Executive summary

What happened

On the morning of April 6 2023, a chartered GippsAero GA8 Airvan, registered VH‑TBU and operated by Shine Aviation Services, took off from Geraldton Airport to Rat Island aircraft landing area in the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, Western Australia. A pilot and 6 passengers were on board.

During the landing on runway 18, the aircraft did not stop before the edge of the island and tipped into shallow seawater. The pilot and passengers were uninjured. The aircraft was substantially damaged.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the aircraft was unstable during the approach due to excessive height and airspeed. During the landing, the aircraft floated for a significant time and touched down approximately halfway down the runway, with insufficient remaining runway to stop. While the pilot recognised opportunities to conduct a go-around when they determined they were not on the correct approach profile, this was not conducted.

Finally, the ATSB found that the pilot was possibly experiencing fatigue at a level known to affect human performance, due to a combination of restricted sleep and insufficient sustenance.

What has been done as a result

Shine Aviation Services has taken safety action to improve pilot landing and late‑stage go‑around training for their single‑ and multi‑engine piston aircraft. An increased oversight program has also been implemented to provide more regular mentoring for junior flight crew.

Safety message

This incident highlights how an unstable approach can contribute to the risk of a runway excursion. Pilots should be prepared to conduct a go-around if the stabilised approach criteria are not met. The later the decision to go-around is made, the more likely that additional hazards will be present for pilots to manage.

