Executive summary

What happened

At about 1507, the crew commenced descent into Merimbula. As icing conditions were expected during the descent, the first officer (pilot monitoring) selected the engine and wing anti-ice ON. This also activated the ice speed system, which reduced the stall warning angle of attack activation angle.

At about 1514, the crew commenced a visual approach to runway 21 at Merimbula and selected flaps to 20 degrees for the landing. During the approach in turbulent conditions, the airspeed reduced and the stall warning activated.

The captain then re‑established the required approach flight path and speed, continued the approach and the aircraft landed without further incident. The aircraft was not damaged and there were no injuries during the incident.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that during an approach, in turbulent conditions, the captain reduced engine power to flight idle to avoid an inadvertent flap overspeed. Due to the autopilot mode active at the time, the reduced thrust resulted in a continuous reduction in airspeed that required pilot intervention to prevent activation of the stall warning system.

Due possibly to distraction associated with the windscreen wiper setting, the airspeed continued to reduce undetected by the crew until the stall warning activated at a higher than normal margin above the stall speed.

Safety message

The approach and landing phases of a flight can have substantially increased workload when compared to other phases. Effective monitoring of aircraft and approach parameters, including performance associated with autopilot modes, and management of any distractions during these phases is essential to ensuring that an approach is safely completed.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

At 1432 on 8 June 2023, a Regional Express Saab 340, registered VH-TRX (Figure 1), departed Sydney, New South Wales for an air transport flight to Merimbula, New South Wales with 3 crewmembers and 22 passengers on board.[1] The captain was acting as pilot flying, and the first officer as pilot monitoring.[2]

Figure 1: VH-TRX

Source: Ryan Hothersall

At 1507, the crew descended the aircraft from the cruising level of flight level 180.[3] As icing conditions were expected during the descent, the first officer selected the engine and wing anti-ice ON. This also activated the ice speed system, which reduced the stall warning angle of attack[4] activation angle and required the addition of 10 kt to the 116 kt landing reference airspeed[5] (see the section titled Approach speeds).

The crew elected to conduct a visual approach to runway 21 at Merimbula while using the required navigation performance instrument approach for lateral tracking to a 16 NM straight-in final approach leg.

During the approach, at 1517 with the autopilot engaged in the vertical speed mode,[6] the first officer selected flaps to 20° for the landing. At 1518:45, as the aircraft descended below 1,164 ft above mean sea level in turbulent conditions and at a speed of 143 kt, the captain reduced power to flight idle to prevent an inadvertent exceedance of the 165 kt maximum flap speed. A few seconds later, at 1518:54, speed reduced below 136 kt, the minimum speed for that segment of the approach (see the section titled Approach speeds).

The power remained at flight idle, and speed continued to reduce as the approach continued (Figure 2) with the engine anti-ice and ice speed systems selected on. The aircraft then entered a rain shower, and the captain asked the first officer to turn on the windscreen wipers. The first officer asked if they should be set to low or high and the captain asked for the high setting. The wiper activation was then delayed as the turbulence prevented the first officer from quickly making the required selection. At about the same time, with power still at flight idle, the aircraft encountered increased turbulence and at 1519:21, at a speed of 109 kt, the stall warning activated.

Figure 2: Approach flight path

Source: Google earth, annotated by ATSB

The captain responded to the stall warning by reducing the aircraft’s pitch attitude and increasing engine power and 4 seconds after the stall warning activated, speed increased above 116 kt. At 1519:29, speed increased above 126 kt and 5 seconds later increased above the minimum segment speed of 136 kt. The aircraft also descended below the desired approach path. The captain identified the low approach profile and reduced the descent rate to re‑establish the desired path.

The first officer then called for a missed approach to be conducted. The captain acknowledged the first officer’s call but elected to continue the approach because:

- the approach profile had been quickly re‑established

- the runway and visual approach guidance system[7] was in sight

- they assessed that a missed approach would take the aircraft ‘back up into the weather’.

