stopped and while looking for a suitable landing place, the pilot saw a taxiway on the airport and decided to aim for that. To successfully reach the airport, the pilot elected to leave the flap retracted and gear up. This was done to reduce drag and achieve maximum glide range. Once the aircraft was assured of a landing on the airport, the gear was lowered. However, it did not successfully lock into place due to the limited time available before touchdown. The aircraft landed wheels-up resulting in minor damage and both occupants were uninjured.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB determined that, while the aircraft departed with sufficient fuel to complete the intended flight, it is likely that the amount of fuel reduced to a level that, in combination with unbalanced flight approaching Bankstown Airport, resulted in the engine being starved of fuel.

The ATSB also determined that the pilot's decision to carry non-essential crew placed the additional occupant at unnecessary risk of injury.

Safety message

Fuel starvation occurrences can often be prevented by conducting thorough pre-flight fuel quantity checks combined with inflight fuel management. Pilots are reminded to check fuel quantities prior to departure using a known calibrated instrument such as a dipstick. In addition, comparing the expected fuel burn with actual fuel remaining after a flight, will give a validated fuel burn for the aircraft and ensure the measuring equipment is accurate. Pilots should familiarise themselves with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Advisory Circular AC 91-15v1.1 Guidelines for aircraft fuel requirements, which provides further guidance for in‑flight fuel management.

Practising forced landings from different altitudes under safe conditions can help pilots prepare for an emergency situation, should one arise. Some components of the aircraft such as flap and gear, increase drag and reduce the glide range. Being familiar with emergency checklists and your aircraft’s systems will assist in an emergency when identifying and managing an engine failure.

The investigation

The occurrence

At 1313 local time, with the left fuel tank selected for take-off, the aircraft departed from runway 23[1] and tracked south. The pilot reported that about 4 minutes into the flight (while passing abeam Cessnock) they selected the fuller right tank, which they thought would reduce workload when entering Bankstown airspace. The aircraft entered the Visual Flight Rules (VFR) route[2] between Brooklyn Bridge and Prospect Reservoir at 1336 at approximately 2,000 ft.

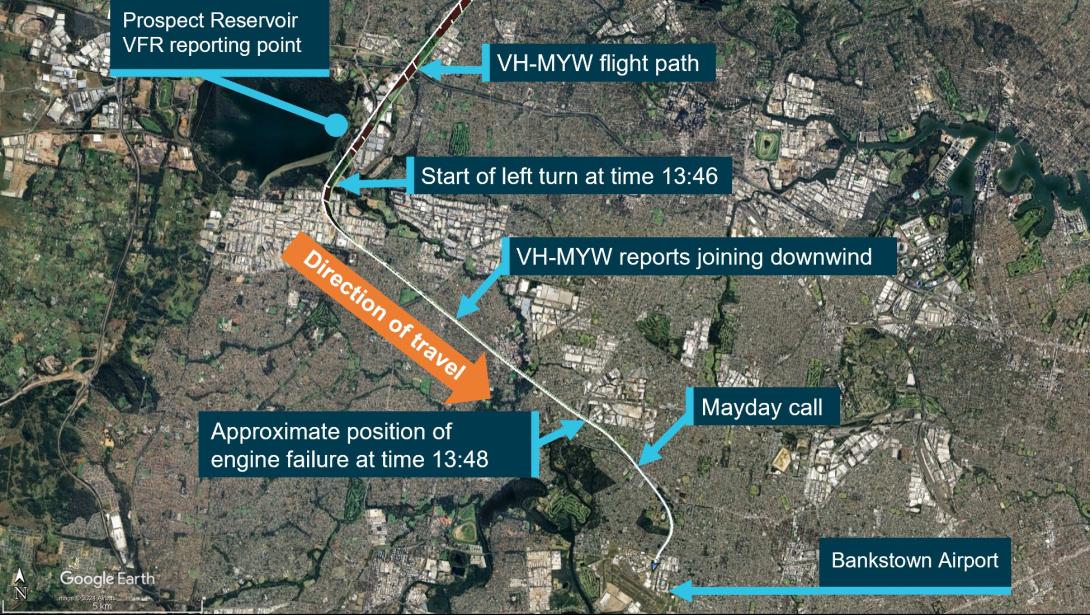

Figure 1: Sequence of events

The image shows the sequence of events leading up to and during the forced landing, it highlights relevant places and reference times.