The investigation

The occurrence

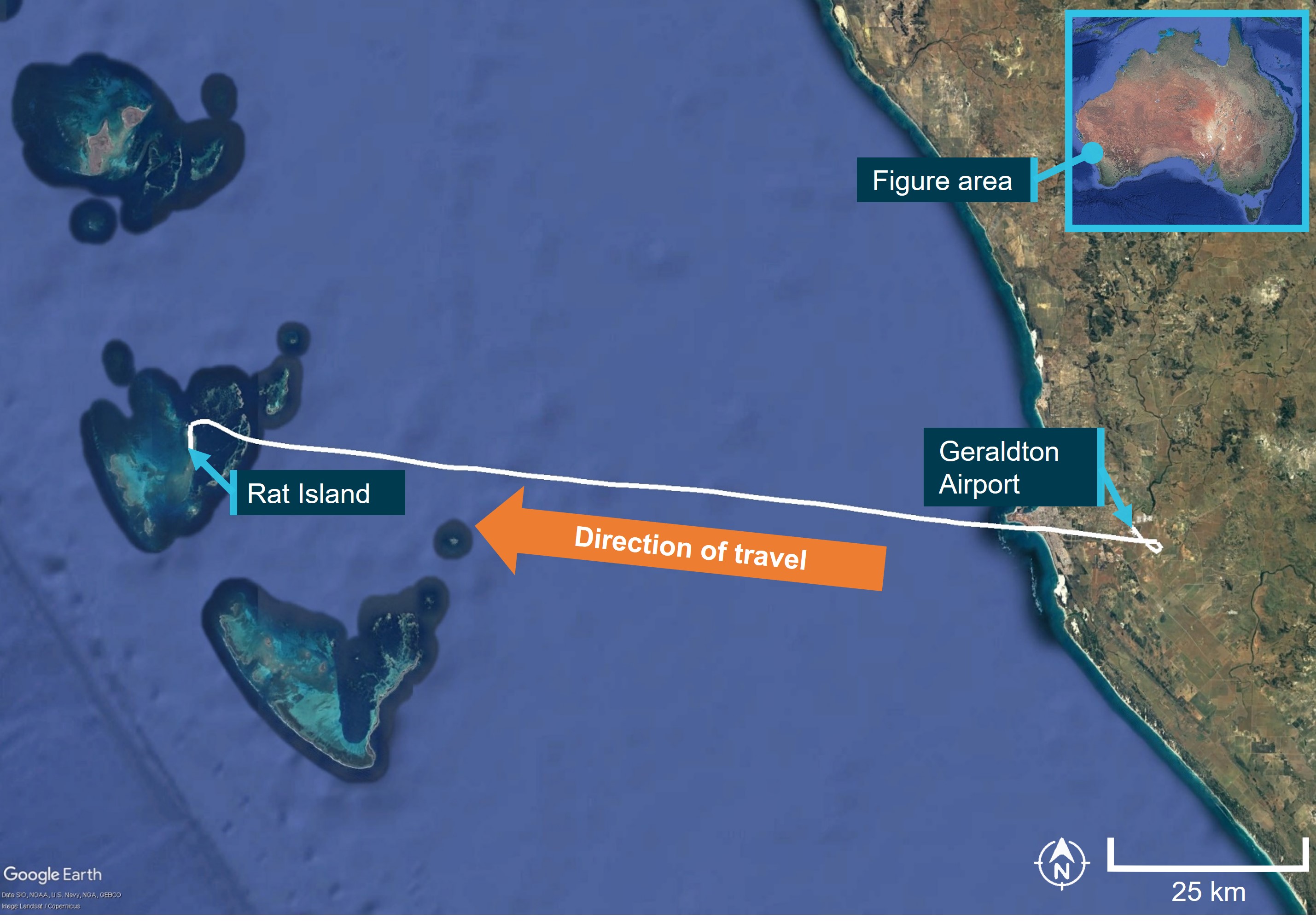

On 6 April 2023, a GippsAero GA8 Airvan registered VH-TBU and operated by Shine Aviation Services was being used on a chartered passenger flight. The aircraft departed Geraldton, Western Australia at 0814 local time on a flight to Rat Island in the Houtman Abrolhos Island chain, Western Australia (Figure 1). Onboard were the pilot and 6 passengers.

Figure 1: Flight track of VH-TBU

Source: Google Earth and flight track, annotated by ATSB.

After cruising at 2,600 ft, the aircraft approached Rat Island and joined an extended base leg of the circuit for runway 18.[1] The pilot made a left turn onto final and extended the flaps to 38°.[2] Coming out of the final turn, the pilot noticed that the aircraft was higher than normal. Consequently, they reduced the engine power to idle and lowered the nose of the aircraft to intercept the normal approach profile. The pilot advised the aircraft’s airspeed increased to approximately 85 kt at this stage, before reducing to a little higher than normal over the threshold (see the section titled Stabilised approach criteria).

During the landing, the aircraft floated significantly more than the pilot expected, with the aircraft touching down about 247 m beyond the threshold (Figure 2). The pilot recalled ‘jumping on the brakes’ as soon as they touched down, and then realised that the aircraft could not be stopped before the runway end. In response, they applied left rudder in an attempt to avoid entering the water in the overshoot. The aircraft traversed the runway overshoot area, coming to rest on the island’s edge, before tipping forward into shallow seawater at about 0841 (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Rat Island runway and flight path of VH-TBU

Source: Google Earth and flight track, annotated by ATSB.

Water entered the cockpit to about ‘shin-height’ and the passenger seated in the rear left seat opened the emergency exit upon recalling the instructions from the safety briefing. All 6 passengers evacuated the aircraft through the rear left door. The pilot evacuated through the left cockpit door, walking across the wing strut onto land (Figure 3).

Neither the pilot nor 6 passengers were injured during the landing or evacuation. The aircraft sustained substantial damage to the nosewheel, propellor, right landing gear and cargo pod, and remained partially submerged for several days before being airlifted back to Geraldton.

Figure 3: VH-TBU accident site

Source: Shine Aviation Services, annotated by ATSB.

Context

Pilot information

The pilot held a commercial pilot license (aeroplane) with an instrument rating, and a class 1 aviation medical certificate. They had a total of 789.7 hours flying experience, of which 157.4 hours were operating the GA8 Airvan. The pilot had experience flying a variety of single‑ and multi-engine piston aircraft during island operations. They had been flying for the operator for about 12 months and had flown to Rat Island many times.

The pilot had passed an instrument proficiency check (IPC) in February 2023 and operator proficiency check (OPC) in September 2022, which included satisfactory results in conducting a missed approach/go‑around. [3]

Aircraft information

The GA8 Airvan is a single engine aircraft manufactured by GippsAero[4] of Victoria, Australia. It is fitted with a Textron Lycoming IO-540-K1A5 piston engine and can seat up to 8 people, including the pilot. VH-TBU was manufactured and registered in 2002. It was owned and maintained by the operator.

The aircraft was maintained in accordance with the GA8 service manual and had a current maintenance release. The last periodic inspection was in March 2023, and the aircraft had accumulated about 3,256.7 total hours in service.

The aircraft’s maintenance records showed an open observation recorded 2 weeks prior to the occurrence that the pilot seat was difficult to adjust. Prior to the flight, the pilot had detected this and decided it would not affect their ability to control the aircraft. During the flight, the seat was set fully aft, 1–2 increments further back than the pilot’s normal seat position. They later observed that, with the seat further rearward than normal, they could not fully depress the brake pedals.