At 1519:55, the aircraft descended below 300 ft above aerodrome level (AAL), the stabilised approach check height for the visual approach. At that time, the approach was stable and remained so until the aircraft landed at 1520:36. The aircraft was not damaged and there were no injuries during the incident.

Context

Crew details

The captain held an air transport pilot licence (aeroplane) and class 1 aviation medical certificate. The captain had over 20,000 hours of flying experience, of which over 13,000 hours were on the Saab 340.

The first officer held a commercial pilot licence (aeroplane) and class 1 aviation medical certificate. The first officer had 1,419 hours of flying experience, of which 172 hours were on the Saab 340.

The ATSB found no indicators that the flight crewmembers were experiencing a level of fatigue known to affect performance.

Stall warning system

The stall warning and identification system fitted to the Saab 340B included:

- 2 independent stall warning computers

- 2 angle of attack (AOA) sensors – one mounted on each side of the fuselage

- an aural alerting system

- a stick shaker device on each control column that provided a physical warning of an impending aerodynamic stall in the form of vibrations and an aural clacker sound when activated

- a stick pusher device that applied forward force to the control column to reduce aircraft AOA when a stall condition was identified

- a visual alerting system.

The aural alert system and stick shaker devices normally activated at 12.5° AOA while the visual alert and stick pusher activated at 19° AOA.

Operations in icing conditions

Airframe icing occurs when water droplets (cloud or liquid precipitation) at temperatures below their freezing point (supercooled) freeze on impact with aircraft surfaces. Icing conditions are only present in temperatures between 0°C and -40°C, with the highest risk of icing occurring between 0°C and -15°C. An accumulation of ice on an aircraft increases both drag and weight, reduces thrust and reduces the stall angle of attack (increases the aerodynamic stall speed). This results in smaller stall margins than for a clean (free of ice) aircraft.

The stall warning activation occurred 7 minutes after the aircraft descended out of icing conditions and, at that time, both flight crewmembers noted that the aircraft was free of ice.

Ice speed system

The ice speed system fitted to VH-TRX compensated for possible ice accumulation by lowering the stall warning stick shaker/aural alert activation AOA by about 6°. The visual alert and stick pusher activation AOA remained unchanged.

The system was activated by selecting either (or both) engine anti-ice systems on and was indicated by the illumination of a blue ICE SPEED push button on the instrument panel (Figure 3). Once activated, the ice speed system remained active even if the engine anti-ice system was subsequently selected off and needed to be deselected separately.

Figure 3: The flight deck of VH-TRX showing the ice speed system indicator

Source: Regional Express

The operator’s Flight Crew Operating Manual (FCOM) required that the ice speed system remain active for 5 minutes after leaving icing conditions or until the aircraft was free of ice, whichever occurred later. The manual also included the following caution:

Failing to increase reference speeds when the ice speed status light is illuminated reduces the margin to a stall warning indication. A stall warning may be triggered if the landing reference speed has not been corrected when the ice speed status light is illuminated.

Recovery from stall warning or stall

The FCOM for the SAAB 340 included the following procedure for recovery from a stall warning or stall:

The recommended procedure when recovering from a stall warning (stick shaker or natural buffeting) or stall in a clean or iced-up aircraft is to lower the nose approximately 5 degrees or as commanded by the stick pusher (if not restricted by proximity to ground), simultaneously apply Max power and if required roll the wings level.

This procedure also provided mandatory actions to be taken when a stall was identified:

In recovering from a low-level stall, or stall with gear or flap extended, apply standard go around procedures once a minimum of reference speed + 10 (+ 20 in icing) or stall/warning speed + 30kts is attained. Consider the possibility of a secondary stall.

Approach speeds

The base calculated reference speed for the approach was 116 kt. As the ice speed system was active, 10 kt was required to be added to the reference speed to provide the adjusted reference speed of 126 kt to be used by the crew for the landing.