Source: OzRunways flight data overlay on Google Earth.

The aircraft arrived overhead Prospect Reservoir at 1346 (Figure 1) and the aerodrome controller (ADC) instructed VH-MYW to maintain 1,500 ft and join the downwind leg of the circuit for runway 29R. An approximate 25° angle of bank turn was conducted to track toward a downwind join for runway 29R.

At 1347, the pilot reported joining downwind for 29R and the ADC instructed them to maintain 1,500 ft and provided them with updated Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS) [3] information ‘Foxtrot’. The pilot confirmed receipt of the new information by reading back the new QNH.[4]

The pilot recalled that, at about the time of that radio transmission, with the aircraft about 4.5 km north-west of Bankstown Airport, the propeller RPM increased, and they felt a braking sensation. They recalled that, in response they attempted to reduce drag on the propeller, changed fuel tank selection and briefly selected the electric fuel boost pump to ON. They then aimed to maintain glide speed while looking for a place to land.

At 1348, the pilot transmitted a MAYDAY call on the Bankstown Tower radio frequency stating they were having engine problems. The ADC advised that all runways were available, and they could track as required. The ADC continued to coordinate traffic to assist VH-MYW.

The pilot reported that while they were looking for a place to conduct a forced landing, they saw a taxiway on the airport and decided to try to land there. They advised that, during the approach the aircraft clipped the top of a tree and they raised the aircraft’s nose at the last minute to avoid a building on the airport perimeter. They decided not to deploy landing gear or flap until they were assured of reaching the airport.

At 1350, a helicopter operating in the area, reported that the aircraft had landed at the intersection of taxiway November 1 and taxiway Lima.

Both occupants of the aircraft were uninjured, and the aircraft sustained minor damage.

Context

Pilot

The pilot held a private pilot licence (aeroplane) issued in 2014 with a single‑engine class rating. They were appropriately endorsed to fly the Cessna 210 with design features for manual propeller pitch control and retractable undercarriage. The pilot also held a current class 2 aviation medical certificate.

They had accrued a total flight experience of approximately 222 hours, of which 15 hours were on the Cessna 210. In addition, they had previously flown other aircraft in this range including the Cessna 206 and Cessna 177. The pilot’s licence showed an entry for a single‑engine flight review conducted on 31 May 2023.

Weather

At the time of the incident, the Automatic Terminal Information Service information ‘Foxtrot’ was current, which indicated CAVOK[5] conditions, temperature 22°C, wind direction variable at 5 kt, and runway 29R in use for arrival and departures.

Aircraft

The aircraft was a Cessna Aircraft Company T210M manufactured in 1978 and issued serial number 21062277. It was powered by a fuel‑injected Continental Motors Inc TSIO-520-R piston engine driving a 3‑bladed, constant‑speed McCauley Propeller.

The aircraft was purchased from South Africa where it was previously registered as ZS-MYV and was shipped to Australia where it was reassembled and placed on the Australian register on 19 March 2021 as VH-MYW.

Maintenance

The aircraft was issued a maintenance release in November 2022 for private operations however, this expired in November 2023. At the time of the incident the aircraft was being ferried to Bankstown for completion of the maintenance required to return the aircraft to service.

As the maintenance release had expired, a special flight permit (SFP) was issued for the purpose of completing this ferry flight. The SFP was issued by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) on 14 May 2024. The permit expired on 31 May 2024 and was subject to the following conditions:

- Essential operating crew only to be carried.

- Daily inspection and flight times are to be recorded on the Maintenance Release.

- Day VFR, non-commercial operation by the most direct route practical and permitted by weather.

- Operation shall be conducted in accordance with the approved flight manual / cockpit placards for the aircraft.

- A copy of this SFP to be carried on-board and filed with the aircraft logbooks.

The permit also stated the flight was permitted to depart Maitland and arrive at Bankstown.

The last daily inspection signed on the aircraft maintenance release was completed on 2 November. The pilot advised that they had completed the daily inspection prior to the flight, but this was not recorded on the maintenance release.

The aircraft maintenance release also carried 2 endorsements for defects. These included the wing flaps not extending equally and hail damage. The flap defect was addressed by a third party, however, the hail damage was assessed by the aircraft owner in accordance with the CASA Airworthiness Bulletin 51-010 Assessment of hail damage.

