Introduction

Despite continued concerted efforts to prevent collisions at level crossings by local, state and federal governments in conjunction with the rail industry, the ATSB continues to investigate similar occurrences.

Over the past decade the Bureau has conducted 17 investigations and one safety study.

The following investigations highlight some key learnings for both road users and rail infrastructure managers to help reduce collisions at level crossings.

Expectation bias

A truck driver who failed to stop before a passive level crossing collision in southern Queensland was probably influenced by expectation bias, having likely never seen a train at the crossing in the past.

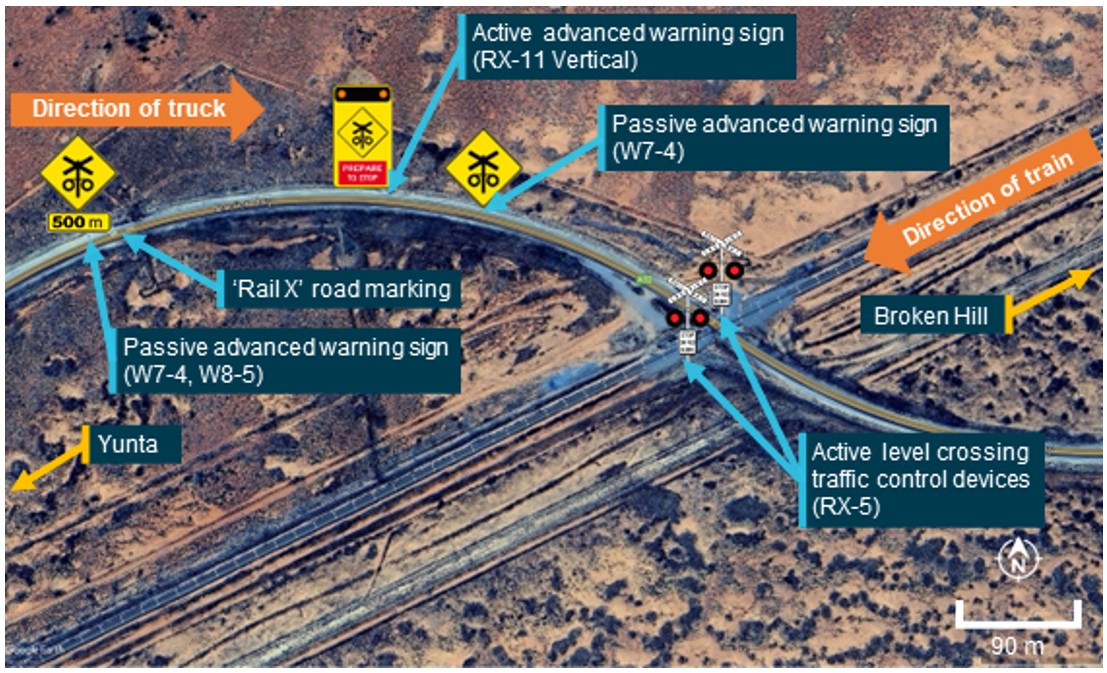

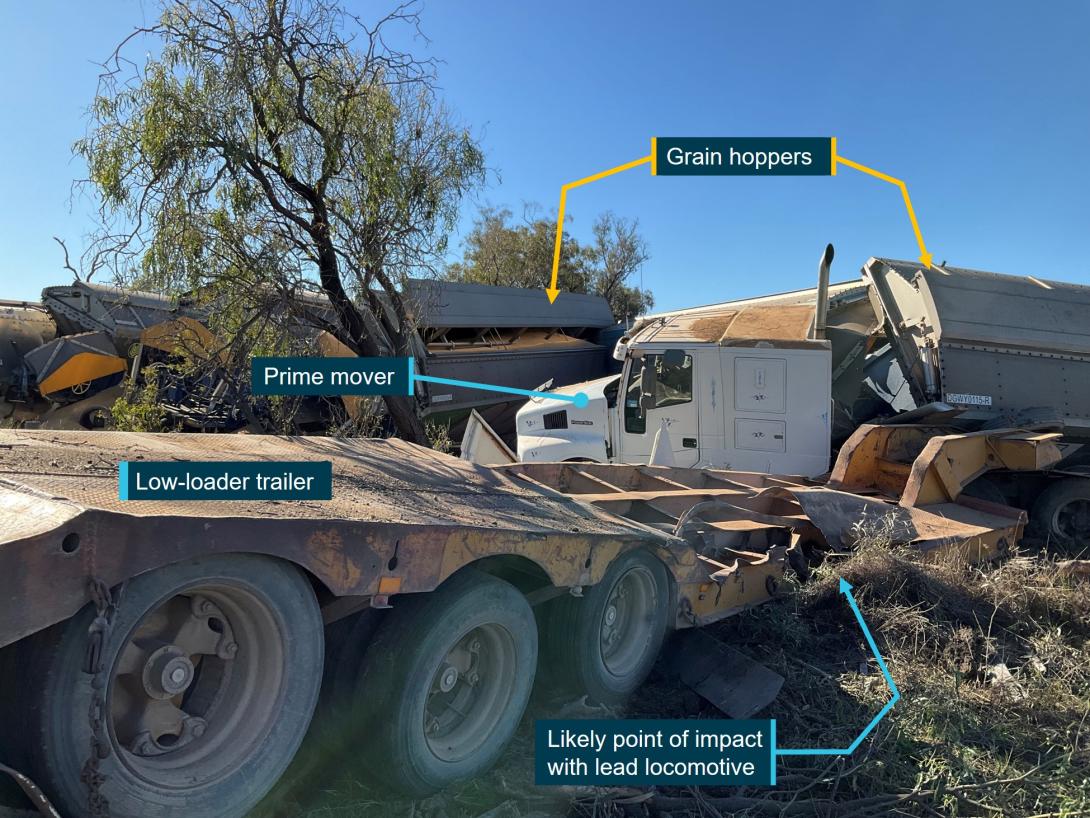

On 23 May 2024, a prime mover hauling a skid steer was about 50 metres north of Gooray Road level crossing, near Goondiwindi, when the truck driver saw a train approaching from the west. Assessing they could not stop in time, the truck driver accelerated, but the truck was unable to clear the crossing before the train collided with the truck’s trailer.

The truck driver and two train drivers were seriously injured in the collision, which also destroyed the train’s two locomotives and 12 grain hoppers, and the truck’s prime mover and low-load trailer.

Due to the infrequency of trains on that corridor, it is likely the truck driver had not seen a train at that crossing in the past. This created an expectation bias which probably reduced the effectiveness of the truck driver’s scan while approaching the crossing. Nonetheless, the signage instructed the driver to stop at the crossing, and the driver did not comply with this requirement.

This accident demonstrates the limitations of passive controls at level crossings, where the onus is on road users to follow these controls – making them particularly vulnerable to unintentional driver error, or intentional driver decisions.

Passive controls are common at level crossings where road and rail traffic volumes are low, and it is unlikely most road users will encounter a train at such a crossing. As road users become familiar with a level crossing where they have not previously encountered trains, they can unconsciously form an expectation that no trains will be present every time they approach that crossing.

It is therefore crucial that road users remain cognisant of the potential presence of trains at every level crossing, and are mindful of the consequences of a collision such as this one.