For the final approach, until the 300 ft stabilisation check height, the crew was required to maintain a speed between 10 kt above the adjusted reference speed (136 kt) and 160 kt.

Meteorology

The approach was conducted in visual meteorological conditions and moderate turbulence.

At 1500, 19 minutes before the incident, the Bureau of Meteorology automatic weather station at Merimbula Airport recorded the temperature as 15° Celsius and the wind as 2 kt from 257° magnetic. Cloud cover was recorded as scattered[8] at 5,808 ft above mean sea level (AMSL), broken at 6,708 ft AMSL and overcast at 8,308 ft AMSL. Visibility was recorded as greater than 10 km in light rain.

Table 1: Merimbula Airport recorded wind observations

| Time | Wind direction | 1 minute wind speed (kt) | 1 minute wind gust (kt) |

| 15:05 | north-west | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| 15:06 | north-west | 2.9 | 4.1 |

| 15:07 | north-west | 2.9 | 4.1 |

| 15:08 | north-west | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| 15:09 | north-west | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| 15:10 | west-north-west | 4.1 | 5.1 |

| 15:11 | west-north-west | 6.0 | 7.0 |

| 15:12 | west | 8.0 | 9.9 |

| 15:13 | west | 11.1 | 14.0 |

| 15:14 | west | 9.9 | 13.0 |

| 15:15 | west | 8.9 | 13.0 |

| 15:16 | west | 8.0 | 9.9 |

| 15:17 | west | 8.9 | 12.1 |

| 15:18 | west-north-west | 6.0 | 7.0 |

| 15:19 | west-north-west | 7.0 | 8.9 |

| 15:20 | west-north-west | 6.0 | 7.0 |

| 15:21 | north-west | 5.1 | 7.0 |

| 15:22 | north-west | 7.0 | 8.0 |

| 15:23 | north-west | 5.1 | 7.0 |

| 15:24 | north-west | 5.1 | 6.0 |

| 15:25 | north-north-west | 5.1 | 6.0 |

At 1530, 11 minutes after the incident, the temperature was recorded as 14° Celsius and the wind as 6 kt from 297° magnetic. Cloud cover was recorded as scattered at 3,308 ft AMSL, scattered at 5,608 ft AMSL and scattered at 7,008 ft AMSL. Visibility was recorded as greater than 10 km in light rain.