Airworthiness Bulletin 51-010 recommended having a person who was appropriately qualified under Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 21.M to inspect the aircraft.

The pilot reported the aircraft had a tendency to fly right wing down. There was insufficient evidence available to the ATSB to determine whether either of the aircraft defects contributed to the flight characteristics described by the pilot.

Aircraft systems

Trim

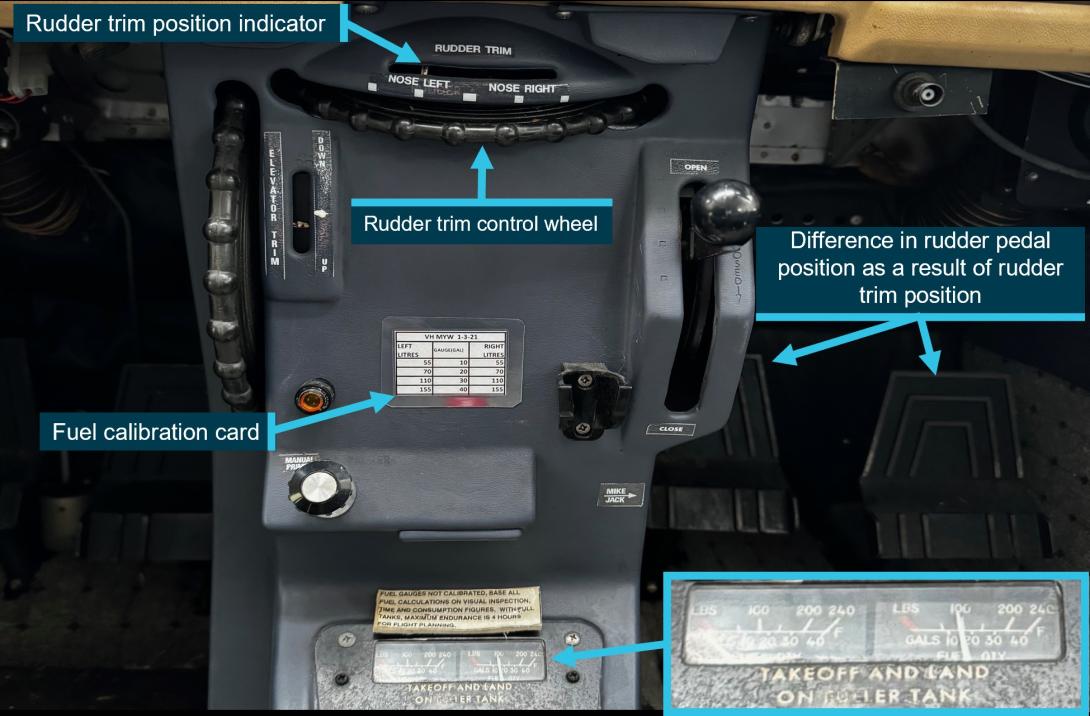

The aircraft was fitted with elevator and rudder trim. Rudder trimming was accomplished via a wheel mounted in the cockpit (Figure 2). Setting the rudder trim left of centre would result in the aircraft maintaining the nose left of the flight path and remaining in that position until the wheel was manipulated, or the rudder pedals were manipulated. To maintain the desired track with that trim configuration, the aircraft would need to be flown in an uncoordinated state with the right wing low.

The aircraft’s pilot operating handbook stated:

Unusable fuel is at a minimum due to the design of the fuel system. However, when the fuel tanks are ¼ full or less, prolonged uncoordinated flight[6] such as slips or skids can uncover the fuel tank outlets, causing fuel starvation and engine stoppage. Therefore, with low fuel reserves, do not allow the airplane to remain in uncoordinated flight for periods in excess of one minute.

Cessna advised this was originally added to the Cessna 210 model D owner’s manual and was carried through as the aircraft developed into different models. Cessna did not have the available data to assess the likelihood of uncoordinated flight contributing to fuel starvation.

The pilot stated the rudder trim had been set left of centre since the aircraft was re‑assembled in Australia and that the trim wheel was not manipulated in flight.

Figure 2: Aircraft control pedestal post-incident.

The image shows the fuel gauge level and the rudder trim. The image was taken on 6 June 2024, several days after the incident. However, the person responsible for recovering the aircraft stated, no fuel was added prior to this photo and the trim was set as found on the day of the incident.