After the accident, the ATSB received photographs of the aircraft and identified evidence of previous low hydraulic fluid in the left brake master cylinder. This was recorded to have been topped up 3 weeks prior to the occurrence, after a report of sponginess [5] on the left brake. It was unclear if this was the case at the time of the accident, although evidence of wheel skidding was observed on the runway surface after this occurrence.

Rat Island aircraft landing area

Rat Island aircraft landing area (ALA) was managed by the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). It had one unsealed runway aligned 180/360° and was about 517 m long and 30 m wide, with no significant slope. The windsock was located at the northern end, and there was a 20 m rocky overrun area at the end of runway 18. DBCA reported that improvements had been made to the overrun surface area in August 2022. The airstrip was suitable for GA8 operations.

Meteorological information

Rat Island did not have a dedicated Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) weather station. Weather observations at North Island weather station, about 50 km north of Rat Island, showed that 10 minutes prior to the runway excursion, winds were 110°, varying between 9 to 13 kt.

The pilot reported that the conditions on Rat Island favoured runway 18 with a slight headwind, which was usual for this area. They were unable to recall the direction of the windsock, and it was not captured on the passenger video recording (see the section titled Recorded data). The runway was dry.

Stabilised approach criteria

The operator required that if a VFR aircraft was not stable by 500 ft above the touchdown point a go‑around was to be conducted. The following stabilised criteria was outlined in their policy and procedures manual:

- the aircraft is on the correct lateral and vertical flight path

- descent rate is less than 1,000 ft per minute

- bank angle is less than 10°

- the aircraft is in the correct landing configuration

- the aircraft is at approach speed (Vref to Vref +10) [6]

- power setting is appropriate for the configuration

- conditions landing checklist has been completed

The operator’s policy and procedures manual also stated:

The GA8 flight manual noted that for approach and landing:

The pilot reported being familiar with the stabilised criteria, and a general rule of thumb to conduct a go-around if the wheels had not touched down by the first third of the runway when using a shorter runway.

The standard approach into Rat Island for the GA8 at maximum take‑off weight was a standard approach angle of 7° at idle power. Pilots were instructed to employ a short-field landing to cross the threshold at a maximum airspeed of 70 kt, and upon touchdown, retract the flaps, applying firm brake application and back pressure on the control column to allow the full weight of the aircraft onto the runway for maximum braking effectiveness. Calculations for the distance required to land a GA8 aircraft with a 3 kt headwind indicated that from 50 ft overhead the threshold, it would need 410 m of runway to stop, including a ground roll of 170 m.

Recorded data

The operator supplied flight data and a passenger took a video recording of the landing and runway excursion on their mobile phone. This passenger was sitting in the front right seat, and primarily videoed in the direction of travel out the lower right corner of the windscreen. This information was used to conduct a flight path analysis of the approach and landing. The flight analysis revealed that from the start of the video recording to the 50 ft point on the approach, the average approach angle was about 10º.

At 50 ft altitude on final, and about 70 m from threshold, the aircraft was travelling at a groundspeed of 88 kt. At the runway threshold (about the landing aim point), the aircraft was about 21 ft above ground level (AGL) and was travelling at a groundspeed of 86 kt. After the flare, the aircraft floated for about 170 m, and touched down approximately 247 m beyond the threshold, travelling at a groundspeed of 77 kt. It was at this point that the pilot reported that the airspeed was slightly below the aircraft’s Vref speed of 70 kt. The aircraft exited the overrun area at a groundspeed of about 43 kt. Full flaps remained deployed during the landing sequence.

Work schedule

The pilot was rostered for a flight duty period (FDP) [7] between 0530–1800, with a split-duty rest period from 1000–1400 for sleep at home, which was 15 minutes commuting time away. They were to then sign on again at 1530. They had flown a return trip from Geraldton to East Wallabi Island earlier that morning, and had flights scheduled at 1600 and 1700 later that day. They were working their third day after 3 days off.

Fatigue

The pilot reported waking at 0400 that morning after about 5.5 hours of sleep, and about 11 hours of sleep in the previous 48 hours. The pilot had been awake for about 5 hours prior to the occurrence. Usually, they would be asleep by 2200 for this sort of work schedule, but they reported that on that night they struggled to fall asleep until about 2230.

The pilot reported their mental fatigue at the time as ‘a little tired, less than fresh’, and that while they had packed a banana and muesli bar to eat that morning during their shift, they had left them behind. They reported having had their last meal around 1700 the day before.