Recorded data

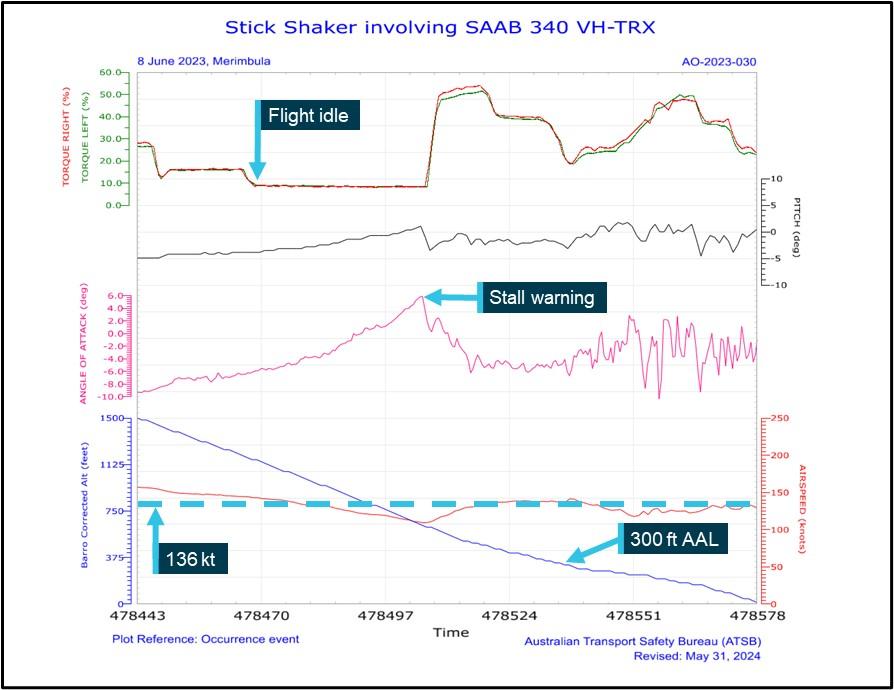

Analysis of flight data from VH-TRX’s flight data recorder showed that power was reduced to flight idle at 15:18:45, as the aircraft descended through 1,164 ft AMSL. Following the power reduction, the aircraft’s speed began reducing while the autopilot increased the aircraft pitch angle and wing AOA to maintain the selected descent rate. Nine seconds after the power reduction, speed reduced below 136 kt. A further 11 seconds later, speed reduced below 126 kt and 11 seconds after that, at 15:19:16, speed reduced below the base reference speed of 116 kt.

At 15:19:21, while descending though 636 ft AMSL and 34 seconds after power was reduced to flight idle, the speed slowed to 109 kt. The AOA increased to 5.9° and the stall warning activated for 1 second (Figure 4). At the same time the autopilot automatically disconnected.

Figure 4: Graphical representation of recorded flight data

Source: ATSB

Following the stall warning, the recorded angle of attack reduced by 5.6° within 2 seconds and power increased to about 50% torque within 4 seconds. At 15:19:35, 14 seconds after the stall warning, the speed increased above 136 kt and power began to be reduced to the normal approach power setting. The recorded data showed the descent rate reduced from the 830 ft per minute rate, recorded before the stall warning activation (with autopilot engaged), to about 450 ft per minute.

Audio data from the cockpit voice recorder was not available.

Decision to continue the approach

Following the stall warning activation, the first officer called for a missed approach to be conducted. The captain acknowledged the first officer’s call but elected to continue the approach.

The stall warning occurred when the aircraft was free of ice and at a height of 628 ft above the aerodrome elevation,[9] 328 ft above the stabilised approach check height of 300 ft AAL. The lowest speed recorded was 109 kt (27 kt below the minimum required speed), 21 kt above the calculated stall speed of 88 kt. Following the stall warning, the captain, acting as pilot flying, added sufficient power to increase speed above the minimum required for that phase of the approach.

The aircraft also descended below the required approach path. The captain recognised that the aircraft was low and commenced correcting it. As the aircraft descended below 300 ft AAL, it remained slightly below profile until regaining the approach path shortly after.

The actions defined in the operator’s FCOM procedure for recovery from a stall warning (see the section titled Recovery from stall warning or stall) were recommended and not mandatory. At low level, a missed approach was only mandatory in the case of an identified stall. Therefore, the captain’s actions did not contravene the operator’s procedures. Additionally, the operator’s procedures provided a mechanism for the first officer to escalate the situation if they disagreed with the captain’s decision to continue the approach.

The captain’s stated reason for the decision to continue was that the approach was restabilised, the runway and visual approach guidance system was visible, and a go-around would take the aircraft ‘back into the weather’. Therefore, the captain assessed that continuing the approach was the safest decision. The ATSB assessed that this decision was reasonable given the information available to the captain at the time and did not unduly increase risk to the flight.

Similar occurrences

In 2013, the ATSB research report Stall warnings in high capacity aircraft: The Australian context 2008 to 2012 identified that 245 stall warnings in high capacity aircraft had been reported between 2008 and 2012 in Australia. Almost all of those were low risk events of momentary duration and were responded to promptly and effectively by the flight crew to maintain control of the aircraft. However, there were also several higher risk incidents where stick shaker activation occurred on approach to land when aircraft were in a low speed, high AOA configuration. In these cases, the risk of a stall developing was increased by a lack of awareness of decreasing airspeed and increasing AOA prior to the stall warning, probably due to increased flight crew workload during this phase of flight. None of the reported occurrences resulted in an actual stall.