Source: Engineer responsible for aircraft recovery.

Fuel system

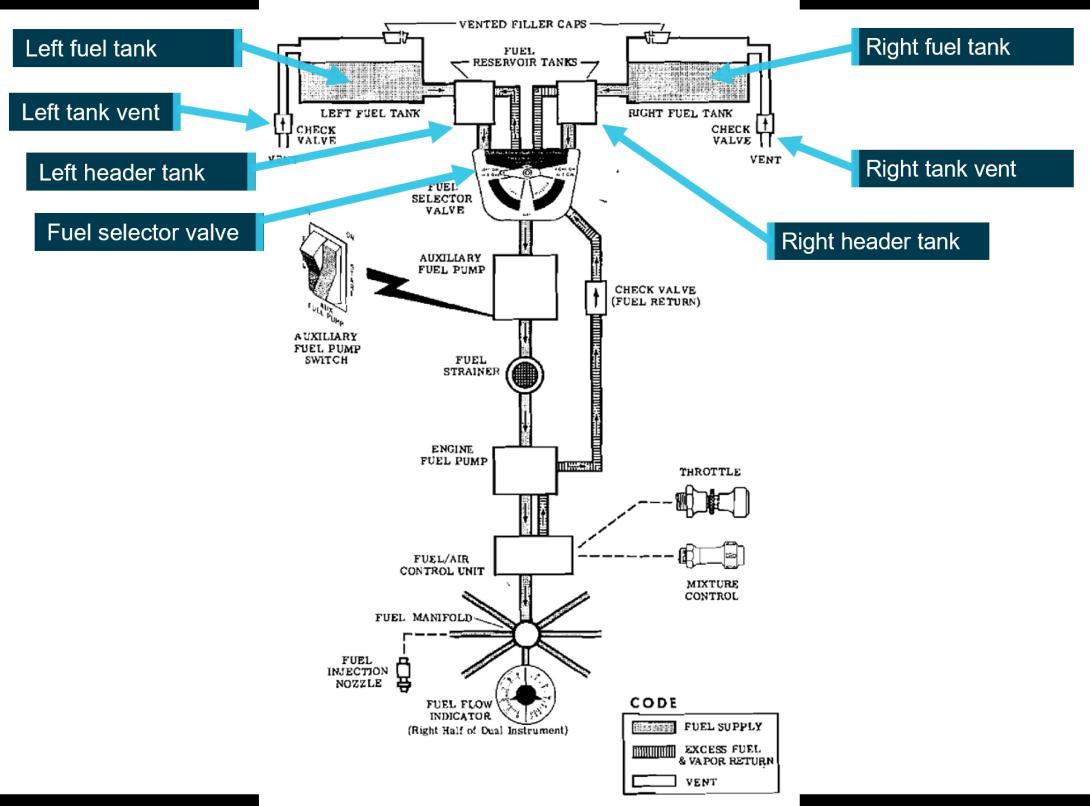

The Cessna 210 fuel system consists of a main fuel tank located in each wing. Each tank capacity is 171 L, of which 169 L is usable fuel. Each tank gravity fed a smaller fuel reservoir tank of approximately 1.9 L through fuel collector ports, which were located at the forward and aft inboard side of the main fuel tank (Figure 3Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3: Cessna 210M fuel schematic

Source: Cessna 210M pilot operating handbook, annotated by the ATSB

The fuel selector valve had 3 positions – left, right, and off – and so fuel could only be drawn from either the left or right tank. Cessna advised that at a low cruise power setting, if no fuel was being fed to the smaller fuel reservoir tank, it could supply fuel to the engine for between 1.5–3.5 minutes. The pilot advised that, at the time of the power loss the fuel selector was selected to the right fuel tank.

The fuel system has an engine-driven fuel pump and an auxiliary fuel pump, which is electrically driven. The pilot operating handbook states the following:

If it is desired to completely exhaust a fuel tank quantity in flight, the auxiliary fuel pump will be needed to assist in restarting the engine when fuel exhaustion occurs.

Cessna stated that during testing, the electric auxiliary fuel pump was required to operate for 4 seconds to restart the engine.