Previous similar occurrences

There have been 62 runway excursions in the last 4 years at ALAs across Australia. 11 of these occurrences resulted in 14 injuries: 9 minor injuries to crew, 1 serious injury to a passenger and 4 minor injuries to passengers. Of these, 2 occurrences were at the Abrolhos Islands.

The ATSB investigated 6 of these 11 occurrences.

Safety analysis

It was considered unlikely that the braking capacity of the aircraft was affected by the seating configuration or low hydraulic fluid in the brake master cylinder. There were skid marks along the runway surface where the brakes had been applied and locked the wheels. While this indicates that full brake application was available, the locked wheels would have provided less stopping effectiveness than if the braking had been modulated to remain on the threshold of locking and the flaps retracted on touchdown. These elements, in combination with the long landing and groundspeed detailed above, meant that the pilot was unable to stop the aircraft before it entered the water.

There were opportunities to conduct a go-around prior to landing and during touchdown. The pilot recalled considering a go-around as they pushed the nose down to intercept the approach profile and the speed increased more than expected, however they advised that they expected to regain the correct profile and airspeed prior to landing. They also considered conducting a go‑around as the wheels made contact with the runway. However, having assessed that the airspeed was below the take-off speed of 70 kt, they were concerned that there was a risk of stalling over the water.

Fatigue is a known factor that can impair decision making and reduce reaction time. There was evidence that the pilot was possibly experiencing mild to moderate acute fatigue at the time of the occurrence. This was due to a combination of some restricted sleep in the previous 24 and 48 hours, and lack of sustenance that morning. However, it is difficult to conclude whether fatigue impaired the pilot’s actions in response to identifying the unstable approach and electing not to conduct a go-around. The ATSB reviewed the operators’ procedures for sleep arrangements during split shift duty periods and found that sign-on and sign-off times accounted for commuting time and aircraft preparation between scheduled departures.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the runway excursion, involving GippsAero GA8 registered VH-TBU, that occurred at Rat Island, Western Australia on 6 April 2023.

Contributing factors

- The aircraft was unstable during the approach and landed approximately halfway down the runway with insufficient remaining runway to stop.

- The pilot did not conduct a go-around, as required by the operator, when they identified the aircraft was not stabilised during the latter stages of the approach.

Other findings

- The pilot was possibly experiencing fatigue at a level known to affect human performance, due to a combination of restricted sleep and insufficient sustenance.

Safety actions

Safety action by Shine Aviation Services

- implemented late stage go-around training for pilots operating to the Abrolhos Islands

- implemented an increased oversight program for junior pilots and reviewed the non-technical skills syllabus

- amended training packages to clarify the aircraft flap retraction policy upon landing

- implemented anti-skid training into an appropriate location within training material

- included aircraft performance items into the line training syllabus for their single‑ and multi‑engine aircraft

- reviewed average pilot commuting times to improve the scheduling of rest periods and sleep periods for split duty times

- improved operational procedures to clearly define minimum turnaround times, minimum sign‑on and sign-off times

- reviewed the aircraft performance manual to ensure referenced material was up to date

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the pilot of the accident flight.

- a passenger of the accident flight.

- video footage of the accident flight and other photographs and videos taken on the day of the accident.

- recorded data on the aircraft.

- Shine Aviation Services.

- Bureau of Meteorology (BOM).

References

Gippsland Aeronautics (2019). GA8 Flight Manual. CASA Amendment 54. C01-01-03

Gunston, B. (2004). The Cambridge aerospace dictionary. Cambridge University Press.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- the pilot

- Shine Aviation Services

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- United States National Transportation Safety Board

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Runway number: the number represents the magnetic heading of the runway.

[2] This was the full flap setting required for the GA8 to achieve the factored landing roll required for Rat Island at the maximum landing weight of 1,814 kg.

[3] Go-around: A standard aircraft manoeuvre that discontinues an approach to landing.

[4] The manufacturer was previously known as Gippsland Aeronautics.

[5] Compressibility within the braking system requiring greater‑than‑expected pedal application to achieve effective braking.

[6] Vref: the reference landing approach speed. For the GA8 at idle power and full flap this was 70 kt.

[7] Flight Duty Period (FDP): A period of time that starts when a person is required, by an operator, to report for a duty period in which they undertake one or more flights as part of an operating crew and ends at the later of either the person’s completion of all duties associated with the flight, or the last of the flights; or 15 minutes after the end of the person’s flight, or the last of the flights.