Passive controls cannot physically prevent vehicles from entering a crossing, and the onus is on road users to follow these controls. This makes passive level crossings particularly vulnerable to driver error (unintentional) or driver decisions (intentional), which can place road users at imminent risk of collision with rail traffic.

This incident also highlights, for truck drivers, the importance of completing preparatory checks and rectifying any problems which may be observed prior to moving their vehicle, as there is a significant risk of harm and damage when driving vehicles with mechanical issues.

Unfamiliar territory in a noisy environment

A motorist was fatally injured in a collision with a passenger train at the Kianawah Road level crossing, near Lindum Station in Wynnum West, Queensland after they passed through a gap between the end of the lowered boom barrier and a median island.

On the afternoon of 26 February 2021, a Queensland Rail suburban express passenger train was approaching the Kianawah Road level crossing in the Brisbane suburb of Wynnum West, Queensland. The boom barriers were in the lowered position and other protection devices (flashing lights) were active at the level crossing.

At the same time, after stopping to give way to opposing road traffic at the intersection, immediately adjacent to the level crossing, a motor vehicle turned towards the crossing. It then continued through the level crossing, bypassing the lowered boom barrier, colliding with the train. The motor vehicle was destroyed, and the sole occupant was fatally injured. The only 2 occupants of the train, the driver and guard, were not injured.

Our investigation found that there was a 3.1 m gap between the end of the boom barrier and the median island, which meant that the barrier only partially blocked road traffic that approached the level crossing from Lindum Road. In this instance, it was very likely that the driver of the motor vehicle followed the turn line markings on the road surface, which directed them past the end of the lowered boom barrier onto the level crossing and into the path of the approaching train. Safety concerns raised by local road users and work undertaken by the Government also indicated that the road-rail interface at the Kianawah Road level crossing was complex and visually noisy from a road user’s perspective.