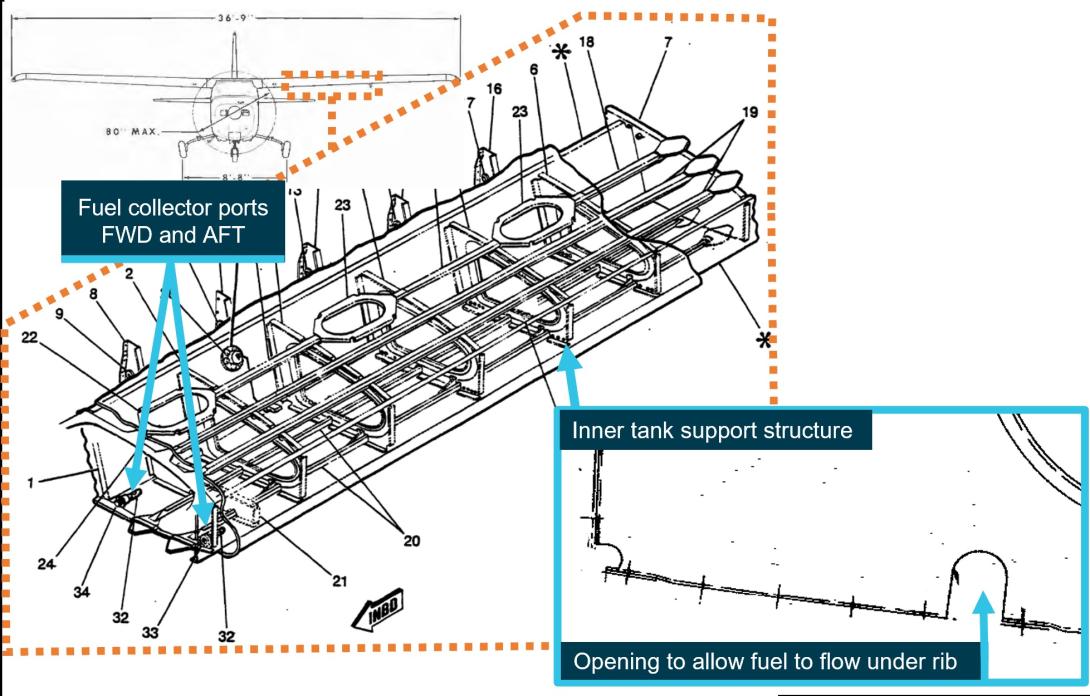

Figure 4: Fuel tank design

The above image shows the location of the fuel collector ports and the openings that are located in the rib support structure. The fuel cell image shown is for later serial numbers of the Cessna 210. However, it is the most descriptive image of fuel collector ports. Further images provided by Cessna show the aft collector port is located in a similar location to the above image.

Source: Cessna 210 illustrated parts catalogue model 210 & T210 series 1981–1986, annotated by the ATSB.

The fuel tank design included an internal rib support structure (Figure 4). Each rib had an enlarged centre opening for fuel to freely flow through the tank, with small openings at the base of each rib, ensuring useable fuel could not become trapped. Cessna stated, ‘The small, if any, amount of fuel caught behind any structure would be part of the unusable fuel level determined during certification.’

Propeller

A control lever was used to set aircraft RPM by changing the propeller blade pitch. When the control lever is pushed inward, the propeller increases RPM (low blade pitch). When the control lever is pulled outward, the propeller RPM decreases (high blade pitch). This is achieved by a propeller governor which relies on engine oil pressure to move the propeller toward a high blade pitch (low RPM).

The combination of an internal spring and centrifugal force, twists the blades toward a low pitch (high RPM) setting when oil pressure at the propeller hub is relieved.

Engine Failure During Flight checklist

The pilot operating handbook provided the following checklist to be conducted in the event of an engine failure during flight:

- airspeed – 85 [kt indicated airspeed] KIAS

- fuel quantity – check

- fuel selector valve – fuller tank

- mixture – rich

- auxiliary fuel pump – on for 3-5 seconds with throttle ½ open; then off

- ignition switch – both (or start if propeller is stopped)

- throttle advance slowly.

Flight data

The ATSB obtained flight data from an electronic flight bag (EFB) used by the pilot. The data provided aircraft position, time, altitude, and ground speed.

The flight data was analysed by the ATSB to obtain the approximate position when the engine stoppage occurred. This was determined to be at 1348 as there was a significant reduction in ground speed at that time.

Flight planning and fuel usage

The pilot reported that during the cruise, the manifold pressure was set near the top of the green (approximately 25 inches) and RPM at 2,200. A fuel flow reading was noted by the pilot of 14 gallons per hour (53 L/hr).