Safety analysis

During the descent and prior to the approach, the aircraft descended through icing conditions and the crew activated the engine anti-ice system. This also activated the ice speed system, which reduced the stall warning angle of attack activation angle. The approach was then commenced within 5 minutes of leaving icing conditions. Therefore, the ice speed system was still active as the approach commenced (as per the operator’s procedure). However, by the time of the occurrence the aircraft was operating in clear conditions and an ambient temperature well above freezing and there was no ice on the aircraft. This meant that the stick shaker/aural warning associated with an approaching stall was set to activate at an AOA of only 6° rather than the normal trigger AOA of 12.5°. That is, at a greater airspeed margin than normal above an actual (ice free) stall.

As the approach continued in turbulent conditions with the autopilot engaged, the captain, concerned that the turbulence may lead to an inadvertent exceedance of the flap limit speed, reduced power to flight idle and the aircraft speed started reducing. Due to the selected autopilot mode, the reduced thrust led to the aircraft pitch angle and wing angle of attack being automatically increased to maintain the selected descent rate. Significantly, this resulted in a further ongoing speed reduction that required pilot intervention to prevent activation of the stall warning system. While the power was selected to flight idle, the aircraft entered a rain shower and turbulence, likely associated with a gust front that was recorded passing over Merimbula Airport at about that time. At about that time, the captain asked the first officer to turn on the windscreen wipers followed by a brief discussion about the desired wiper setting.

The windscreen wiper setting discussion and subsequent minor delay in enacting the request possibly distracted the crew from effectively monitoring the airspeed and they did not identify that the speed had reduced significantly below the 136 kt minimum speed for that segment of the approach. This deceleration continued until the speed reduced to 109 kt and the stall warning system activated at the reduced ice speed system angle of attack.

The crew responded by recovering the aircraft, continuing the approach and landed the aircraft without further incident.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the stall warning activation involving a Saab 340, VH-TRX, 5 km north of Merimbula Airport, New South Wales on 8 June 2023.

Contributing factors

- During an approach, in turbulent conditions, the captain reduced engine power to flight idle to avoid an inadvertent flap overspeed. Due to the autopilot mode active at the time, the reduced thrust resulted in a continuous deceleration that required pilot intervention to prevent activation of the stall warning system.

- Due possibly to distraction associated with the windscreen wiper setting, the airspeed continued to reduce undetected by the crew until the stall warning activated at a higher‑than‑normal margin above the stall speed.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Regional Express

- the flight crew

- Bureau of Meteorology

- recorded flight data from VH-TRX.

References

- ATSB aviation research investigation report AR-2012-172, Stall warning in high capacity aircraft: The Australian context, Australia.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Regional Express

- the flight crew

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Submissions were received from:

- Regional Express

- the captain.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] The flight was operated under Civil Aviation Safety Regulations Part 121 (Air transport operations - larger aeroplanes).

[2] Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM): procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances; such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and the aircraft’s flight path.

[3] Flight level: at altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 180 equates to 18,000 ft.

[4] Angle of attack is the relative angle between the chord line of the wing and the approaching airflow.

[5] All further reference to ‘speed’ should be read as airspeed.

[6] In the vertical speed mode, the autopilot adjusted the pitch of the aircraft to maintain a selected vertical speed.

[7] Runway 21 at Merimbula was equipped with a precision approach path indicator (PAPI) lighting system.

[8] Cloud cover: in aviation, cloud cover is reported using words that denote the extent of the cover – ‘scattered’ indicates that cloud is covering between a quarter and a half of the sky, ‘broken’ indicates that more than half to almost all the sky is covered, and ‘overcast’ indicates that all the sky is covered.

[9] The threshold elevation of runway 21 at Merimbula was 8 ft.