Queensland Rail had not been managing risk at level crossings in accordance with the requirements of its level crossing safety standard. In particular, the standard stated that public and pedestrian level crossings were to be assessed every 5 years or sooner. However, the Kianawah Road level crossing had not been assessed for 19 years. Some other level crossings with high instances of incidents and accidents had also not been assessed for 20 years.

It was also identified that, between 2016 and 2021, Queensland Rail had just one person qualified to assess all their public, pedestrian, private, maintenance, and construction level crossings, which numbered in the thousands. Of the 1,138 public level crossings that required assessment within the 5-year timeframe, just 52 were completed.

Further, Queensland Rail and the Brisbane City Council did not have a formal road-rail interface agreement in place at the time of the accident, although negotiations were ongoing. This was a missed opportunity to collectively identify any unique risks associated with the level crossing and manage and maintain those risks through an agreed process.

Following the accident at the Kianawah Road level crossing, Queensland Rail and the Brisbane City Council have formalised an interface agreement encompassing all level crossings where they have a shared responsibility. In addition, Queensland Rail:

- Has installed a new boom barrier at the level crossing, compliant with the Australian Standard (1742.7), that fully protects road users when approaching the active crossing from Lindum Road. In addition, rectified a safety issue where the boom barrier did not fully comply with the requirements of the Australian Standard at 29 other level crossings within its jurisdiction.

- Assessed the Kianawah Road level crossing in accordance with the Australian Level Crossing Assessment Model (ALCAM) to establish a current assessment risk score rating.

-

Has trained 4 internal staff to undertake ALCAM assessments and introduced a procurement process to engage a contract firm to update outstanding regional ALCAM assessments over the next 5 years.

Level crossings are a complex environment and are well known for their high-risk consequences. While the ultimate preference is to avoid or remove level crossings, this is often very costly and not a practical solution. Therefore, it is important that road authorities and rail infrastructure managers collectively manage these risks. To achieve this, they should enter into an interface agreement as soon as possible to identify and manage hazards and risks at the road and rail interface, so far as is reasonably practicable.

Acute angles

Sighting from road vehicles can be severely restricted at passively protected level crossings with an acute angle road-to-track interface.

On 13 July 2016, a Warrnambool-bound V/Line passenger train collided with a semi-trailer at the Phalps Road passive level crossing at Larpent, near Colac, Victoria.

When the truck initially stopped at the crossing, the train was more than 300 metres away. The truck commenced moving towards the track when the train was between 220 and 260 m from the crossing. Unaware of the train approaching beyond their line of sight, the truck driver entered the level crossing and heard the train’s horn shortly before the locomotive struck the truck’s semi-trailer.

After impact, the train’s locomotive and all passenger cars derailed. The locomotive driver, train conductor, 18 passengers and the truck driver were injured. There were no fatalities.

The investigation, conducted by Victoria's Chief Investigator, Transport Safety, on behalf of the ATSB, found the driver was unable to detect the approaching train on the left due to the restricted view from the level crossing’s acute road-to-rail angle and the composition of the truck’s passenger-side window.

The ability of a truck driver to see along a railway track to their left can be affected by in-cab obstructions. The Australian Design Standard for passively controlled level crossings accounts for this possibility by requiring a viewing angle of no more 110 degrees for a driver looking to their left from the straight-ahead direction. If this viewing angel is exceeded, passive level crossing controls should not be used.

The investigation found that for a vehicle stopped at the northern side of the Phalps Road level crossing, the viewing angle to achieve the required sighting distance was 116 degrees. The Phalps Road level crossing was subsequently upgraded to active protection controls in August 2016.

Rail infrastructure and road managers should ensure that risk assessment processes take account available risk controls for hazards stemming from poor sighting at acute-angle level crossings and actively pursue their implementation.

Road users should be particularly cautious at passively-controlled acute-angle level crossings where their vision to the left may be affected by the road vehicle cabin design.

Conclusion

Each year, people continue to lose their lives or are injured at Australia's level crossings causing significant social and economic impacts on individuals, communities and businesses.

Record investment in rail and road infrastructure, combined with growing passenger traffic and freight demand, is continuing to increase interactions at level crossings.

Our investigations have identified there is a higher rate of collisions at passive level crossing, with a large proportion of these collisions involving heavy vehicles.

Passive controls cannot physically prevent vehicles from entering a crossing, and the onus is on road users to follow these controls. This makes passive level crossings particularly vulnerable to driver error (unintentional) or driver decisions (intentional), which can place road users at imminent risk of collision with rail traffic.