The pilot advised that they normally dipped the tank during the pre-flight inspection using the aircraft’s fuel dipstick. During the pre-flight they estimated 150 L of fuel on board, 60 L in the left tank and 90 L in the right tank (see the section titled Fuel system). Using that fuel quantity and recorded flight data, Table 1 details the expected consumption throughout the flight.

Table 1: Estimated fuel burn based on flight data

| Sector | Start time |

Block time (min) |

Estimated fuel burn (L) at 53 L/hr | Total | Comments | |

| Departing Maitland | 1313 | 0 | 5 | 145 | Pilot stated, they departed on left tank (5 L allowed for taxi) | |

| Abeam Cessnock | 1317 | 4 | 4 | 141 | Climbing phase, fuel burn was likely higher than 53 L/hr. | |

| Near Warnervale | 1325 | 8 | 8 | 133 | Pilot stated, at approximately overhead Cessnock, they swapped to right fuller tank. | |

| Brooklyn Bridge | 1336 | 11 | 10 | 123 | ||

| Prospect Reservoir | 1346 | 10 | 9 | 114 | ||

| Estimated engine stop | 1348 | 2 | 2 | 113 | ||

| Total | 35 | 38 | Totals have been rounded up |

Post-incident inspection

The ATSB did not attend the site. A video of the aircraft, provided by 9News Australia showed fuel leaking from the right fuel tank vent. The aerodrome operator who attended the incident site stated that the fuel which leaked from the vent was no more than 2–4 litres, of which most was funnelled into a jerrycan. While the ATSB could not verify how long the fuel was leaking, based on the observations of the aerodrome operator, it was unlikely to have significantly affected the amount of fuel in the tank. There was no evidence of fuel leaking from the left tank.

Figure 5: Fuel leak from right tank vent

Source: 9News Australia

The aircraft was recovered, and an initial inspection was completed. The fuel level was checked using the on-board fuel gauges and dipstick. The left tank was estimated to hold between 0–5 L and the right tank was estimated between 40–50 L.

The aircraft’s damaged propeller was removed, and a suitable test propeller was fitted to the aircraft. The engine was started and was able to draw fuel from the remaining fuel in both tanks, the test continued for approximately 5 minutes on each tank. However, high power settings similar to in‑flight conditions were not tested.

The aircraft had undergone a fuel calibration and the placard above the fuel gauges was no longer relevant however, it was not removed (Figure 2). The placard was not considered to have contributed to the incident as the fuel on board was likely less than the 4 hours stated on the placard. The onboard fuel dipstick used was labelled C210 dipstick and was marked with the aircraft’s previous registration, ZS-MYV.

Related occurrences

Fuel management and fuel starvation incidents and accidents continue to occur with single and twin-engine aircraft. Examples of other ATSB investigations of similar occurrences include:

- Fuel starvation and forced landing involving Piper PA-31-350, VH-HJE, 11 km south of Archerfield Airport, Queensland, on 7 April 2023 (AO-2023-017)

- Fuel starvation and ditching involving Piper PA-28, VH-FEY, 15 km north-west of Jandakot Airport, Western Australia, on 20 April 2023 (AO-2023-021)

- Fuel starvation and forced landing involving Pilatus Britten-Norman Islander BN2A, VH-WQA, Moa Island, Queensland, on 3 October 2022 (AO-2022-046).

Safety analysis

The pilot reported that, during approach to Bankstown Airport, they noted an increase in propeller RPM and could not maintain altitude. This behaviour was consistent with an engine failure, with the associated loss of oil pressure resulting in the propeller moving to a finer pitch (increased RPM). The post-incident aircraft inspection did not identify an engine malfunction, and the engine was able to run at low power on the remaining fuel in both tanks. As there was no evident malfunction of the engine, the most probable reason for the inflight power loss was fuel starvation.

The pilot reported that the aircraft departed with 90 L in the right tank and 60 L in the left tank (150 L total). They also advised the right tank was selected for most of the flight. If this was the case, there should have been approximately 61 L in the right tank and 51 L in the left tank. However, given the total fuel on board after the incident occurred (maximum 59 L), it was unlikely that approximately 91 L was burnt during the 35-minute flight. Therefore, it was unlikely that the amount of fuel the pilot stated was on board at the commencement of the flight was actually in the aircraft. Significantly however, there was sufficient total fuel on board for the flight.

The post-incident inspection revealed between 40–50 L remaining (which equated to approximately 1/4 full tank) in the right tank, with about 2–4 L reportedly leaking after the landing. The pilot operating handbook (POH) stated that if there was less than 1/4 fuel in the tank and the aircraft was in uncoordinated flight, the fuel pick-ups could uncover, and fuel starvation could occur.

The post-incident inspection also revealed between 0–5 L remaining in the left fuel tank. If the engine was being supplied from the left tank, during an uncoordinated left turn at Prospect Reservoir at 1346, it is possible the fuel drained away from the fuel pick-ups and the engine continued to draw fuel from the left header tank until 1348 when the engine stopped. This was consistent with Cessna’s advice that the header tank can supply fuel for 1.5–3.5 minutes at low cruise power.

In summary, irrespective of which tank was supplying the engine, the quantities of fuel remaining, when combined with the uncoordinated flight, were conducive to fuel starvation in accordance with the POH.

The pilot’s initial response during the emergency was largely focused on attempting to reduce drag created by the propeller, despite the aircraft not having this ability, and they did not complete the engine failure during flight checklist. If the checklist had been followed, the pilot would have increased the likelihood of restarting the engine in flight. During the extended period where the aircraft was resting on the ground and positioned right-wing low, it is likely the fuel remaining in the left tank drained into the left header tank. Even though this fuel was sufficient to run the engine at low power, it may not have been available during approach or sufficient for the power required in flight.

The pilot’s decision to minimise the aircraft’s drag during the glide, by keeping the gear up and flaps retracted, combined with managing the airspeed, resulted in the aircraft achieving the required performance to land safely inside the airport environment. However, due to the distance the aircraft needed to glide and obstacles that needed to be cleared, by the time the landing gear was selected down, there was not enough time to extend and lock in place before the aircraft collided with the ground resulting in a wheels-up landing.

Finally, the CASA special flight permit was issued for the purpose of ferrying the aircraft for maintenance. The conditions put in place were to minimise the consequences if an incident occurred during flight which was conducted outside of the normal aircraft operation. Although their reported purpose was to assist with navigation and radio communication, the pilot’s decision to allow a passenger to fly on board the aircraft unnecessarily exposed them to a risk of injury and consequently was another factor that increased risk.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the fuel starvation involving Cessna T210M, VH-MYW, 4 km north-west of Bankstown Airport, New South Wales, on 26 May 2024.

Contributing factors

- While the aircraft departed with sufficient fuel to complete the intended flight, low usable fuel quantities, in combination with probable uncoordinated flight approaching Bankstown Airport, resulted in the engine being starved of fuel.

Other factors that increased risk

- The pilot's decision to carry non-essential crew placed the additional occupant at unnecessary risk of injury.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- pilot

- aerodrome operator

- engineer responsible for aircraft recovery

- aircraft manufacturer and insurer

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- OzRunways recorded data

- video footage of the incident flight and other imagery taken on the day of the incident.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- pilot

- engineer responsible for aircraft recovery

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- aircraft manufacturer.

Submissions were received from the:

- pilot

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The CC BY 4.0 licence enables you to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon our material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. |

[1] Runway number: the number represents the magnetic heading of the runway. The runway identification may include L, R or C as required for left, right or centre.

[2] VFR route: A pre-defined laneway for aircraft traffic to remain clear of airspace and enter or exit high traffic areas such as Bankstown Airport.

[3] Automatic terminal information service: The provision of current, routine information to arriving and departing aircraft by means of continuous and repetitive broadcasts. ATIS information is prefixed with a unique letter identifier and is updated either routinely or when there is a significant change to weather and/or operations. See Automatic terminal information service (ATIS).

[4] QNH: the altimeter barometric pressure subscale setting used to indicate the height above mean seal level.

[5] Ceiling and visibility okay (CAVOK): visibility, cloud and present weather are better than prescribed conditions. For an aerodrome weather report, those conditions are visibility 10 km or more, no significant cloud below 5,000 ft, no cumulonimbus cloud and no other significant weather.

[6] Uncoordinated flight occurs when the aircraft skids or slips, this is most commonly associated with a turn, but a skid can occur when the ailerons and rudder are used in opposite directions during normal flight.